Trauma, Burns, and Skin Injury

Trauma is the biggest killer in the UK of those under the age of 45. Trauma deaths can be divided into 3 phases: those that occur at the time of injury, those that occur in the first few hours (and are largely preventable) and those occurring weeks later.

Critical care involvement may include:

At the accident scene as part of a medical emergency response team (MERIT).

In the ED as part of a trauma team.

Receiving the trauma patient from theatre.

Caring for the patient on the ICU.

Admitting patients with complications from the ward.

Causes

Causes of trauma can be categorized into blunt and penetrating (most trauma in the UK is blunt). Knowledge of the mechanism of injury can help predict injury patterns.

Blunt mechanisms

Road traffic collisions:

Pedestrian versus car; car versus car; motor bike accident (MBA)

Ejection from car; turned-over car

Fatality of others at the scene of the accident

Intrusion into the ‘cockpit’ of >30 cm

Falls from height (>3 m, or 5 stairs); fall from a horse.

Sporting injuries.

Assaults.

Penetrating mechanisms

Stabbings.

Gunshot wounds (GSWs).

Impalement.

Any patient with a significant mechanism should be transported to a major trauma centre where a trauma team is on standby to receive them.

Life-threatening injuries may have already been identified and managed in the 1° survey in the ED and operating theatre prior to the patient’s admission to critical care. However, new pathologies can develop, or old ones recur. Always return to the ATLS style of management should a trauma patient become unstable.

Limb-threatening injuries (i.e. compartment syndrome) may not have been identified prior to ICU admission, or may have developed during resuscitative measures.

Life-threatening injuries

Airway obstruction (e.g. laryngeal or tracheal injury):

Head injury with impaired consciousness

Breathing injuries:

Pneumothorax (tension, open), or massive haemothorax

High spinal injury

Flail chest

Cardiac injuries (tamponade or cardiac contusion).

Severe haemorrhage:

Major arterial damage

Intra-abdominal bleeding

Pelvic fracture or bilateral femoral fractures

Acute coagulopathy of trauma

Intracranial lesions.

Hypothermia.

Limb-threatening injuries

Traumatic amputation.

Vascular injury/compromise.

Open fracture.

Compartment syndrome.

Crush injury.

Approach

Assessment of trauma patients should follow a set routine, elucidating and treating life- and limb-threatening injuries as they are found, in the order in which they will harm the patient (an ‘ATLS approach’). In all cases it is essential to ensure that those treating the patient are safe to carry out their work.

A 1° survey (following the ABC format) should be performed and life-threatening injuries treated simultaneously. For example, if there is catastrophic haemorrhage (e.g. major blast/ballistic injury, or traumatic amputation) the 1° survey is be modified to deal with this first.

Trauma primary survey: ABC approach

Primary survey

Airway (and C-spine or other spinal immobilization)

Breathing (and ventilatory control)

Circulation (and haemorrhage control)

Disability (and neurological care)

Exposure (and temperature control)

Obtain a history and detailed information; the minimum should include an ‘AMPLE’ history ( p.2).

p.2).

p.2).

p.2).Obtain information from the patient, relatives, or paramedics concerning the mechanism of injury

Immediate investigations and decision-making

Bloods, including crossmatch and β-HCG as needed

Pelvic X-ray

Decision-making: is there a need for urgent transfer (e.g. for a CT scan, urgent surgery, transfer to a major trauma centre)?

Immediate management

Perform 1° survey, initial resuscitation, and investigations.

Obtain an AMPLE history ( p.2).

p.2).

Primary survey

Airway

Examine for: airway obstruction: ↓ conscious level, foreign body/matter, expanding neck haematoma, laryngeal fracture, stridor.

If obstruction is present perform a jaw thrust and insert an oro/nasopharyngeal airway if required (chin lift and head-tilt should be avoided in patients with suspected C-spine injuries):

Avoid nasopharyngeal airways if BOS fracture is suspected

Where obstruction is present, or likely to occur, consider endotracheal intubation or an emergency needle cricothyroidotomy/tracheostomy (see pp.522 and 528).

pp.522 and 528).

Breathing

Look for evidence of respiratory compromise: hypoxia (reduced PaO2 or SaO2), dyspnoea, and/or tachypnoea, absent or abnormal chest movement, loss of chest wall integrity (flail segment), pulmonary aspiration, massive bleeding.

Exclude/treat life-threatening conditions (e.g. tension pneumothorax, massive haemothorax1).

Consider endotracheal intubation and mechanical ventilation in patients with actual or imminent respiratory distress.

Circulation

Look for evidence of circulatory inadequacy: tachycardia, weak pulse, hypotension, cold peripheries, prolonged capillary refill (>2 seconds, but difficult to interpret in associated hypothermia).

Look for obvious or concealed blood/fluid loss: palpate the abdomen, feel for blood pools (flanks, hollow of neck/back, groin), look for pelvic instability, look for long-bone fractures.

Exclude life-threatening conditions such as cardiac tamponade (raised CVP/JVP, pulsus paradoxus, diminished heart sounds, low voltage ECG), tension pneumothorax,2 haemorrhage or arrhythmia:

Assess degree of shock ( p.104)

p.104)

Establish wide-bore IV access (2 × 16G cannulae), if not possible consider intraosseous or central access ( pp.536 and 542)

pp.536 and 542)

Commence fluid/blood replacement and treatment of hypovolaemic shock; give 500 ml of colloid within 5-10 minutes and reassess:

Follow a major haemorrhage protocol ( p.115)

p.115)

Permissive hypotension ( p.106) may be appropriate in some cases whilst awaiting definitive haemorrhage control

p.106) may be appropriate in some cases whilst awaiting definitive haemorrhage control

Various initial resuscitation targets in trauma exist, one example is:

Head injury: systolic of 90 mmHg

Blunt trauma: systolic of 90 mmHg

Penetrating injury: systolic of 60-70 mmHg

Pre-existing hypertension: patient’s usual MAP

Haemorrhage control may require:

Direct pressure, or indirect pressure (e.g. femoral artery)

Elevation (where possible)

Wound packing

Windlass dressing, or tourniquets where required

Novel haemostatic agents (e.g. Celox®, Quickclot®)

Disability/neurology

Exposure/general

Measure the patient’s core temperature:

Rewarming should be commenced if required3

Establish full exposure of affected area.

Provide analgesia as required.

Investigations

ABGs may aid resuscitation.

Finger-prick blood sugar test should be measured.

As soon as IV access is established take the following blood tests:

Crossmatch.

Coagulation test (especially during haemorrhage resuscitation; bedside coagulation screen may be available).

Serum glucose.

Consider paracetamol, salicylate, alcohol levels.

βHCG (in women of childbearing age).

Also consider:

Bench co-oximetry for carbon monoxide.

ECG.

Where severe abdominal bleeding is suspected consider performing diagnostic peritoneal lavage (DPL) to confirm the presence of blood (where scanning is not available).

Imaging of major trauma should include:

Other long bones may be X-rayed as clinically indicated.

AP and ‘peg’ views of the C-spine may also be considered, but CT of neck may be more appropriate (see pp.182 and 408).

pp.182 and 408).

CT of head, chest, neck, or abdomen/pelvis may be required.

Other imaging that may be required:

Long-bone X-rays.

CT angiography.

Retrograde urethrogram.

Chest X-ray findings associated with traumatic aortic disruption

Widened mediastinum

Distorted, poorly defined aortic knuckle

Tracheal deviation (to the right)

Loss of space between the pulmonary artery and the aorta

Depression of the left main bronchus

Oesophageal/nasogastric tube deviation (to the right)

Paratracheal striping

Left haemothorax

Fractures of ribs 1 or 2; scapula fractures

Pleural or apical caps

Widened paraspinal interfaces

Specific injuries involving critical care

Spinal cord injuries

In major trauma all patients should initially be assumed to have a spinal injury and spinal precautions used including hard collar, sand bags, head strapping, and log-rolling:

The patient must be moved from the long board, once stable, onto a mattress to prevent early pressure sores developing

High spinal injuries (C1-C3) may present with dyspnoea, accessory muscle use, and ventilatory failure, necessitating early endotracheal intubation and ventilation:

Suxamethonium is safe to use within the first 48 hours of a spinal injury; once muscle atrophy occurs there is a risk of hyperkalaemia

Spinal shock and autonomic disruption may occur; other causes of hypotension such as occult haemorrhage should be excluded:

Spinal shock may require vasopressors

Bradycardia may occur

There is controversy about the use of high-dose steroids within the first 8 hours of spinal cord injuries: if used give methylprednisolone IV 30 mg/kg in 15 minutes, then 5.4 mg/kg/hour for 23 hours.

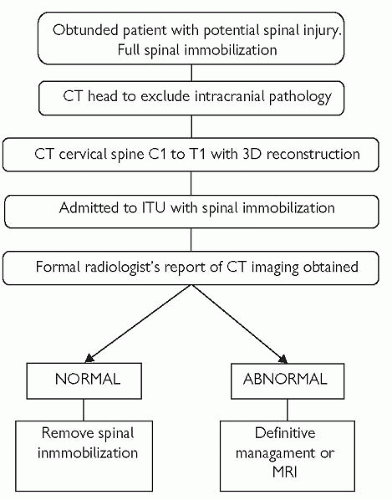

Where it has not been possible to rule out spinal cord injury in an unconscious patient admitted to the ICU, carry out the investigations recommended on pp.182 and 408.

pp.182 and 408.

Thermoregulation: patients are unable to regulate body temperature and require warming in the early phase of the injury.

Urinary retention: all patients require catheterization.

Autonomic dysreflexia: sudden peripheral stimuli may precipitate hypertensive crises.

Considerations for the long-term care of paralysed patients may be found on p.197.

p.197.

Pneumothorax/tension pneumothorax

(See  p.80.)

p.80.)

p.80.)

p.80.)

Open chest wounds have the potential to cause lung collapse and impaired gas exchange; sealing them completely risks development of a tension pneumothorax:

They should be sealed on 3 sides, with 1 side left free to allow air to escape; alternatively use Asherman or Bowlin chest seals.

Haemothorax

(See  p.82.)

p.82.)

p.82.)

p.82.)

This may occur early, at the time of the injury, or late if intercostal vessels are damaged by fractured ribs.

Rib fractures, flail chest, pulmonary contusion

Severe pain may limit the ability of the patient to cough or deep breathe; a thoracic epidural may be required for pain relief:

Atelectasis and pneumonia may occur as a late complication of rib fractures, especially where respiration is limited by pain

The presence of rib fractures increases the likelihood of pneumothoraces, especially in mechanically ventilated patients.

The presence of multiple rib fractures, especially the upper 3-4 ribs, is associated with underlying lung, mediastinal, and C-spine injury.

Flail chest occurs when a segment of chest wall loses continuity with the rest of the bony structure (usually as a result of 2 fractures) and effectively ‘floats free’:

In normal respiration the chest can expand and generate a negative pressure, where a flail segment is present it may be sucked in by the negative pressure, rather than air through the airways

Paradoxical breathing may be obvious (flail segment moving in with respiration).

Dyspnoea, tachypnoea may be present.

Endotracheal intubation and mechanical ventilation are likely to be required.

Pulmonary contusions may develop in the first 24 hours after blunt chest injury causing characteristic CXR changes:

Cardiac contusion

Cardiac contusion may occur as a result of blunt chest injuries.

Hypotension and ECG changes may occur: arrhythmias, VEs, sinus tachycardia, AF, RBBB, ST segment changes.

ECG monitoring should be continued for 24 hours as severe arrhythmias may develop.

Severe right-sided contusions may result in a raised CVP.

Myocardial ischaemia may have precipitated the trauma.

A troponin rise is common and does not usually represent ischaemic damage to the myocardium.

Contusion usually settles without significant cardiac comorbidity.

Aortic disruption

Rapid deceleration injuries affecting the chest may cause disruption of the great vessels, which may initially be contained by haematoma.

Hypotension is normally caused by another bleeding site (as rapid aortic bleeding is mostly fatal).

If suspected, obtain vascular or cardiothoracic surgical advice.

Avoid surges in BP; infusions of hypotensive agents such as labetalol or esmolol may be required.

Shooting

‘Low’-velocity (handgun bullets) injuries cause damage along the bullet track; ‘high’-velocity (rifle bullets) injuries may cause extensive cavitation areas within the wound.

Entrance/exit wound size does not predict the degree of wound cavity.

Bullet or bone fragments may cause further damage.

The wound tract will be soiled by environmental contaminants:

Wound exploration, debridement and excision may be undertaken; delayed 1° suture (DPS) is likely to be necessary

Antibiotic prophylaxis should be given.

p.28

p.28 p.146

p.146 p.408

p.408