Introduction to Emergency General Surgery: Evaluation of the Acute Abdomen

Grace S. Rozycki

David V. Feliciano

Over the past several years, the acute care surgeon has emerged as the surgeon who provides care for patients whose lives are immediately threatened by surgical disease. These patients may present at any time of day or night, include almost any age, have the potential for complex medical histories, may deteriorate quickly, have minimal opportunity for preoperative work up, and therefore, are more prone to complications. Emergency general surgery covers a wide range of diseases. The acute abdomen includes many time-dependent diseases for which the principles of rapid assessment, diagnosis and treatment will lead to optimal outcomes. When assessing the patient with a potential acute abdominal condition, it is key to gather a focused history and physical examination, order the targeted tests and radiologic examinations, and then make a presumptive diagnosis or plan. If the diagnosis can be made with reasonable certainty, the second critical decision is to decide if an operation is indicated and, if so, then the third decision is optimal timing of the operation. If an obvious diagnosis cannot be reached through the usual mechanisms, then an alternative goal is to choose extended observation or to perform an emergent operation.

Pain

The visceral layer of the peritoneum is supplied by autonomic nerves, whereas the parietal peritoneum is supplied by somatic innervation from the spinal cord. Consequently, as pain fibers enter the spinal cord ipsilaterally, the pain localizes to that side versus that of visceral pain which is perceived to arise in the midline because sensory input enters the spinal cord bilaterally. Visceral pain is dull or crampy while parietal pain is sharp and usually persistent. Referred pain is felt at a site different from its origin and is sharp and persistent. An example is right shoulder pain from right-sided residual pneumoperitoneum. The complexity of pain is illustrated with appendicitis as the pain is initially poorly localized in the periumbilical area and, as the inflammatory process progresses, the irritation of the parietal peritoneum results in a change in the character of the pain to be sharper and more localized to the right lower quadrant of the abdomen.

History

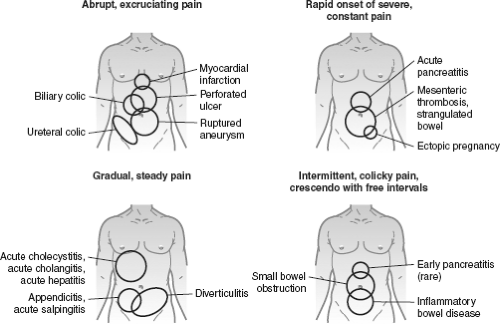

The etiologies of acute abdominal pain stem from intraperitoneal or extraperitoneal processes and include esophageal, gastrointestinal, vascular, gynecologic, urologic, and non-abdominal causes. The history should focus on the onset, character, location of the pain, prior symptoms, associated illnesses including medications, and previous abdominal surgery. A characterization of the onset and character of the pain is critical to help narrow the differential diagnosis. For example, if the patient recalls almost precisely when sudden and severe abdominal pain occurred, it is often due to a perforated hollow viscus or mesenteric ischemia. A more gradual onset of pain is more likely to occur with inflammatory conditions (pancreatitis, appendicitis, colitis) or a bowel obstruction.

The location of the abdominal pain may also narrow the differential diagnosis. Figure 43-1 shows the location of pain by abdominal quadrant for some common diseases. Localizing the pain to a specific area often helps to limit the differential and to determine what, if any, investigational studies need to be performed. The localization of abdominal pain by quadrant is not a precise indicator as the pain may be diffuse, occur in adjacent quadrants, or change location as the disease progresses. Of note, acute abdominal gynecologic

problems (including ectopic pregnancy) usually cause pain in the lower quadrants, while pneumonia and myocardial infarction may be associated with pain in the upper quadrants (Table 43-1).

problems (including ectopic pregnancy) usually cause pain in the lower quadrants, while pneumonia and myocardial infarction may be associated with pain in the upper quadrants (Table 43-1).

Figure 43-1. The location and character of pain are helpful in the differential diagnosis of the acute abdomen. |

Table 43-1 Causes of Abdominal Pain | |

|---|---|

|

For the immunocompromised patient, the differential diagnosis of acute abdominal pain is similar to that for the immunocompetent patient, but also includes infectious processes (especially cytomegalovirus and Epstein–Barr viruses), neutropenic enterocolitis, and bowel perforation secondary to lymphoma, CMV, sarcoma, mycobacteria, or pseudomembranous colitis.

Physical Examination

Inspection of the patient may yield important information to support a diagnosis. For example, jaundice may indicate hepatobiliary disease, restlessness may indicate colic (renal, hepatobiliary) and resistance to mobility may be consistent with peritonitis. The vital signs yield important information about the patient’s response to the disease process; for example, hypotension, fever, and tachycardia are consistent with dehydration or possible septic shock, often compensated but still dangerous.

A well-organized and systematic approach to the abdominal examination decreases the likelihood of omitting important steps or making a premature diagnosis. To differentiate tense muscles in the abdominal wall from peritonitis, ask the patient to bend their knees and place a pillow underneath them. Before beginning the examination, review with the patient the initial location of the abdominal pain and ask the patient to point to the area of maximal pain. Standing at the patient’s right side, the abdominal examination consists of the following steps:

Inspect for distension, pulsations, bulges, masses, discolorations, hematomas, or previous scars. A flank hematoma (Grey Turner’s sign) or periumbilical hematoma (Cullen’s sign) may indicate a retroperitoneal or intraperitoneal hematoma, respectively. Included in this step is the observation of respiratory movement including the use of the abdominal wall muscles.

Auscultate for the presence and character of bowel sounds or bruits. The presence of active, high-pitched bowel sounds may indicate a mechanical small bowel obstruction.

Percuss and palpate the abdomen to elicit signs of tenderness, peritonitis, and organomegaly. Percussion can be used to determine the presence of peritonitis, ascites, distended bowel, or hepatomegaly. Palpation should start from the opposite quadrant of maximal pain. Rebound tenderness is elicited when the examiner’s hands are quickly released from the patient’s abdomen. The information obtained with this maneuver is usually similar to that obtained from deep palpation, and, therefore, does not add much to the results of the physical examination. Figure 43-1 shows some common signs on abdominal examination that are relevant to the evaluation of the patient with an acute surgical abdomen.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree