92 Inotropic Therapy

Rationale for Using Inotropic Therapy in the Critically Ill

Rationale for Using Inotropic Therapy in the Critically Ill

Use of Inotropes for Reversing Impaired Myocardial Contractility

The first category of situations where inotropic therapy is generally considered includes cardiogenic shock, acute heart failure, or acute exacerbation of chronic heart failure. However, although the use of such therapy in these clinical conditions seems logical on a purely pathophysiologic basis, no demonstration of a beneficial impact on morbidity and mortality can be found in the literature. Moreover, almost all the commercially available inotropes have been shown to be associated with increased mortality rates when given on a long-term basis to patients with chronic heart failure. It has been postulated that the long-term use of inotropes may lead to deterioration of left ventricular function through acceleration of myocardial cell apoptosis.1 Additionally, the beneficial effects on mortality of agents known to have negative inotropic effects, such as β-blockers, is now well established in patients with chronic heart failure.2,3 Therefore, inotropic therapy is generally reserved for patients with cardiogenic shock or for patients with advanced heart failure whose condition is refractory to standard therapy including diuretics, digoxin, β-blockers and angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors. Under these conditions, clinicians can expect short-term positive effects of intravenous (IV) inotropic therapy, allowing cardiovascular stabilization. In patients with refractory heart failure who are candidates for cardiac transplantation, this therapy can be used as a bridge to transplantation. In those with potentially reversible causes of acute heart failure (such as myocardial infarction or acute myocarditis), short-term inotropic therapy must be considered as an appropriate bridge to coronary revascularization or recovery. The development of bedside echocardiography in the intensive care unit (ICU) should allow appropriate use of inotropic therapy, since this method provides a more accurate assessment of systolic cardiac function than traditional invasive methods like pulmonary artery catheterization.

Use of Inotropes for Achieving Supranormal Levels of Oxygen Delivery

High-Risk Surgical Patients

The concept of attempting to achieve supranormal hemodynamic endpoints emerged from studies in high-risk surgical patients. In a prospective study in high-risk patients undergoing surgery, Shoemaker et al. showed that the use of supranormal hemodynamic values as therapeutic endpoints was associated with a reduction in mortality from 33% to 4%.4 In the protocol group, dobutamine and dopamine were given as inotropic drugs—even in the absence of evidence of reduced cardiac contractility—when volume resuscitation (and packed red blood cells if necessary) failed to achieve supranormal values of myocardial oxygen delivery (DO2)4 (DO2 > 600 mL/min/m2). In other randomized studies performed in high-risk patients undergoing surgery, the deliberate perioperative increase in DO2 above supranormal values using fluid infusion and various inotropic drugs (dobutamine, dopamine, epinephrine, dopexamine) were associated with decreased mortality and postoperative complications.5 It remains unclear, however, whether the benefits were related to the increased DO2 per se or to other antiinflammatory effects of catecholamines.6 The issue of drug dose is also essential. A recent meta-analysis has suggested that in the setting of major surgery, dopexamine at low doses but not at high doses could improve outcome.7 From all these findings, it is reasonable to consider the increase of cardiac output and DO2 towards supranormal values during the perioperative period in high-risk patients undergoing elective major surgery.

Critically Ill Patients

Whether this therapeutic approach could also be applied to patients admitted to the ICU for established acute illnesses has been a matter of debate. On the one hand, a pathologic myocardial oxygen consumption/oxygen delivery (VO2/DO2) dependency, presumably due to impaired oxygen extraction capabilities, has been reported in various categories of acute illnesses such as sepsis8 and acute respiratory distress syndrome.9 Such a phenomenon was reported to correlate with the presence of increased blood lactate, a marker of global tissue hypoxia,8 and to be associated with a poor outcome.10 This so-called pathologic oxygen consumption/supply dependency would incite the clinician to increase DO2 towards supranormal values to overpass its critical level. However, such an aggressive therapeutic approach has been seriously questioned since the publication of randomized clinical trials performed in patients with acute illnesses that did not demonstrate any benefit from deliberate manipulation of hemodynamic variables toward values higher than physiologic values.11,12 In one of these studies, the mortality rate was even higher in the group of patients assigned to receive an aggressive treatment aimed at achieving supranormal values of DO2.11 It was postulated that deleterious consequences of the use of high doses of dobutamine in patients of the protocol group were responsible for the increased mortality. It has to be noted that (1) the patients of the protocol group received high doses of the inotropic agent despite the absence of evidence for an altered contractility, and (2) in most of these patients, the aggressive inotropic support failed to achieve the target value of VO2 (170 mL/min/m2). The analysis of the subgroup of septic patients of this study showed that the survivors were characterized by ability to increase both DO2 and VO2 regardless of their group of randomization.13 The non-survivors were characterized by an inability to increase their VO2 despite the increase in DO2, suggesting a more marked impairment of peripheral oxygen extraction in non-survivors than in survivors.13 In addition, the ability to increase cardiac output and DO2 was also significantly reduced in non-survivors in comparison with survivors, suggesting a decrease in cardiac reserve in those patients who will die.13 This is not a surprising finding, since the degree of myocardial dysfunction in septic shock correlates with increased risk of death. In this regard, it has been suggested that the response to a dobutamine challenge could have a prognostic value in septic patients. Indeed, in two prospective studies, survivors were able to increase both VO2 and DO2 in response to dobutamine, while non-survivors were unable to increase either DO2 or VO2 or both.14,15

From all the results of randomized controlled studies, the deliberative attempt to achieve supranormal hemodynamic targets in the general population of critically ill patients is no longer recommended.16,17 However, in the early phase of septic shock when blood flow and DO2 are generally low, an aggressive hemodynamic therapy including inotropes, aimed at rapidly normalizing DO2, was demonstrated to result in a better outcome in a randomized control trial.18 Thus, in the early phase of septic shock and maybe in other acute illnesses, it could be essential to rapidly restore normal global blood flow to avoid further deleterious consequences of systemic hypoperfusion. In later stages of the disease, with inflammatory processes and organ dysfunction already developed, no evidence of benefit from a further increase in DO2 has been shown. However, it seems likely that cardiac output should be kept in the normal range by using volume and/or inotropes to prevent worsening of the insult.

Pharmacologic Properties of Inotropic Agents

Pharmacologic Properties of Inotropic Agents

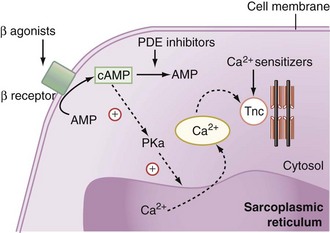

Adrenergic Signaling

Natural as well as synthetic catecholamines enhance the Ca2+ cytosolic amount, which is directly related to the force of contraction (Figure 92-1). Ca2+ fixes on the troponin C Ca2+-specific binding site, inducing a conformational change that leads to the fixation of the myosin head to the actin filament. Hydrolysis of the adenosine monophosphate (ATP) molecule located on the myosin head to adenosine diphosphate (ADP) simultaneously induces the flexion of the myosin neck and the shortening of the contractile apparatus.

β1-Adrenergic Receptors

Pharmacologic Properties of the Inotropic Agents Used in Clinical Practice

Phosphodiesterase Inhibitors

Despite the major role of catecholamines in the management of critically ill patients with inadequate cardiac output, problems such as tachycardia, arrhythmias, increased myocardial VO2, excessive vasoconstriction, or loss of effectiveness with prolonged exposure to β-agonists may occur. Thus, other inotropic drugs such as phosphodiesterase inhibitors (milrinone and enoximone) have been proposed for the management of myocardial dysfunction. These synthetic drugs inhibit the peak III isoform of phosphodiesterase, which catalyses cAMP (see Figure 92-1). By increasing intracellular cAMP concentration, they induce a potent vasodilation of arterial and venous systems through relaxation of vascular smooth muscle. The left ventricular preload is reduced to a greater extent than with dobutamine. At the cardiac level, phosphodiesterase inhibitors induce an inotropic effect similar to that induced by dobutamine. The heart rate is increased only at high rates of administration. The resulting effect is an increase in cardiac output. Because the enhancement of cAMP intracellular concentration also promotes the reuptake of Ca2+ by the sarcoplasmic reticulum, phosphodiesterase inhibitors facilitate ventricular relaxation. Finally, since β-agonists exert their action by increasing the production of cAMP, phosphodiesterase inhibition could enhance their adrenergic effects. This is the pharmacologic basis for the synergic association of β-agonists and phosphodiesterase inhibitors.

Calcium Sensitizers

Calcium sensitizers increase the sensitivity of troponin C for Ca2+ and hence the force and duration of the cardiomyocytes’ contraction (see Figure 92-1). To date, levosimendan is the only calcium sensitizer approved for clinical use. The advantage of levosimendan over classical inotropes would be to increase the force of contraction without enhancing the influx of Ca2+ into the cytosol and thus without increasing the risk of arrhythmias related to this ionic alteration. Some degree of phosphodiesterase III inhibitory activity probably also contributes to the inotropic effect of these drugs. It also induces vasodilation by opening ATP-dependent K+ channels.19

Cardiac Myosin Activators

Cardiac myosin activators belong to a new class of inotropes. They increase the activity of the ATPase of the myofibrils, increasing the contractile force of the cardiomyocytes without increasing the amount of ATP molecules required for contraction—that is, without increasing the myocardial VO2.20 Additionally, these substances increase the cardiac contractile force without the potentially deleterious increase in intracytoplasmic Ca2+ concentration. Cardiac myosin activators have been tested in animal studies in which their inotropic properties have been well demonstrated. Pharmacologic studies in humans are ongoing.

Istaroxime

Istaroxime is a new drug that inhibits the Na+/K+-ATPase, increasing the activity of the sarcoendoplasmic reticulum calcium ATPase pump. It induces some inotropic and lusitropic effects.21 In animals, istaroxime was demonstrated to decrease the end-diastolic volume of the left ventricle and to increase the left ventricular ejection fraction. In patients with decompensated heart failure without hypotension, istaroxime decreased the pulmonary artery occlusion pressure and improved the diastolic function of the left ventricle.22 This drug is still under clinical evaluation.

Hemodynamic Effects of Inotropic Agents in Critically Ill Patients

Hemodynamic Effects of Inotropic Agents in Critically Ill Patients

Effects on Cardiac Output

Dobutamine and Dopamine

In patients with acute heart failure, the effects of these two agents were compared in a crossover trial.26 Whereas dobutamine (2.5-10 µg/kg/min) increased cardiac output through an increase in stroke volume in a dose-response fashion, dopamine increased stroke volume and cardiac output at 4 µg/kg/min but not at higher doses, presumably because of an increase in left ventricular afterload. It was also reported that pulmonary artery occlusion pressure decreased with dobutamine while it increased with dopamine. Similar findings were observed in patients with respiratory failure in whom dopamine also increased the left ventricular end-diastolic volume measured using isotopes, while dobutamine did not.27 This suggests an increase in left ventricular preload only with dopamine.

In patients with septic shock, in addition to hypovolemia, severe systemic vasodilation is associated with a variable degree of depressed myocardial contractility.28 Dopamine at median or high doses has been proposed as one of the first-line catecholamines when arterial pressure remains low despite adequate volume resuscitation,19 as it can exert both an α-mediated increase in arterial tone and a β-mediated increase in myocardial contractility. However, it was reported that restoration of an adequate MAP with dopamine was mainly produced by the increase of cardiac output through an increase in stroke volume and, to a lesser extent, increase in heart rate; whereas minimal effects on systemic vascular resistance (SVR) were observed despite relatively high doses of this agent.29 Dopamine was even demonstrated to increase cardiac output markedly while SVR fell in septic patients without shock.30 Conversely, in another study in patients with severe septic shock, cardiac output did not increase significantly with dopamine at doses up to 25 µg/kg/min while SVR either did not change or significantly increased.31 This emphasizes the great heterogeneity in the response to dopamine among septic patients and hence the difficulty to predict clinical hemodynamic effects from pharmacologic properties because of interindividual differences in terms of severity of the insult, underlying diseases, comorbidities, integrity of the neurovegetative status, drugs concomitantly prescribed, and other factors.

In patients with septic shock and depressed myocardial function, dobutamine is expected to increase stroke volume and heart rate owing to its β1-adrenergic properties but a vasodilatory effect owing to its β2-adrenergic properties. Accordingly, an increase in cardiac output and a decrease in SVR with dobutamine were reported in septic patients.32,33 This emphasizes the need to give a potent vasopressive agent to septic shock patients when dobutamine is administered to support cardiac function in the presence of depressed myocardial contractility. One potential advantage of dobutamine is the decrease in cardiac filling pressures that could allow an additional volume infusion to improve further cardiac output when necessary. A change from dopamine to dobutamine was shown to result in lower right and left ventricular filling pressures and an increase in right ventricular ejection fraction for the same pulmonary artery pressure and right ventricular end-diastolic volume suggesting that dobutamine can exert a more favorable effect on cardiac contractility than dopamine.34 This has justified the recommendation to give dobutamine rather than dopamine when use of an inotropic drug is judged necessary in patients with severe sepsis or septic shock.17 However, because of the alteration of the β-adrenergic pathway in the septic heart, the effect on stroke volume and cardiac output of a β-agonist agent such as dobutamine may be attenuated in septic patients in comparison with nonseptic patients. In this regard, infusion of dobutamine at 5 µg/kg/min, a dose able to increase cardiac output substantially in patients with congestive heart failure,35 has been reported to exert variable effects in the context of sepsis. For example, dobutamine at 5 µg/kg/min was reported to induce a substantial increase in cardiac output in some studies in patients with severe sepsis32,36 and to have no significant effect on cardiac output in some studies investigating patients with septic shock.37–41 It is likely that these differences in response to dobutamine were related to various individual factors, including differences in the vasopressor treatment coadministered, in the degree of myocardial depression and/or β-receptor down-regulation. In this regard, Silverman and associates showed that incremental doses of dobutamine (0, 5, 10 µg/kg/min) produced a dose-related increase in cardiac output in septic patients without shock but no positive effect on cardiac output in patients with septic shock, even for the highest dose.23 Interestingly, they also found that post-β-adrenergic receptor signal transmission was impaired only in patients of the septic shock group and that impairment of β-adrenergic receptor responsiveness found in both groups was significantly more marked in the septic shock group.23 These findings which allow the divergent results of numerous studies to be reconciled32,36–43 emphasize the unpredictability of the effects of β-agonist agents in patients with sepsis. It must be stressed that the absence of positive cardiac response to dobutamine seems a marker of poor outcome in septic shock patients.14,15,40 Because dobutamine also has potentially harmful effects (e.g., myocardial ischemia, cardiac arrhythmias), monitoring its effects on cardiac output to check its efficacy is the minimum required. However, no high-level recommendation on which method of cardiac output monitoring (e.g., pulmonary artery catheter, transesophageal Doppler, pulse contour method) is the more appropriate in this setting is currently available.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree