103 Intracranial Hemorrhages

• “Head bleed” is an oversimplified term for intracranial hemorrhage because different types of hemorrhages have different causes, signs and symptoms, diagnostic strategies, and therapies.

• Descriptions of intracranial hemorrhage should include the anatomic location, estimation of size, presence of midline shift, and whether the hemorrhage is thought to be spontaneous or secondary to another process.

• Treatment recommendations regarding blood pressure management and anticonvulsant therapy remain controversial and lack strong evidence-based support.

Pathophysiology

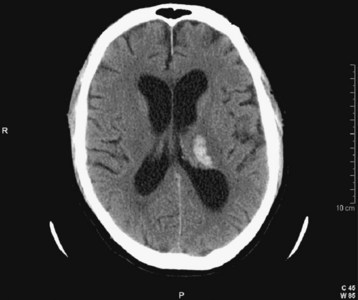

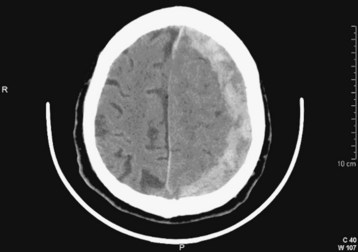

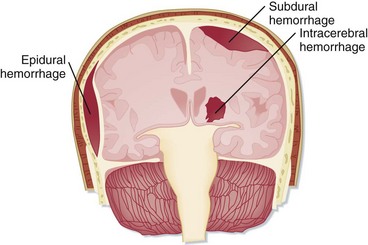

intracranial hemorrhage is the umbrella term used to encompass the many types of bleeding within the cranial vault (Figs. 103.1 to 103.5 and Table 103.1). Intraparenchymal hemorrhage implies blood within the substance of the brain. When the hemorrhage is not clearly secondary to a detectable cause, it is deemed a spontaneous hemorrhage. This term is often used synonymously with the terms hypertensive hemorrhage and, when anatomically appropriate, intracerebral hemorrhage. Intraparenchymal hemorrhages may also occur in the brainstem or cerebellum. SAH literally describes blood in the subarachnoid space, and if nontraumatic, a vascular lesion such as an aneurysm is the implied cause of the bleeding. SAH and intraparenchymal hemorrhage may coexist. Intraventricular hemorrhage means that blood is visualized within the ventricles by cranial CT, and it is most often present with other types of intracranial hemorrhage. intracranial hemorrhages outside the brain substance are referred to as extraaxial hemorrhages and include both subdural hemorrhages and epidural hemorrhages. Although uncommon exceptions exist, extraaxial hemorrhages almost always have a traumatic etiology. The term hemorrhagic stroke might literally describe abrupt symptoms with any of the previously mentioned hemorrhages, but it is sometimes used in a more restrictive sense to describe hemorrhagic changes in an area of ischemic stroke to the point of being visible on cranial CT; this is termed hemorrhagic transformation of ischemic stroke.

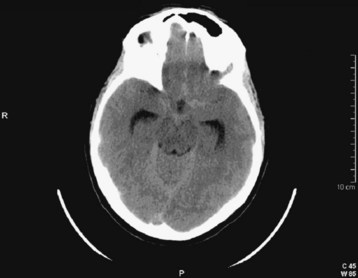

Fig. 103.2 Computed tomography scan: acute subarachnoid hemorrhage.

Blood density is not as dramatic as in Figure 103.13. Hydrocephalus with enlarged temporal horns of the lateral ventricle is present.

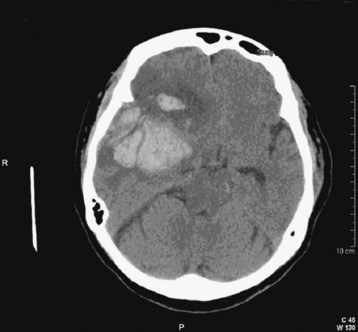

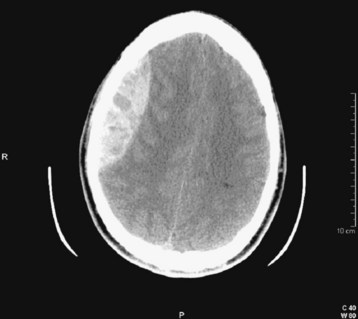

Fig. 103.4 Computed tomography (CT) scan: acute epidural hematoma with the “swirl” sign.

This is a slice from a repeated CT scan of the patient in Figure 103.10 taken approximately 1 hour later. The marbled density of the clot is consistent with ongoing hemorrhage. Note the lens shape of the hematoma.

See Table 103.1, Types of Intracranial Hemorrhage, online at www.expertconsult.com

Table 103.1 Types of Intracranial Hemorrhage

| TYPE OF HEMORRHAGE | CORRESPONDING FIGURES IN TEXT | FINDINGS IN FIGURES |

|---|---|---|

| Intraparenchymal (synonyms: intracerebral, lobar, hypertensive) | Fig. 103.1 | Blood within the substance of the brain; thalamic hemorrhage |

| Subarachnoid | Fig. 103.2 | Acute hemorrhage with blood in the subarachnoid spaces |

| Subdural | Fig. 103.3 | Blood external to the brain; crescent-shaped hemorrhage |

| Epidural | Fig. 103.4 | Blood external to the brain; lens-shaped hemorrhage |

| Hemorrhagic transformation of ischemic stroke | Fig. 103.5 | Hemorrhage within a wedge-shaped area of ischemia |

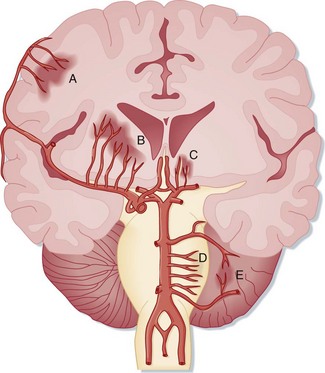

Spontaneous intraparenchymal hemorrhages (e.g., intracerebral hemorrhages, lobar hemorrhages, hypertensive hemorrhages) are most often associated with chronic hypertension. Cerebral amyloid angiopathy is increasingly being recognized as a contributing process in the elderly. Chronic excessive alcohol use is also a risk factor. Hemorrhage usually originates from rupture of small penetrating branch arteries of the vessels at the base of the brain1 (Fig. 103.6).

Serial cranial CT demonstrates that many intracerebral hemorrhages expand over the course of several hours.2 The initial hemorrhage may infiltrate the white matter with little direct destruction, but continued hematoma expansion, white matter edema, additional hemorrhage from surrounding vessels, and the development of hydrocephalus may all contribute to increased ICP and secondary neuronal injury. The frequency of anticoagulant-associated intracerebral hemorrhage is increasing.3 Warfarin therapy does not appear to increase hematoma volume initially, but it does increase the risk for later hematoma expansion.4

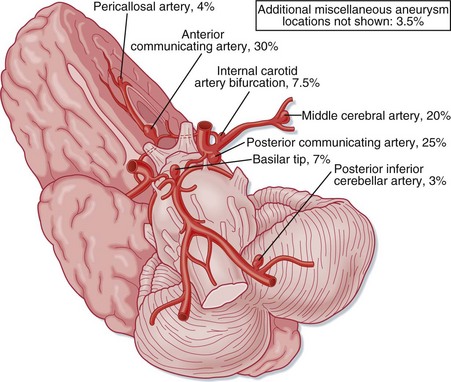

SAH literally means “blood in the subarachnoid space.” Trauma is the most common cause. Spontaneous, or nontraumatic, SAH has an entirely different differential diagnosis. About 80% of spontaneous SAHs are caused by rupture of saccular (berry) aneurysms of the intracranial vessels, which are commonly located near intracranial arterial bifurcations of the circle of Willis5,6 (Fig. 103.7). Aneurysms are often named after the vascular site of origin, such as the anterior communicating artery or middle cerebral artery. Aneurysms that develop following vascular infection from endocarditis are termed mycotic aneurysms. Some aneurysms also cause symptoms without rupture from a mass effect or from emboli originating within the aneurysm. Rupture of an intracranial aneurysm abruptly raises ICP and leads to the onset of symptoms. The bleeding may be confined to the subarachnoid space, or a hematoma may extend into the brain substance and create an intraparenchymal hemorrhage, which in turn may rupture into the ventricles. Vasospasm of the vascular tree related to the aneurysm typically takes hours to develop and may worsen regional ischemia.

Fig. 103.7 The intracranial vasculature showing the most frequent locations of intracranial aneurysms.

Arteriovenous malformations are another cause of intracranial hemorrhage of both the subarachnoid and intraparenchymal anatomic subtypes. These arteriovenous shunts vary in their anatomy, and many patients have saccular aneurysms as well. Lesions with deep venous drainage and high pressure in the feeding vessels are at increased risk for bleeding.7 Cavernous angiomas are low-pressure vascular lesions associated with small hemorrhages.

The anatomic terminology regarding intracranial hemorrhage historically comes from postmortem neuropathology descriptions. In the ED, intracranial hemorrhages are most often diagnosed by cranial CT, which remains the initial diagnostic modality of choice. The appearance of acute hemorrhage usually contrasts vividly with that of the other intracranial contents. The types of intracranial hemorrhage are anatomically classified primarily by their relationship to the substance of the brain and the meninges.8 Simplistically, hemorrhages may be thought to be located in the brain substance (intraparenchymal, intracerebral), within the ventricles (intraventricular), in the subarachnoid space between the meninges and the brain, or outside the brain and meninges (subdural, epidural) (Figs. 103.8 and 103.9).