Hemoptysis is defined somewhat arbitrarily as mild (less than 20 mL of blood loss in 24 hours), moderate, or massive (greater than 600 mL of blood loss in 24 hours).

![]() Most cases are not life threatening—but all require careful evaluation.

Most cases are not life threatening—but all require careful evaluation.

![]() The most common causes include infection (eg, tuberculosis or TB), neoplasm, and cardiovascular disease. No cause is found in 28% of cases.

The most common causes include infection (eg, tuberculosis or TB), neoplasm, and cardiovascular disease. No cause is found in 28% of cases.

![]() Hemoptysis is found in all age groups, with a 60:40 male predominance.

Hemoptysis is found in all age groups, with a 60:40 male predominance.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

![]() The lung has dual blood supply from the pulmonary and bronchial arteries. Bleeding may result (1) from increased intravascular pressure, (2) from erosion into a blood vessel, or (3) as a complication of a coagu-lopathy.

The lung has dual blood supply from the pulmonary and bronchial arteries. Bleeding may result (1) from increased intravascular pressure, (2) from erosion into a blood vessel, or (3) as a complication of a coagu-lopathy.

![]() Hemoptysis due to increased intravascular pressure generally arises from a primary cardiac abnormality such as congestive heart failure (75% of cardiac cases) or, less commonly, mitral stenosis.

Hemoptysis due to increased intravascular pressure generally arises from a primary cardiac abnormality such as congestive heart failure (75% of cardiac cases) or, less commonly, mitral stenosis.

![]() Erosion into bronchial vessels, which are under systemic pressure, can lead to severe hemoptysis. This often is due to TB, bronchiectasis, or malignancy.

Erosion into bronchial vessels, which are under systemic pressure, can lead to severe hemoptysis. This often is due to TB, bronchiectasis, or malignancy.

CLINICAL FEATURES

![]() The acute onset of fever, cough, and bloody sputum suggests pneumonia or bronchitis. A more indolent productive cough may represent bronchitis or bronchiectasis.

The acute onset of fever, cough, and bloody sputum suggests pneumonia or bronchitis. A more indolent productive cough may represent bronchitis or bronchiectasis.

![]() Dyspnea and pleuritic chest pain are hallmarks of pulmonary embolism.

Dyspnea and pleuritic chest pain are hallmarks of pulmonary embolism.

![]() Fever, night sweats, and weight loss often reflect TB or malignancy. Chronic dyspnea and minor hemoptysis may represent mitral stenosis or alveolar hemorrhage syndromes (often associated with renal disease).

Fever, night sweats, and weight loss often reflect TB or malignancy. Chronic dyspnea and minor hemoptysis may represent mitral stenosis or alveolar hemorrhage syndromes (often associated with renal disease).

![]() Smoking, male gender, and age greater than 40 years are the main risk factors for neoplasm.

Smoking, male gender, and age greater than 40 years are the main risk factors for neoplasm.

![]() The physical examination is aimed at assessing the severity of hemoptysis and the underlying disease process, but is unreliable in localizing the site of bleeding.

The physical examination is aimed at assessing the severity of hemoptysis and the underlying disease process, but is unreliable in localizing the site of bleeding.

![]() Commonly associated findings include fever and tachypnea. Hypotension is rare except in massive hemoptysis. Cardiac examination may reveal signs of mitral stenosis. Lung auscultation, often normal, may reveal rales, wheezes, or signs of focal consolidation. Adenopathy or muscle wasting should increase concern for malignancy.

Commonly associated findings include fever and tachypnea. Hypotension is rare except in massive hemoptysis. Cardiac examination may reveal signs of mitral stenosis. Lung auscultation, often normal, may reveal rales, wheezes, or signs of focal consolidation. Adenopathy or muscle wasting should increase concern for malignancy.

![]() Careful inspection of the oral and nasal cavities is warranted to help exclude an extrapulmonary source of bleeding.

Careful inspection of the oral and nasal cavities is warranted to help exclude an extrapulmonary source of bleeding.

DIAGNOSIS AND DIFFERENTIAL

![]() The differential diagnosis of hemoptysis includes infection (bronchitis, pneumonia, TB, fungal pneumonia, and lung abscess), malignant lesions (primary lung neoplasms or metastatic tumors), cardiogenic causes (left ventricular failure or mitral stenosis), inflammatory causes (bronchiectasis or cystic fibrosis), trauma, foreign body aspiration, pulmonary embolism, primary pulmonary hypertension, vasculitis, and bleeding diathesis.

The differential diagnosis of hemoptysis includes infection (bronchitis, pneumonia, TB, fungal pneumonia, and lung abscess), malignant lesions (primary lung neoplasms or metastatic tumors), cardiogenic causes (left ventricular failure or mitral stenosis), inflammatory causes (bronchiectasis or cystic fibrosis), trauma, foreign body aspiration, pulmonary embolism, primary pulmonary hypertension, vasculitis, and bleeding diathesis.

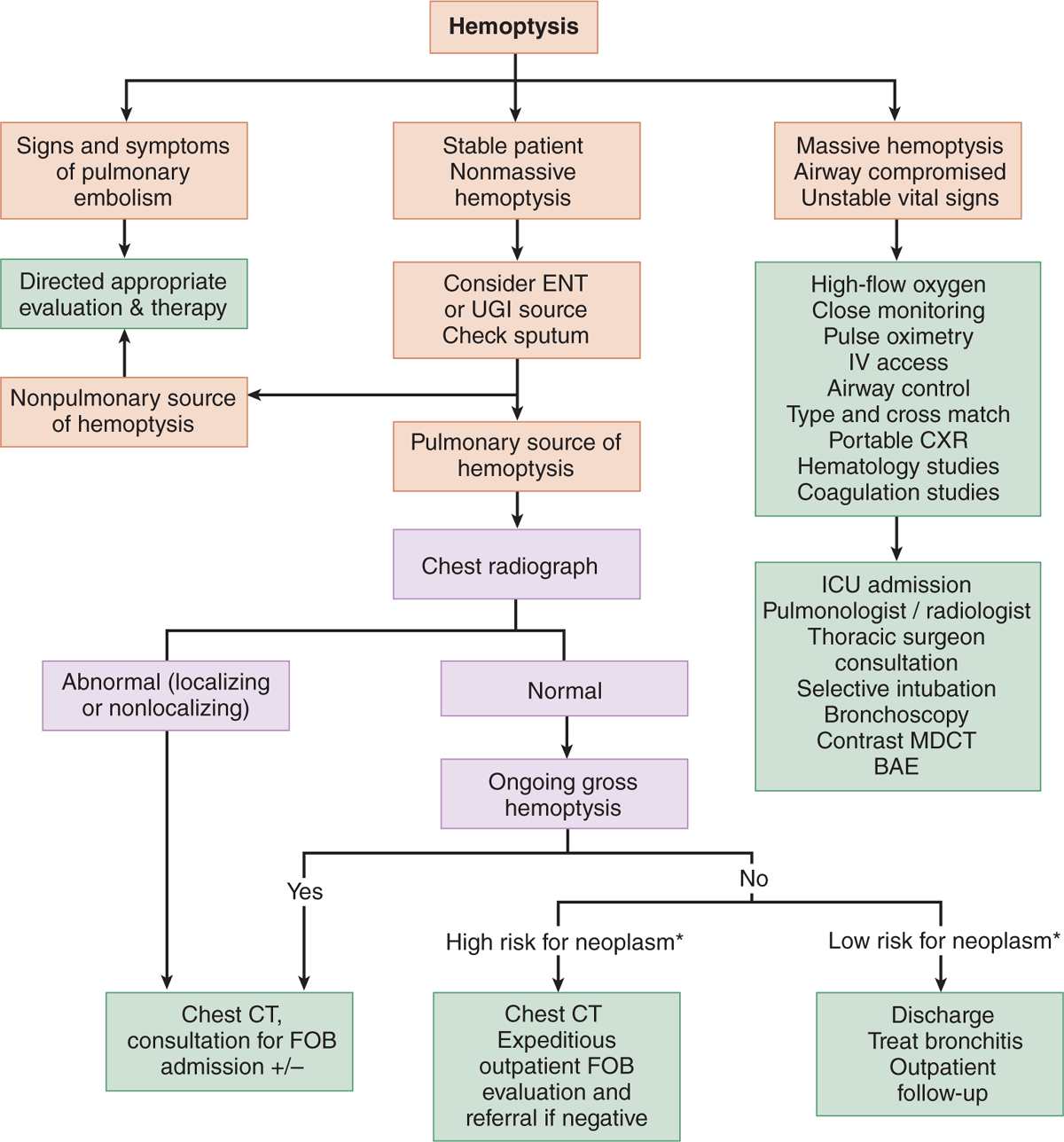

![]() Testing should include pulse oximetry and chest radiography (see Fig. 35-1). While 15% to 30% of all patients presenting with hemoptysis will have a normal chest radiograph, an abnormal chest radiograph is seen in the vast majority (80%-90%) of those with underlying malignancy; chest computed tomography (CT) should be considered in hemoptysis patients with abnormal chest radiographs.

Testing should include pulse oximetry and chest radiography (see Fig. 35-1). While 15% to 30% of all patients presenting with hemoptysis will have a normal chest radiograph, an abnormal chest radiograph is seen in the vast majority (80%-90%) of those with underlying malignancy; chest computed tomography (CT) should be considered in hemoptysis patients with abnormal chest radiographs.

![]() A hematocrit and type and crossmatch should be obtained in major hemoptysis. Other testing should be ordered as indicated by the clinical situation.

A hematocrit and type and crossmatch should be obtained in major hemoptysis. Other testing should be ordered as indicated by the clinical situation.

FIG. 35-1. Evaluation of hemoptysis. *High risk for neoplasm: age >40 years old, >40 pack-year smoking history, recurrent bleed, or no history consistent with lower respiratory tract infection. BAE = bronchial artery embolization; CXR = chest radiograph; ENT = ear, nose, and throat; FOB = fiber-optic bronchoscopy; ICU = intensive care unit; MDCT = multidetector CT; UGI = upper GI.

EMERGENCY DEPARTMENT CARE AND DISPOSITION

![]() ED treatment is based on hemoptysis severity and associated signs and symptoms. Initial management focuses on airway, breathing, and circulation. Cardiac and non-invasive blood pressure monitoring, along with pulse oximetry, should be utilized. Large-bore IV lines should be placed in patients with more severe presentations.

ED treatment is based on hemoptysis severity and associated signs and symptoms. Initial management focuses on airway, breathing, and circulation. Cardiac and non-invasive blood pressure monitoring, along with pulse oximetry, should be utilized. Large-bore IV lines should be placed in patients with more severe presentations.

![]() Administer supplemental oxygen as needed.

Administer supplemental oxygen as needed.

![]() Administer normal saline or lactated Ringer’s solution initially for hypotension. Packed red blood cells should be transfused as needed.

Administer normal saline or lactated Ringer’s solution initially for hypotension. Packed red blood cells should be transfused as needed.

![]() Fresh frozen plasma (two units) should be given to those patients with coagulopathies; platelets should be administered to those with thrombocytopenia.

Fresh frozen plasma (two units) should be given to those patients with coagulopathies; platelets should be administered to those with thrombocytopenia.

![]() Patients with ongoing massive hemoptysis may benefit from being placed in the decubitus position with the bleeding side down.

Patients with ongoing massive hemoptysis may benefit from being placed in the decubitus position with the bleeding side down.

![]() Cough suppression with opioids (eg, hydrocodone 5–15 milligrams every 4–6 hours) may prevent dis-lodgement of clots.

Cough suppression with opioids (eg, hydrocodone 5–15 milligrams every 4–6 hours) may prevent dis-lodgement of clots.

![]() Endotracheal intubation should be performed with a large tube (8.0 mm in adults) for persistent hemoptysis and worsening respiratory status. This will facilitate suctioning and bronchoscopy.

Endotracheal intubation should be performed with a large tube (8.0 mm in adults) for persistent hemoptysis and worsening respiratory status. This will facilitate suctioning and bronchoscopy.

![]() Indications for ICU admission include moderate or massive hemoptysis, or minor hemoptysis with a high risk of subsequent massive bleeding. Some underlying conditions may warrant admission regardless of the degree of bleeding.

Indications for ICU admission include moderate or massive hemoptysis, or minor hemoptysis with a high risk of subsequent massive bleeding. Some underlying conditions may warrant admission regardless of the degree of bleeding.

![]() All admissions should include consultation with a pulmonologist or a thoracic surgeon for help with decisions regarding bronchoscopy, CT scanning, or angiography for bronchial artery embolization.

All admissions should include consultation with a pulmonologist or a thoracic surgeon for help with decisions regarding bronchoscopy, CT scanning, or angiography for bronchial artery embolization.

![]() Patients who are discharged should be treated with cough suppressants, inhaled β-agonist bronchodilators, and antibiotics if an infectious etiology is suspected. Close follow-up is important.

Patients who are discharged should be treated with cough suppressants, inhaled β-agonist bronchodilators, and antibiotics if an infectious etiology is suspected. Close follow-up is important.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree