Infections

(See also septic shock,  p.118.)

p.118.)

p.118.)

p.118.)Systemic inflammation has a loose, clinical definition, the systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS), which can be caused by many diseases that result in admission to critical care. When the cause is infection sepsis may develop 25-30% of ICU admissions are initially associated with sepsis. Severe sepsis has a mortality of 40-50%.

Diagnostic criteria

Sepsis

Proven or suspected infection and 1 or more of:

Temperature >38°C or <36°C.1

Heart rate >90/minute.1

Altered mental status.

Hyperglycaemia (>7.7 mmol/L) in the absence of diabetes.

Significant oedema or positive fluid balance (>20 ml/kg in 24 hours).

Raised CRP or procalcitonin (>2 standard deviations).

Arterial hypotension (MAP <70 mmHg, systolic <90 mmHg, or a decrease in systolic >40 mmHg).

Urine output <0.5 ml/kg/hour despite fluid resuscitation.

Raised creatinine (↑ by >44.2 µmol/L).

Ileus (absent bowel sounds).

Serum bilirubin >70 µmol/L.

Lactate >1.6 mmol/L.

Mottling or ↑ capillary refill time.

Septic shock

Sepsis with associated hypotension, or hypoperfusion (e.g. oliguria) after adequate fluid resuscitation.

Severe sepsis

Sepsis with evidence of organ dysfunction:

Urine output <0.5 ml/kg/hour despite fluid resuscitation

Lactate >1.6 mmol/L

Platelet count <100 × 109/L, or INR >1.5.

Creatinine >177 µmol/L.

Serum bilirubin >34 µmol/L.

Causes

Causes of SIRS include: infection, trauma or burns, pancreatitis, infarction: myocardial, intracerebral, bowel, pulmonary embolism, drug and alcohol withdrawal, massive blood transfusion.

Infections causing sepsis may be community or hospital/health-care acquired (ICU acquired is a subset). Common sites of infection include:

Respiratory (˜38%).

Device related (˜5%).

Wound/soft tissue (˜9%).

Genitourinary (˜9%).

Abdominal (˜9%).

Endocarditis (˜1.5%).

CNS (˜1.5%).

The natural defences against infection may be disrupted by:

Trauma, burns, or major surgery (especially GI, GU surgery, or debridement of localized infections).

Intestinal obstruction/distension; gut ischaemia or perforation.

Endotracheal intubation or tracheostomy.

Indwelling intravascular catheters, urinary catheters and wound drains.

Intravenous infusions of fluids, drugs and nutrition.

In immunocompromised patients unusual, multiple or opportunistic infections (e.g. fungal) may be seen. Common causes of immunocompromise include:

Drug treatment: chemotherapy, steroids.

Haematopoietic stem cell transplants.

Radiation injury.

AIDS.

Malnutrition, alcohol/drug abuse, or prolonged systemic disorders (including renal failure, hepatic failure, malignancy, multiple infections).

Multiple trauma, major surgery, multiple blood transfusions.

Presentation and assessment

Presentation of infections, SIRS and sepsis varies according to infection site/type, and comorbidities. Non-localizing signs/symptoms include:

General: pyrexia (or hypothermia, particularly in the elderly or immunocompromised), sweats, rigors.

Respiratory: tachypnoea and hypoxia.

Cardiovascular: tachycardia (bradycardia may be a pre-terminal sign):

Peripheral vasodilatation (warm peripheries); or peripheral shut-down (cold peripheries) usually as late manifestation

↑cardiac output if monitored, (though it may decrease in severe sepsis) and ↓ systemic vascular resistance

Poor perfusion (metabolic acidosis, raised lactate)

Hypertension or hypotension/shock

Angina, or evidence of cardiac ischaemia

Peripheral/dependent oedema

Neurological: agitation, confusion, diminished consciousness, syncope.

Renal: oliguria, raised urea and creatinine.

GI: anorexia, nausea and vomiting.

Investigations

ABGs (metabolic acidosis, hypoxia).

Coagulation screen, including D-dimers and fibrinogen (DIC, D-dimers may also be raised in response to inflammation).

Serum calcium, magnesium, phosphate.

Serum glucose (hypo/hyperglycaemia).

ECG.

Some investigations may also confirm the likelihood of sepsis, or identify the source or type of organisms involved:

Serum procalcitonin (PCT; used in some centres to help differentiate inflammation from infection).

Serum (and urine) antigen or antibody tests may be available for some organisms, including:

Legionella and Pneumococcal antigens are routinely tested in urine

Mycoplasma

Protozoal or helminthic infections

Bacteriology, 1 or more of the following samples:

Septic screen: blood,1 urine, and sputum cultures

Wound swabs; drain fluid (wound, chest, or other drains)

Nose and throat swabs (for culture and/or viral PCR)

Stool (for culture or for toxin detection, e.g. C. difficile toxin)

If any invasive lines are removed, line-tips may be sent for culture

Some institutions take brush samples from CVCs

BAL samples (samples may be sent for bacterial, fungal, specialist culture or tests, e.g. AFBs for TB; viral PCR; immunofluorescence, galactomannan)

Samples of ‘tapped’ fluid (e.g. ascites, pleural fluid)

Speculum exam and vaginal swabs

Gram stains may be useful where rapid identification of any organism is significant (e.g. in CSF), or where unusual organisms are significant (e.g. gut organisms in pleural fluid); in other situations they do not aid diagnosis (e.g. Gram stain of BAL samples).

CXR (pneumonia, mediastinitis, perforated viscus).

US and/or CT scan of chest, abdomen (including renal and hepatic), head, or pelvis for evidence of a collection.

Differential diagnoses

Any non-infectious disease which causes an inflammatory response.

Infection from another site.

Immediate management

Airway: endotracheal intubation may be required.

Where infection or threatens airway patency.

Where there is ↓consciousness (GCS ≤8).

To facilitate mechanical ventilation.

Breathing: ensure breathing/ventilation is adequate.

Mechanical ventilation may optimize oxygenation in severe shock.

Respiratory infections may compromise breathing and require mechanical ventilation.

Circulation: support should be commenced in patients with hypotension or elevated serum lactate.

Large peripheral venous cannulae are required.

Arterial and/or central venous cannulation should be undertaken as soon as feasible, checking coagulation studies and platelets first.

Resuscitate with crystalloids/colloids, (in first 6 hours), aiming for:

MAP ≥65 mmHg

CVP 8-12 mmHg (12-15 mmHg if mechanically ventilated)

Urine output ≥0.5 ml/kg/hour

CVC oxygen saturations ≥70% (or mixed venous >65%)

If venous SaO2 not achieved consider:

Further fluid resuscitation or dobutamine up to 20 mcg/kg/minute

Measurement of CO (e.g. oesophageal Doppler, pulse contour analysis) and SVR estimation will allow assessment of the effects of fluids and the need for vasopressors.

Vasopressor therapy with noradrenaline 0.05-3 mcg/kg/minute or dopamine 0.5-10 mcg/kg/minute (via a central catheter) is indicated when fluid challenge fails to restore BP/organ perfusion.

Infection identification and control

Treat any identifiable underlying cause, make a full survey for likely sources of infection, take a focused clinical history, and review notes and charts where possible.

Take all appropriate cultures; ensure 1-2 percutaneous blood culture samples, also sample blood from each intravascular catheter

Commence appropriate antibiotics ideally within 1st hour of treatment: respiratory ( p.334), abdominal (

p.334), abdominal ( p.346), wound/soft tissue (

p.346), wound/soft tissue ( p.342), GU (

p.342), GU ( p.344), endocarditis (

p.344), endocarditis ( p.338), CNS (

p.338), CNS ( p.340).

p.340).

Remove intravascular access devices that are a potential infection source after establishing other vascular access.

Arrange surgery, if required, to remove focus of infection.

Further management

Admit the patient into suitable critical care facility.

Continue invasive monitoring of respiratory and circulatory status.

Infection

Use infection control procedures where resistant or highly infectious agents are suspected ( p.382).

p.382).

Report any notifiable diseases ( p.380).

p.380).

Reassess antimicrobial regimen within 72 hours and adjust according to culture results; following advice from microbiology, aim to de-escalate antimicrobial therapy from broad spectrum to targeted therapies:

Adjunctive therapies

Treat or prevent complications

Vasopressor resistant septic shock (VRSS) may occur, where hypotension and tissue hypoperfusion cannot be corrected with standard vasopressor/inotropic therapy; the following have been tried but have little evidence to support their routine usage:

Vasopressin infusion 0.01-0.04 units/minute IV infusion

Alternatively consider terlipressin 1 mg IV 8hourly

Methylene blue IV may improve haemodynamic status

Respiratory:

Use a weaning protocol where appropriate

Renal:

Do not use ‘renal dose’ dopamine

Correct severe metabolic acidosis; use continuous veno-venous haemofiltration (CVVH) or intermittent haemodialysis if necessary

Avoid bicarbonate therapy for lactic acidosis if pH ≥7.15

Haematology:

Do not use erythropoietin to treat sepsis-related anaemia

Use FFP/fibrinogen to correct clotting abnormalities if there is bleeding, or invasive procedures are planned

Minimize the use of blood products by following a restrictive transfusion policy for blood and for platelets (see pp.299 and 304)

pp.299 and 304)

Do not use antithrombin therapy

Other measures (see also p.10):

p.10):

Provide stress ulcer prophylaxis (e.g. ranitidine 50 mg IV TDS) if appropriate; unless contraindicated use DVT prophylaxis; maintain serum glucose <10 mmol/L (avoiding hypoglycaemia); use a sedation protocol and scoring system

Consider antipyretics and/or peripheral cooling for pyrexia; avoid hyperpyrexia (temperature >40°C)

Enteral nutrition may maintain integrity of gut mucosal barrier; PN may be required in some situations (e.g. small bowel damage)

Pitfalls/difficult situations

Cause/source of infection may not be clear, consider non-obvious locations (retro-peritoneal space, vertebrae).

The diagnosis of sepsis requires proven or suspected infection.

Examples of proven infection include: positive cultures, Gram stain or PCR; evidence of infection (e.g. pus) in an otherwise sterile area, such as peritoneum or CSF; CXR changes of pneumonia; evidence of bowel perforation; stigmata of meningococcal septicaemia.

Fungal infections are often overlooked, suspect it in cases of 2° infections, and in immunocompromised patients.

DIC may be difficult to treat, seek expert haematology advice.

Patients with impaired renal function (or on CVVH/IHD) may require alterations to medication doses, discuss with pharmacy.

Adapt antimicrobial regimens for patients with penicillin allergy.

Mixed pictures of shock often occur with sepsis coexisting with other causes such as cardiac failure.

Have a low threshold for suspecting vascular access catheters as a source for bacteraemia.

Organisms are often not found in culture (in up to 40% of cases).

1SIRS is the response to a variety of clinical insults resulting in with ≥2 of the first 4 signs.

1Blood cultures should be taken from every invasive line, as well as 1-2 percutaneous venous samples; percutaneous venous stabs should be taken from different sites to minimize the risk of skin contamination.

Further reading

Albert M, et al. Utility of Gram stain in the clinical management of suspected ventilator-associated pneumonia. Secondary analysis of a multicenter randomized trial. J Crit Care 2008; 23: 74-81.

Dellinger RP, et al. Surviving Sepsis Campaign: international guidelines for management of severe sepsis and septic shock. Intensive Care Med 2008; 34: 17-61.

Harrison DA, et al. The epidemiology of severe sepsis in England, Wales and Northern Ireland, 1996 to 2004: secondary analysis of a high quality clinical database, the ICNARC Case Mix Programme Database. Crit Care 2006; 10:R42 (doi:10.1186/cc4854).

Kumar A, et al. Duration of hypotension before initiation of effective antimicrobial therapy is the critical determinant of survival in human septic shock. Crit Care Med 2006; 34(6): 1589-96.

Kwok ESH, et al. Use of methylene blue in sepsis: a systematic review. J Intensive Care Med 2006; 21:359-63.

Otero RM, et al. Early goal-directed therapy in severe sepsis and septic shock revisited: concepts, controversies, and contemporary findings. Chest 2006; 130: 1579-95.

Rivers E, et al. Early goal directed therapy in the treatment of severe sepsis and septic shock. N Engl J Med 2001; 345:1368-77.

Russell JA, et al. Vasopressin versus norepinephrine in patients with septic shock. N Engl J Med 2008; 358(9): 877-87.

Sprung CL, et al. Hydrocortisone therapy for patients with septic shock (CORTICUS). N Engl J Med 2008; 358: 111-24.

Within intensive care a core body temperature ≥38.3°C is considered a significant fever.

Causes

Within ICU the commonest cause of pyrexia is infection:

Intravascular devices and implants.

Pneumonia, VAP.

Intra-abdominal collections.

Colitis (especially C. difficile).

UTI, urinary catheter related sepsis.

Sinusitis (especially if using nasogastric or naso-endotracheal tubes).

Surgical site infections.

Non-infectious causes:

Postoperative fever.

Drug fever (e.g. β-lactam related), or drug withdrawal (e.g. alcohol).

Malignancy: lymphoma, leukaemia, solid cell tumours (especially renal), tumour lysis syndrome.

Infarction: myocardial, intracerebral, bowel, PE, fat emboli, stroke.

Venous thrombosis.

Inflammation: SIRS, ARDS, cytokine storm, hepatitis, pancreatitis, burns, gout, Dressler syndrome, immune reconstitution syndrome, Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction, transplant rejection.

Endocrine/metabolic: adrenal insufficiency, thyroid storm, malignant hyperpyrexia, NMS.

Blood product transfusion.

Presentation and assessment

Pyrexia may be associated with other evidence of infection, including:

Tachypnoea, tachycardia, rigors, sweats.

Complications of sepsis (see p.322).

p.322).

Raised WCC and/or inflammatory markers.

Other signs and symptoms may help identify the cause of the infection:1

Altered mentation: meningitis (TB, cryptococcal, carcinomatous, sarcoid), brucellosis, typhoid fever.

Arthritis/arthralgia: SLE, infective endocarditis, Lyme disease, lymphogranuloma venereum, Whipple’s disease, brucellosis, inflammatory bowel disease.

Animal contact: brucellosis, toxoplasmosis, cat scratch disease, psittacosis, leptospirosis, Q fever, rat bite fever.

Cough: tuberculosis, Q fever, typhoid fever, sarcoidosis, Legionella.

Epistaxis: Wegener’s granulomatosis, relapsing fever, psittacosis.

Epididymo-orchitis: TB, lymphoma, polyarteritis nodosa, brucellosis, leptospirosis, infectious mononucleosis.

Hepatomegaly: lymphoma, disseminated TB, metastatic carcinoma of liver, alcoholic liver disease, hepatoma, relapsing fever, granulomatous hepatitis, Q fever, typhoid fever, malaria, visceral leishmaniasis.

Lymphadenopathy: lymphoma, cat scratch disease, TB, lymphomogranuloma venereum, infectious mononucleosis, CMV infection, toxoplasmosis, HIV, brucellosis, Whipple’s disease, Kikuchi’s disease.

Renal angle tenderness: perinephric abscess, chronic pyelonephritis.

Splenomegaly: leukaemia, lymphoma, TB, brucellosis, subacute bacterial endocarditis, cytomegalovirus infection, EBV mononucleosis, rheumatoid arthritis, sarcoidosis, psittacosis, relapsing fever, alcoholic liver disease, typhoid fever, Kikuchi’s disease.

Splenic abscess: subacute bacterial endocarditis, brucellosis, enteric fever, melioidosis.

Conjunctival suffusion: leptospirosis, relapsing fever, Rocky Mountain spotted fever.

Subconjunctival haemorrhage: infective endocarditis, trichinosis, leptospirosis.

Uveitis: TB, sarcoidosis, adult Still’s disease, systemic lupus erythematosus, Behçet’s disease.

Investigations

FBC and differential (check for eosinophils).

Blood culture from all lines, and a peripheral ‘stab’.

Samples for culture with/without microscopy, Gram stain, fungal culture, AFBs:

Samples from all drains and any effusions that can be tapped

Swabs from nose, throat, naso-pharynx and perineum (for culture and/or viral PCR)

Urine (also do a dipstick test)

If diarrhoea is present stool culture and C. difficile toxin testing

Blood smear if malaria a possibility

ECG.

CXR.

Other imaging: US of abdomen, CT of any suspect area (especially after major surgery), sinus X-rays, white cell scans.

Differential diagnoses

Exclude measurement errors (check core temperature if possible).

Immediate management

Give O2 as required, support airway, breathing, and circulation

Review the patient’s history including, including drug history, sexual history, travel, occupation and exposure to animals.

Look for any obvious site of infection including:

Cannulae, epidural and catheter entry sites for redness/pus

Skin especially the back of the patient and buttocks

Check for enlarged lymph nodes

Review all previous investigations, looking for changes in inflammatory markers, WCC, ↑ insulin requirements, alteration in oxygen requirements, ↑ lactate, reduced absorption of feed

Further management

Remove as many non-essential invasive devices as possible, especially if blood drawn from a line produces a positive blood culture.

If blood cultures remain negative but the patient is still clinically unwell, continue broad-spectrum antibiotics for 48 hours and review.

Consider introducing antifungal medications if the patient condition is deteriorating and the fever remains high.

Treat with antipyrexial agents with/without surface cooling if there is limited cardiovascular reserve, brain injury, or pyrexia is >39.5°C.

Pitfalls/difficult situations

Pyrexia precedes other signs for ≥3 days in some infections, including viral hepatitis, EBV, measles, leptospirosis, typhoid.

TTE is often technically difficult on mechanically ventilated patients.

Hypothermia may also be associated with infection.

If temperature persists despite 5-7 days of adequate antibiotic cover stop antibiotics for 12 hours, re-culture, and start different antibiotics.

CVVH often causes low temperatures and can mask signs of fever.

Patients may become colonized, but not infected with, organisms.

Consider the possibility of rare/tropical infections; or biological agents.

Immunocompromised patients may be at risk from unusual infections which are difficult to identify/culture (see HIV, p.376, and neutropaenia,

p.376, and neutropaenia,  p.308); in neutropaenia micro-organisms may include:2

p.308); in neutropaenia micro-organisms may include:2

Lung: Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Pneumococci, Alpha-haemolytic streptococci, Acinetobacter species, Klebsiella, Aspergilllus

Abdomen: E. coli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Clostridium spp., Enterococcus spp., Klebsiella spp.

Urogenital: E. coli, Klebsiella spp., Pseudomonas aeruginosa,

Soft tissue: S. aureus, Alpha-haemolytic streptococci

Intravascular catheters: coagulase negative staphylococci, Corynebacteriae, Propionibacterium species, Candida spp.

Unknown: coagulase negative staphylococci, E. coli, Enterococcus spp.

References

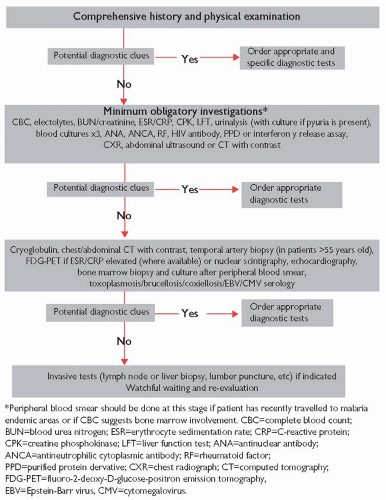

1. Varghese GM, et al. Investigating and managing pyrexia of unknown origin in adults. Br Med J 2010; 341: 878-81.

2. Penack O, et al. Management of sepsis in neutropenic patients: guidelines of the infectious diseases: guidelines from the infectious diseases working party of the German Society of Hematology and Oncology. Ann Oncol 2011; 22(5): 1019-29.

Further reading

Laupland KB. Fever in the critically ill medical patient. Crit Care Med 2009; 3(S): S273-S278.

Marik PE. Fever in ICU. Chest 2000; 117: 855-69.

O’Grady NP, et al. Guidelines for evaluation of new fever in critically ill adult patients: 2008 update from the American College of Critical Care Medicine and the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Crit Care Med 2008; 36: 1330-49.

(See also  p.32.)

p.32.)

p.32.)

p.32.)Airway infections can cause localized inflammation and oedema with or without systemic sepsis. Infection may also spread into the deep tissues of the neck or mediastinum. Mediastinitis may also result from contiguous spread after oesophageal rupture or sternotomy.

Causes

Airway infections

Pharyngeal, retropharyngeal, or peri-tonsillar abscess.

Ludwig’s angina or deep-neck infections (often polymicrobial).

Epiglottitis or diphtheria.

Mediastinitis

Mediastinal extension of dental or neck infection.

Tracheal perforation.

Oesophageal perforation (traumatic, post-surgical anastomotic breakdown, spontaneous/Boerhaave syndrome); associated with malignancy or infection (e.g. TB).

Post-sternotomy surgical site infection (e.g. after cardiac surgery).

Presentation and assessment

Signs/symptoms of infection ( p.322) may be accompanied by:

p.322) may be accompanied by:

p.322) may be accompanied by:

p.322) may be accompanied by:

Increasing respiratory distress, tachypnoea, dyspnoea, hypoxia.

Airway infections may cause:

Stridor.

‘Hunched’ posture; sitting forward, mouth open, tongue protruding.

‘Muffled’ or hoarse voice, sore throat, painful swallowing, drooling.

Neck swelling, or trismus.

Mediastinitis may be associated with:

A history of coughing, choking, or vomiting (Boerhaave syndrome).

Recent oesophageal surgery or endoscopy.

Signs associated with pneumothorax, or hydrothorax (i.e. percussion note and auscultation changes); most commonly left sided.

Investigations

(See  p.324.)

p.324.)

p.324.)

p.324.)Other investigations will depend on the presentation, but may include:

Throat swabs.1

Lateral soft tissue neck X-ray may demonstrate swelling and loss of airway cross-section (‘thumb print’ and ‘vallecula’ signs).

Laryngoscopy (indirect or fibreoptic).1

CXR (pneumomediastinum, pneumothorax or hydrothorax).

Oesophagoscopy.

Water soluble contrast swallow (or barium swallow).

Differential diagnoses

Airway foreign body or tumour; traumatic pneumo- or haemothorax

Further management

Airway or dental abscesses should be assessed by ENT specialists in case surgical drainage or dental extraction is required.

Thoracic surgical advice should be sought where mediastinal collections or oesophageal perforation are suspected; early presentation of an oesophageal perforation may be amenable to repair.

Oesophageal perforation will require feeding to be post-pyloric (nasojejunal, or jejunostomy) or parenteral.

In cases of airway infection assess for airway swelling (laryngoscopy/cuff-leak test) prior to extubation.

Pitfalls/difficult situations

In cases of airway infection, delaying intubation may make a difficult intubation impossible.

Spontaneous oesophageal rupture may present very late with gross contamination of the pleura and a large hydropneumothorax; small-bore chest drains are often insufficient.

1Airway interventions in a patient with a partially obstructed airway can provoke complete airway obstruction.

Further reading

Ames WA, et al. Adult epiglottitis: an under-recognized, life-threatening condition Br J Anaesth 2000; 85: 795-7.

Ridder GJ, et al. Descending necrotizing mediastinitis: contemporary trends in etiology, diagnosis, management, and outcome. Ann Surg 2010; 251(3): 528-34.

Kaman L, et al. Management of esophageal perforation in adults. Gastroenterol Res 2010; 3(6): 235-44.

Khan AZ, et al. Boerhaave’s syndrome: diagnosis and surgical management. Surgeon 2007; 5(1): 39-44.

(See also  p.62.)

p.62.)

p.62.)

p.62.)Pneumonia can occur as a result of infection acquired in the community or in hospital/health-care settings. In hospitalized patients, oropharyngeal overgrowth of enteric organisms, Pseudomonas, or Candida amongst the flora increases the risk of pneumonia after aspiration/micro-aspiration; pneumonia caused by drug-resistant organisms is also more common.

Abscesses may occur within the lung, or infection may spread from the lung to a parapneumonic effusion, resulting in an empyema. The mortality from lung abscess or empyema is 10-20%.

Causes

Pneumonia-causing organisms vary according to where it is acquired:

Infection may be caused by:

‘Typical’ organisms (S. pneumoniae, H. influenzae).

‘Atypical’ organisms (i.e. insensitive to penicillins: Legionella, Mycoplasma, Chlamydophila species, Coxiella burnetti).

Viruses (e.g. influenza A and B).

Uncommon organisms, often associated with chronic illness and hospitalization (S. aureus, M. catarrhalis, K. pneumonia, Pseudomonas, E. coli, Enterobacter, Acinetobacter).

Where there is no response to treatment or the patient is immunocompromised consider less common causes:

Resistant species: MRSA, resistant Pseudomonas.

Viral: varicella, CMV.

Fungal: Candida spp., Aspergillus.

Empyema:

Community-acquired empyema is most commonly associated with streptococcal infections (50%), as well as Staphylococci, anaerobes and Gram-negative organisms.

Hospital-acquired empyema is often caused by S. aureus (including MRSA), as well as Pseudomonas, E. coli, and Enterobacter.

Lung abscess:

Organisms include aerobic organisms (S. aureus, H. influenzae, Klebsiella species, S. milleri, S. pyogenes) and anaerobes (Prevotella, Bacteroides, Fusobacterium spp.); often polymicrobial.

Associated with S. aureus, K. pneumonia, and Pseudomonas.

Associated with bronchial carcinoma, aspiration, prolonged pneumonia, liver disease, dental disease, and IV drug use (septic embolization).

See Table 10.1 for incidence of pneumonia-causing organisms.

Presentation and assessment

Signs and symptoms of infection ( p.322) may be accompanied by:

p.322) may be accompanied by:

p.322) may be accompanied by:

p.322) may be accompanied by:

Increasing respiratory distress, tachypnoea, dyspnoea.

Cough, purulent sputum, haemoptysis, or pleuritic chest pain.

Features of coexisting disease (e.g. COPD or bronchiectasis).

CXR changes of collapse, consolidation or parapneumonic effusion.

Atypical pathogens should be suspected where the following are present:

Dry cough and/or multisystem involvement (e.g. headache, abnormal LFTs, elevated serum creatine kinase, hyponatraemia).

A history of travel, pets, high-risk occupations, comorbid disease.

Immunosuppressive disease or therapy.

Symptoms occur ≥48 hours after hospital admission.

The patient is readmitted ≤10 days after discharge from hospital.

Residence in a nursing home or extended care facility where there is recent or prolonged antibiotic use (e.g. leg ulcer treatment).

Receiving care for a chronic condition.

Patients with a neurological injury or ↓ consciousness level.

Difficulty swallowing (e.g. stroke, Parkinson’s disease), or NG feeding.

In patients mechanically ventilated for >48 hours by means of an ETT or tracheostomy, where there is:

Empyema: pleural effusion is a common ICU finding, suspect infection if:

Sepsis or inflammatory markers do not resolve.

Imaging suggests fibrin stranding or loculation.

Pleural tap reveals fluid that is turbid or has decreased pH.

Multiple drug resistance (MDR) may be present if:

The patient has been on prolonged antibiotic therapy, or there is a failure to respond to appropriate antibiotics.

Immunosuppressive disease or therapy is present.

The patient is receiving care for a chronic condition (e.g. dialysis).

The patient, their relatives, or the place where they are treated, are known to be associated with multidrug-resistant pathogens.

Investigations

(See  pp.63 and 324.)

pp.63 and 324.)

pp.63 and 324.)

pp.63 and 324.)Also consider:

ABGs (hypoxia, acidosis, or respiratory alkalosis).

U&Es (↓Na; ↑urea/creatinine).

CXR (infiltrates, consolidation, effusion, or cavitation).

Urine for Pneumococcal antigen and Legionella antigen.

Viral throat swab PCR.

Bronchoscopy or non-directed BAL (if safe to do so) testing for:

Culture and sensitivity (including AFBs, fungus, Legionella)

Immunofluorescence (e.g. influenza, Pneumocystis, Mycoplasma)

Other: viral PCR; galactomannan (Aspergillus)

Pleural fluid (if present) for microscopy, culture (±AFBs) and pneumococcal antigen:

Also assess for pH (pH testing is unnecessary if pleural fluid is cloudy or turbid), protein, LDH, cytology, glucose, and amylase

Differential diagnoses

Pneumonia: acute MI/pulmonary oedema; PE, pneumothorax, pneumonitis, vasculitis, sarcoidosis, or malignancy.

Empyema:

Immediate management

Follow guidelines on  pp.62 and 325.

pp.62 and 325.

pp.62 and 325.

pp.62 and 325.

Support airway, breathing, and circulation.

Suggested empirical antimicrobials

If associated with influenza add flucloxacillin IV 2 g 6-hourly

Aspiration pneumonia: co-amoxiclav IV 1.2 g 8-hourly:

For severe, in-hospital aspiration add gentamicin IV 5 mg/kg daily

Atypical pathogens suspected: co-amoxiclav IV 1.2 g 8-hourly and clarithromycin IV 500 mg or levofloxacin IV 500 mg 12-hourly

HAP/HCAP/VAP: piptazobactam 4.5 g IV 8-hourly ± linezolid 600 mg IV 12-hourly (avoid using previously used antibiotics)

In immunocompromised patients, or where any of the following are suspected treat accordingly:

Pneumocystis jiroveci: co-trimoxazole IV 120 mg/kg/day for 3 days, followed by 90 mg/kg/day for a further 18 days (and steroids)

Fungal infections: liposomal amphotericin B IV (dose depends upon formulation)

Viral infections: influenza, oseltamivir PO/NG 75 mg 12-hourly; herpes, aciclovir IV 10 mg/kg 8-hourly; CMV, ganciclovir IV 5 mg/kg 12-hourly

TB: seek advice from respiratory or infectious diseases specialists

MDR organisms suspected add:

Resistant Acinetobacter: amikacin IV 7.5mg/kg 12-hourly

Further management

(See also  pp.65 and 326.)

pp.65 and 326.)

pp.65 and 326.)

pp.65 and 326.)

Report notifiable diseases such as Legionella (see p.380).

p.380).

Pleural fluid drainage is indicated if:

The fluid is cloudy or turbid

The pH is <7.2 and infection is suspected

Infection is identified on Gram stain or culture

The effusion is loculated

Clinical condition deteriorates and infection is suspected

Complications such as empyema or abscess may require surgical treatment.

Pitfalls/difficult situations

Malignancies or foreign bodies may give rise to pneumonia, empyema, or lung abscesses.

Pneumonia, and especially lung abscesses, may be polymicrobial.

Consider Legionella where there is evidence of other organ failure (especially renal) and/or a community outbreak.

If necrotizing pneumonia caused by a PVL-producing strain of S. aureus is suspected see p.356.

p.356.

Table 10.1 Incidence of pneumonia-causing organisms | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Further reading

American Thoracic Society. Guidelines for the management of adults with hospital-acquired, ventilator-associated, and healthcare-associated pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2005; 171: 388-416.

Lim WS, et al. British Thoracic Society Guidelines for the management of community acquired pneumonia in adults: update 2009. Thorax 2009; 64(sIII): iii1-iii55.

Maskell NA, et al. BTS guidelines for the investigation of a unilateral pleural effusion in adults. Thorax 2003; 58(S2): ii8-ii17.

Masterton RG, et al. Guidelines for the management of hospital-acquired pneumonia in the UK: Report of the Working Party on Hospital-Acquired Pneumonia of the British Society for Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. J Antimicrob Chemother 2008; 62: 5-34.

Walters J, et al. Pus in the thorax: management of empyema and lung abscess. CEACCP 2011; 11(6): 229-33.

Infective endocarditis (IE) is sometimes also referred to as bacterial endocarditis, or subacute bacterial endocarditis (SBE). It can be caused by bacteria or fungi, which initially cause heart valve vegetation, followed by later valve destruction and abscess formation.

Causes

Underlying aortic or mitral valve disease; or rheumatic disease.

Prosthetic heart valves, or other intracardiac devices (e.g. pacemakers or defibrillators).

IV drug use or chronic vascular access (e.g. haemodialysis).

Infective organisms include:

Viridans Streptococci (e.g. S. mutans, S. mitis, S. sanguis, S. salivarius, Gemella morbillum); associated with oral/dental infections.

S. milleri, S. anginosus (associated with abscess formation).

S. aureus (including MRSA); coagulase negative staphylococci.

Enterococci (e.g. E. faecalis, E. faecium, E. durans).

Gram-negative ‘HACEK’ group bacilli (e.g. Haemophilus species, Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans, Cardiobacterium hominis, Eikenella corrodens, Kingella spp.).

Coxiella burnetii, Bartonella, Chlamydophila/Chlamydia (associated with negative blood cultures).

Fungi (e.g. Candida spp.).

Presentation and assessment

Fever is the most common sign; other signs/symptoms of infection ( p.322) may be accompanied by:

p.322) may be accompanied by:

p.322) may be accompanied by:

p.322) may be accompanied by:

Heart murmurs (especially regurgitant).

New heart failure or conduction abnormalities.

Left-sided (mitral or aortic) phenomenon:

Osler’s nodes; Janeway lesions; splinter haemorrhages; purpuric lesions; Roth spots

Metastatic abscesses or infarcts (lung, heart, brain)

Splenomegaly

Glomerulonephritis; microscopic haematuria

Right-sided (tricuspid or pulmonary) phenomenon:

Pulmonary embolism or abscess.

Infection may be more likely if:

Suspicious organisms are cultured.

Dental infections are present.

There is evidence of IV drug abuse (i.e. ‘track’ marks).

Intracardiac devices or prosthetic valves are present.

Known cardiac valve defects or a previous history of endocarditis.

Investigations

(See  p.324.)

p.324.)

p.324.)

p.324.)Also consider:

Serial blood cultures (from multiple sites, repeated every 24-48 hours).

Serial CRP measurements.

Serology (especially for Coxiella burnetti, Bartonella, Chlamydia, Candida, Aspergillus).

Urine dipstick (microscopic haematuria).

ECG (conduction abnormalities).

Transthoracic/transoesophageal echocardiography (vegetations, abscesses, valve aneurysms/pseudoaneurysms, valve perforation, prosthetic valve dehiscence).

Tissue sample culture (following surgery).

Differential diagnoses

Systemic infections causing multiple abscesses.

Immediate management

Follow guidelines on  p.325.

p.325.

p.325.

p.325.

Give O2 as required, support airway, breathing, and circulation.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

p.574

p.574 p.383

p.383 p.53

p.53

p.33

p.33