INTRODUCTION

PRIMARY HIV INFECTION

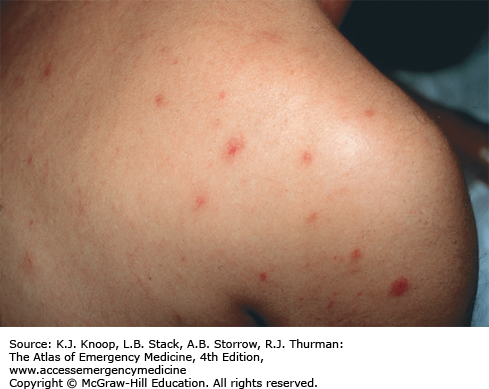

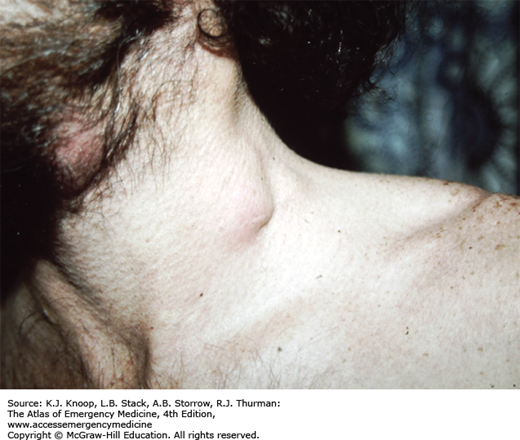

Establishing a definitive diagnosis in the earliest stage of HIV infection can have significant impact on the patient’s outcome and may serve a public health function as well. Patients are highly infectious during acute seroconversion and may be unaware that they are infected. It is believed that a significant number of the new cases of HIV infection occurring in the United States are acquired from acutely infected individuals. Identifying acute seroconverters could offer the opportunity to discuss transmission reduction behavior. Clinical illness accompanies primary HIV infection in approximately two-thirds of patients. The usual time from HIV exposure to the development of symptoms is approximately 10 to 20 days, with average symptom duration of 1.5 to 2 weeks. The most common symptoms following seroconversion mimic a typical viral syndrome and may include mucocutaneous lesions and a generalized maculopapular rash located over the face, neck, and trunk. The rash is seen in over 50% of persons with symptomatic primary HIV infection. The lesions are typically small, well circumscribed, erythematous, nonpruritic, and nontender. Less frequently, patients may demonstrate neurologic signs and symptoms consistent with meningoencephalitis, myelopathy, and peripheral neuropathy. If obtained, laboratory studies may show lymphopenia and thrombocytopenia.

Although rapid HIV testing has become feasible in most emergency department (ED) settings, the diagnosis of acute infection cannot rely solely on rapid antibody-based tests. If the possibility of acute seroconversion is entertained, then a discussion should take place with the patient regarding level of risk behavior. If acute HIV is suspected, HIV-1 ribonucleic acid (RNA) quantitative polymerase chain reaction (PCR) is the appropriate diagnostic test. Patients who are acutely seroconverting should have extremely high levels of HIV RNA. Importantly, a negative HIV antibody test does not rule out HIV infection in these cases. During the “window period” of acute HIV infection, antibodies against the HIV virus have not yet formed and may not be detected for 8 to 10 weeks. If acute HIV is suspected or confirmed, patients should be educated about disease transmission and referred for prompt follow-up and further outpatient testing and evaluation.

Maintain a high degree of clinical suspicion for acute primary HIV infection, especially when sexually active patients or patients who use intravenous drugs present with mononucleosis-like symptoms, unexplained rash, mucocutaneous ulcers, lymphadenopathy, or aseptic meningitis.

Obtain an HIV RNA quantitative PCR (and not just an HIV antibody test) if acute HIV is suspected.

Ensure proper follow-up for patients in whom the diagnosis of acute HIV infection is entertained, and counsel patients regarding potential risk of transmission.

IMMUNE RECONSTITUTION INFLAMMATORY SYNDROME (IRIS)

Effective antiretroviral therapy establishes virologic suppression and can allow the patient’s immune system to rebuild to a near-normal competency. In some patients who develop a rapid immune response after a very advanced degree of immune suppression, the immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS) can develop. In these patients, it is thought that previously subclinical infections manifest with the development of a more robust immune status. IRIS is most often seen in patients who have recently started antiretroviral therapy (usually within 60 days of starting therapy) with an initial CD4 count below 100 cells/mm3. Most common infections that can “trigger” IRIS include mycobacterium (tuberculosis [TB] and mycobacterium avium complex [MAC]), cytomegalovirus (CMV), cryptococcal disease, and histoplasmosis. Patients typically present with fever, malaise, lymphadenopathy, and symptoms associated with the active opportunistic infection.

The key for the ED physician is to identify those patients who have recently started antiretroviral therapy and may be presenting with IRIS-related findings. Appropriate evaluation and management depends on the underlying opportunistic infection. Patients will often require admission to the hospital and consultation with an infectious diseases specialist.

HIV-infected patients who are currently taking antiretroviral therapy and present with a febrile illness should be questioned regarding the duration of antiretroviral therapy and pretreatment CD4 count. Patients with advanced disease who have recently started antiretroviral therapy may be presenting with signs and symptoms of IRIS-related disease.

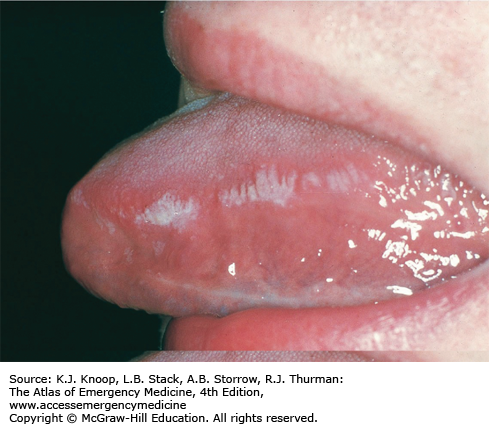

ORAL HAIRY LEUKOPLAKIA

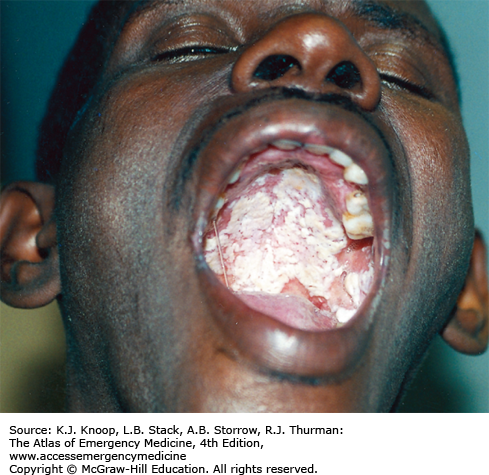

Oral hairy leukoplakia (OHL) is a disease of the lingual squamous epithelium caused by the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV). OHL generally affects the lateral portion of the tongue, although the floor of the mouth, palate, or buccal mucosa may also be involved. The lesions are white corrugated plaques that, unlike Candida, cannot be scraped from the surface to which they adhere. Most often OHL is asymptomatic, although occasionally this condition can be painful. Diagnosis is usually clinical, though definitive diagnosis can be made by biopsy characteristically revealing acanthosis and parakeratosis.

Patients who are known to be HIV-seropositive can be educated about the disease and reassured. OHL is not considered to be a premalignant lesion. If the patient is not known to be infected with HIV, primary care provider referral and HIV screening, if available, should be offered.

Oral candidiasis can be distinguished from OHL by utilizing a swab in an attempt to remove the exudate characteristic of thrush and by observing pseudohyphal elements microscopically with candida. OHL cannot be scraped off and usually involves the lateral aspect of the tongue.

OHL is fairly specific for HIV infection as it is rarely observed in patients with other immunodeficiencies. If OHL is identified in a patient not known to be HIV infected, risk factors and HIV screening options should be discussed.

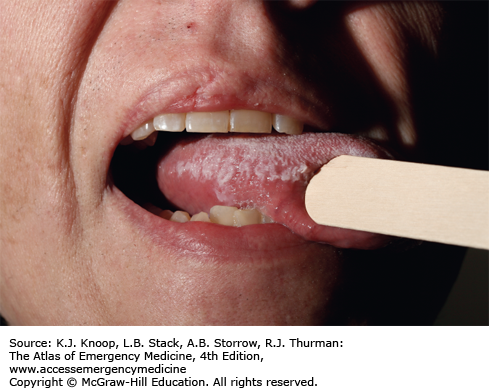

CANDIDIASIS ASSOCIATED WITH HIV

Oral candida infections are seen in over half of all HIV patients, with the severity of infection often correlating with the degree of immunosuppression. Oral candidiasis can occur at all stages of HIV disease. The usual causative agent is Candida albicans, but other Candida species have been isolated. Oral candidiasis, or “thrush,” can be classified as pseudomembranous, angular, or erythematous. Pseudomembranous candidiasis can be diagnosed by identifying removable whitish plaques on the tongue, uvula, and buccal mucosa. Erythematous or atrophic candidiasis appears as smooth red patches along the soft and hard palate. Although isolated oral candidiasis is not an AIDS-defining illness (though esophageal candidiasis is), oral candidiasis is an indication for pneumocystis prophylaxis regardless of CD4+ cell count.

Vaginal candidiasis is common in HIV positive patients and can cause a severe whitish discharge with vulvar erythema.

Patients presenting to the ED for dysphagia or odynophagia thought to be due to candidiasis should be evaluated for dehydration and may require inpatient admission. Most cases of minimally symptomatic oral candidiasis respond well to nystatin suspension or clotrimazole troches. More symptomatic oral or esophageal candidiasis usually responds to fluconazole. Rare cases of resistant candidiasis may require intravenous echinocandin therapy.

Symptomatic oral and esophageal candidiasis is still a common ED presentation in HIV patients who are not receiving or are not compliant with effective antiretroviral therapy.

The diagnosis of oral candidiasis in a patient not already diagnosed with HIV infection should lead to a discussion of risk factors and should prompt HIV screening.

Mildly symptomatic oral, esophageal, or vaginal candidiasis usually responds to a one-time oral dose of fluconazole. Close clinical follow-up should be arranged.

KAPOSI SARCOMA

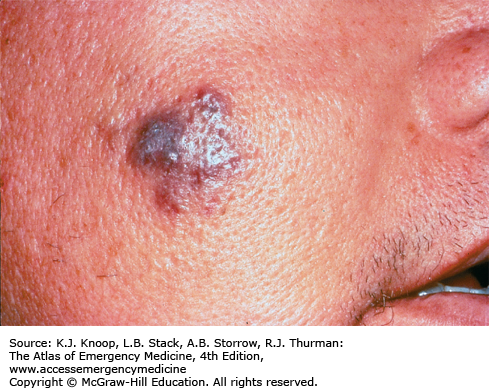

Kaposi sarcoma (KS) is a low-grade vascular tumor associated with human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8). Since the introduction of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), the incidence of KS in HIV-infected persons has significantly declined. Skin involvement is characteristic but extracutaneous spread of KS is common, particularly to the oral cavity, gastrointestinal (GI) tract, and respiratory tract. The skin lesions appear most often on the lower extremities, face (especially the nose), oral mucosa, and genitalia. Most commonly, the lesions are papular, ranging in size from several millimeters to centimeters in diameter. Less commonly, the lesions may be plaque-like, especially on the soles of the feet, or exophytic and fungating with breakdown of overlying skin. Papular lesions may resemble lesions associated with bacillary angiomatosis or herpesvirus infections.

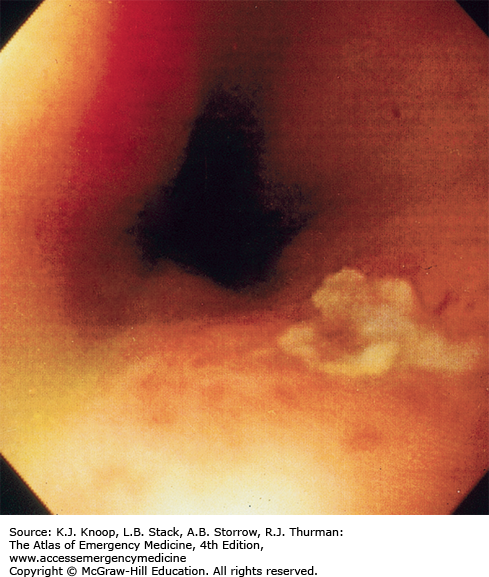

Pulmonary involvement can occur in AIDS-related KS. Affected persons may present with shortness of breath, fever, cough, hemoptysis, or chest pain or as an asymptomatic finding on chest x-ray. Diagnosis can be confirmed via bronchoscopy.

All HIV-infected patients with KS should receive antiretroviral therapy, which is generally effective in treating most cutaneous lesions. Systemic chemotherapy and newer immunomodulator therapy (interleukin-12, angiogenesis inhibitors) are reserved for more extensive disease including patients with visceral involvement.

HIV patients who present with new papular lesions should be referred for dermatologic evaluation and biopsy.

A careful examination of the skin and oral cavity is appropriate in HIV-infected patients presenting with GI or respiratory complaints.

Half of patients with oral involvement have other GI tract lesions as well. Hemoccult testing of stool is a good preliminary screen.

TOXOPLASMA GONDII INFECTION

Toxoplasma gondii is a widespread intracellular protozoan parasite with a definitive host stage in cats. Immunocompetent persons are usually asymptomatic, but immunocompromised persons (especially HIV-positive persons with <100 CD4 cells/μL) are susceptible to reactivation of latent disease with considerable morbidity and mortality.

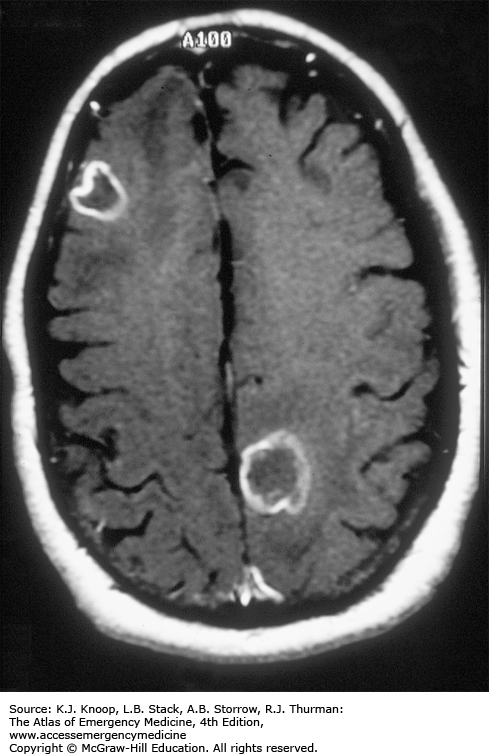

Patients with central nervous system (CNS) toxoplasmosis most often present with symptoms consistent with intracranial mass lesions (headache, focal neurologic deficit, nausea/emesis, and/or seizure) or, less likely, encephalitis (fever, confusion, altered mental status). Contrasted computed tomography (CT) of the head typically reveals ring-enhancing lesions with a predilection for the basal ganglia. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the head is more sensitive than CT for identifying these lesions. Serological tests for T gondii antibodies (IgG) are usually positive. Other causes of mass lesions in the brain in HIV-infected individuals include CNS lymphoma, cryptococcoma, tuberculoma, and brain abscess.

Ocular toxoplasmosis is a less frequent complication of HIV disease. Patients typically present with eye pain and decreased visual acuity. Retinitis may be diagnosed by ophthalmoscopic evaluation revealing characteristic exudates and hemorrhage. Toxoplasmosis retinitis appears as raised yellow-white, cottony lesions in a nonvascular distribution, unlike the edematous perivascular exudates of CMV retinitis.

There are two combination regimens considered to be first choice for the treatment of toxoplasmosis. The most commonly used regimen is pyrimethamine and sulfadiazine for 6 weeks or until neurological findings have resolved; however, for those with sulfa allergies, pyrimethamine and clindamycin is an alternative. If the patient presents with seizures, loading doses of antiepileptics such as fosphenytoin or levatiracetam should be administered along with benzodiazepines. All patients with acute symptomatic CNS toxoplasmosis infection should be admitted for treatment.

In cases of suspected ocular toxoplasmosis, a complete eye examination including slit-lamp examination and measurements of intraocular pressure should be performed before consulting ophthalmology.

HIV-infected patients presenting with focal neurologic findings or seizures should be evaluated for meningitis and space-occupying lesions in the brain. AIDS-specific differential includes toxoplasmic encephalitis, CNS lymphoma, and cryptococcal disease.

All HIV-infected patients should have a CNS space–occupying lesion excluded by imaging prior to lumbar puncture (LP).

Initial evaluation of the HIV-infected patient with possible CNS lesions should include CT or MRI imaging, LP, and triage management for bacterial meningitis. Further workup will require admission and infectious diseases consultation.

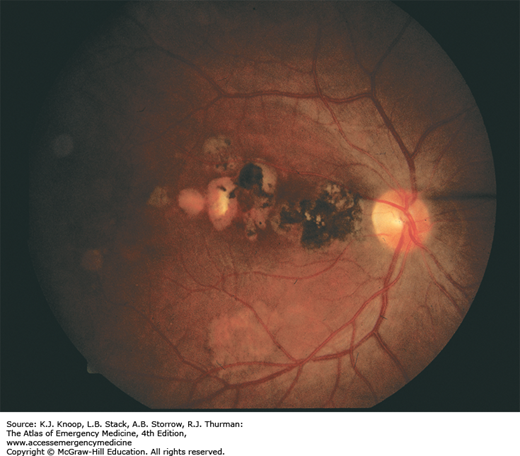

FIGURE 20.14

Toxoplasmosis Retinitis. Ocular toxoplasmosis is a common complication of HIV disease. The lesion is a focal destructive chorioretinitis which leaves well-defined, heavily pigmented scars, especially in the macular area. (Photo contributor: Department of Ophthalmology, Naval Medical Center, San Diego, CA.)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree