55 Indications for and Management of Tracheostomy

Tracheostomy is one of the most commonly performed surgical procedures in critically ill patients who require prolonged mechanical ventilation.1 A large body of literature describes the potential benefits, risks, and technical aspects of this procedure, but there is little guidance as to what constitutes optimal tracheostomy practice in the critically ill patient.2,3 This chapter reviews basic aspects of tracheostomy management, focusing in particular on indications, timing, technique, and postprocedure care.

Indications for Tracheostomy

Indications for Tracheostomy

The presence of a “difficult airway” in a patient requiring prolonged mechanical ventilatory support constitutes an absolute indication for tracheostomy. Patients with so-called difficult airways include those with conditions such as significant maxillofacial trauma, angioedema, obstructing upper-airway tumors, or other anatomic characteristics that would render translaryngeal intubation technically difficult to perform in the event of inadvertent airway loss. Patients with difficult airways represent a small fraction of all individuals undergoing tracheostomy. More commonly, patients undergo this procedure for subjective indications (e.g., to facilitate ventilator weaning, to promote oral hygiene and pulmonary toilet, or to enhance comfort).4 Tracheostomy is most commonly performed in an elective fashion; accordingly, patients should be clinically optimized to minimize risk (e.g., minimal ventilatory support [FIO2 ≤ 50%, PEEP ≤ 7.5 cm H2O], hemodynamically stable, metabolic and hemostatic derangements corrected). Because many of the benefits of tracheostomy relative to prolonged translaryngeal intubation are unproven, unambiguous criteria for selecting patients for tracheostomy are lacking.3

Timing of Tracheostomy in Acute Respiratory Failure

Timing of Tracheostomy in Acute Respiratory Failure

In the early years of critical care medicine, endotracheal tubes (ETTs) were composed of rigid materials and incorporated a low-volume, high-pressure pneumatic cuff. During this era, it became common practice to perform tracheostomy early—within 48 hours of initiating mechanical ventilation—in an effort to minimize laryngeal and tracheal injury associated with endotracheal intubation.5 With advances in ETT design, the trauma associated with prolonged translaryngeal intubation lessened.5 Further, a prospective study examining risks associated with tracheostomy suggested that this procedure was accompanied by high rates of morbidity and mortality.6 Accordingly, enthusiasm for the routine performance of tracheostomy waned. With refinement in techniques, perioperative complication rates associated with tracheostomy diminished. In addition, subsequent studies attempting to establish the relationship between prolonged translaryngeal intubation, prolonged tracheostomy, and laryngeotracheal damage produced conflicting findings.5 At present, no data clearly establish that translaryngeal intubation should be limited to any specific duration or that tracheostomy should be performed at any specific point in a patient’s course in an effort either to limit chronic laryngeal dysfunction or minimize tracheal injury.

Recent investigations examining timing of tracheostomy have focused on duration of mechanical ventilation and related measures of resource expenditure. Rodriguez et al. assigned 106 patients who developed acute respiratory failure following major trauma to either undergo tracheostomy within 7 days of intensive care unit (ICU) admission (“early” tracheostomy) or to tracheostomy at least 8 days following ICU admission (“late” tracheostomy). Compared to patients undergoing late tracheostomy, patients in the early tracheostomy group had a trend toward a lower incidence of pneumonia, as well as significant reductions in duration of mechanical ventilation, ICU length of stay, and hospital length of stay.7 Likewise, Lesnik et al. reported a retrospective analysis of 101 patients who developed acute respiratory failure following blunt trauma, comparing patients who underwent early tracheostomy (within 4 days of ICU admission) to late tracheostomy (>4 days following ICU admission). Compared to patients undergoing late tracheostomy, patients in whom tracheostomy was established early had a significantly shorter duration of mechanical ventilation and lower incidence of pneumonia.8 Others have likewise reported a benefit of early tracheostomy.9,10 In contrast, Blot et al. reported that neutropenic patients developing acute respiratory failure who underwent early tracheostomy (within 48 hours of intubation) had longer duration of mechanical ventilation and longer hospital length of stay than did patients who either underwent tracheostomy formation after 7 days or not at all.11 Given the conflicting results, variability in study quality, heterogeneity in populations enrolled, and inconsistency in endpoints studied, it is difficult to draw on the conclusions of these and similar studies to ascertain the optimal timing of tracheostomy creation. As a consequence, tracheostomy practice varies substantially.1

There are several reasons why tracheostomy may facilitate weaning from mechanical ventilation.5 Resistance to airflow in an artificial airway is proportional to air turbulence, tube diameter, and tube length. Air turbulence is increased in the presence of extrinsic compression and inspissated secretions.12 Airflow resistance and associated work of breathing should theoretically be less with tracheostomies than with ETTs because of an ETT’s rigid design, shorter length, and removable inner cannula (to allow for evacuation of secretions).12 Further, the presence of a tracheostomy may allow clinicians to be more aggressive in weaning patients from mechanical ventilation. Specifically, if a patient with a tracheostomy tube in place does not tolerate liberation from ventilatory support, he or she may be simply reconnected to the ventilator. In contrast, if a patient who is translaryngeally intubated does not tolerate extubation, he or she must be sedated and reintubated. This might represent a potential barrier to extubation in patients who are of marginal pulmonary status. Finally, patients with tracheostomies may receive less sedation than individuals with translaryngeal airways.13 Reduction in sedation may be accompanied by increases in mobility, differences in approaches to and success of weaning, and other factors that may shorten duration of ventilatory support.

Technical Considerations

Traditionally, tracheostomies have been performed in the operating room using standard surgical principles.14 In 1985, Ciaglia et al. described percutaneous dilational tracheostomy (PDT) in which tracheostomy is accomplished via a modified Seldinger technique, typically with the aid of bronchoscopy.15 PDT has subsequently gained wide acceptance and has become the predominate method of tracheostomy creation in many centers.16–18

There are several potential advantages of PDT relative to surgically created tracheostomies (SCT). PDT may be performed at the bedside, avoiding the inconvenience and risk of transporting a critically ill patient, as well as the expense of utilizing operating room resources. In a prospective randomized study comparing PDT and SCT, Freeman et al. found that PDT was associated with a reduction of approximately $1500 in patient charges per procedure.19 Other investigators have reported comparable findings.20 In addition, a meta-analysis of prospective trials comparing PDT with SCT suggests that PDT may be associated with fewer complications, specifically postprocedure bleeding and peristomal infection.21 The reduction in these complications may reflect that there is minimal dead space between the tracheostomy tube and adjacent pretracheal tissues following PDT, which may have a tamponading effect on minor bleeding and serve as a barrier to infection.21 Finally, PDT is relatively simple to learn. Individuals who have not received formal surgical training may become facile with this procedure and perform it safely and effectively.17,22

While there are many potential advantages of PDT, this procedure has been associated with a number of highly morbid complications, many of which (e.g., pretracheal insertion, tracheal laceration, esophageal perforation, pneumothorax, loss of airway) are unusual in surgically created tracheostomies.23–28 Accordingly, whereas PDT may be performed competently by those not trained in surgical techniques, persons who are expert at surgical airway management should be immediately available in the event complications arise.22

Selection, Maintenance, and Care of Tracheostomy Tubes

Selection, Maintenance, and Care of Tracheostomy Tubes

Tracheostomy Tube Selection

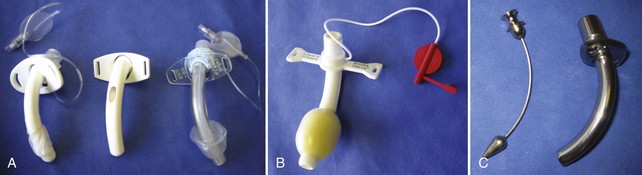

A detailed discussion of the various types and designs of tracheostomy tubes is beyond the scope of this text, but a working knowledge of tracheostomy tube features is essential to the competent care of patients who have undergone placement of these devices (Figure 55-1). Briefly, most tracheostomy tubes are manufactured from polyvinyl chloride, silicone, a combination of these materials, or metal. They are available in either single-lumen (no removable inner cannula) or dual-lumen (removable inner cannula) configurations. The purpose of the removable inner cannula is to facilitate cleaning of inspissated secretions that may lead to tube occlusion. Because silicone is relatively secretion resistant, tubes manufactured from this material frequently do not have an inner cannula. Tracheostomy tubes are available with and without pneumatic cuffs. The purpose of the cuff is to maintain a seal between the tube and the tracheal mucosa sufficient to prevent escape of air from around the tracheostomy tube during mechanical ventilation (i.e., cuff leak). Further, the cuff minimizes but does not prevent aspiration. Tracheostomy tubes with foam cuffs conform to a patient’s trachea and remain consistently inflated at low pressure. These tubes are indicated in patients who have sustained damage from excessive cuff pressure (e.g., tracheomalacia). Once a cuffed tracheostomy tube is no longer required—that is, the patient no longer requires mechanical ventilatory support and is not considered an aspiration risk—the cuffed tube is exchanged for a cuffless tube. Tracheostomy caps are generally provided with tracheostomy tubes for use in the decannulation process (see later discussion). Fenestrated tubes are used to promote speech and are generally used in individuals who tolerate liberation from mechanical ventilation for varying periods of time. Fenestrated tubes have an opening on their superior aspect such that when the inner cannula is removed, the cuff deflated, and the external orifice occluded (such as with a Passey-Muir type valve), air can pass the vocal cords, allowing phonation.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree