Hemoptysis

Sanjay Bhatt

Coughing up blood is a significant cause of concern to both the provider and patient. While a common symptom in adults, it is an uncommon presentation in children. The differential diagnosis can be diverse and includes pulmonary pathology as well as pseudohempotysis caused by ear, nose, and throat (ENT) or gastrointestinal pathology. Although typically indicative of primary pulmonary pathology, hemoptysis may result from numerous systemic illnesses. It is important to note that the severity of bleeding does not correlate with the gravity of the underlying disease.

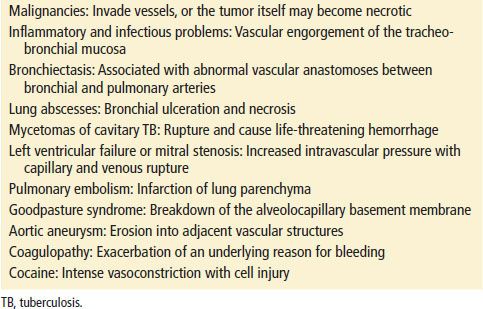

Hemoptysis is attributed to multiple underlying pathophysiologic mechanisms. Bleeding sources include bronchial and pulmonary arteries. In general, bronchial arteries are under high-pressure systems whereas pulmonary are under low-pressure systems. Massive bleeding, which accounts for 1.5% of cases, usually arises from injury to the high-pressure bronchial arteries (1–3). The cause of bleeding depends on the underlying etiology. Exsanguination is rarely the cause of death in hemoptysis; rather, blood can obstruct distal alveoli thereby impairing gas exchange. In these cases, death can result from hypoxemia. There are several possible causes for bleeding; Table 80.1 lists the multitude causes of bleeding in a patient presentation to the emergency department (ED).

TABLE 80.1

Mechanisms of Bleeding in Hemoptysis

CLINICAL PRESENTATION AND DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Patients may present to the ED with a chief complaint of “coughing up blood.” The extent of this bleeding can range from minor to copious. While the vast majority of patients have stable vital signs, those with pulmonary compromise may reflect some degree of tachycardia. Those with severe bleeding may show signs of hypoxemia, hemodynamic instability, and/or airway compromise. Patients with systemic diseases, such as Goodpasture syndrome, may present with hematuria and hemoptysis.

Pseudohemoptysis should be excluded before the pulmonary causes of hemoptysis are entertained. An appropriate history and physical examination can eliminate gastrointestinal and otolaryngologic sources. The vomitus of gastrointestinal bleeding tends to be darker in color and may contain food particles. In comparison, true hemoptysis is typically bright red and frothy. Mouth, throat, and nasopharyngeal sources of bleeding may be visualized with direct, indirect, or fiberoptic laryngoscopy.

The etiology of hemoptysis worldwide can vary by country (4). In the United States, the most common causes include infections, malignancy, bronchiectasis, bronchitis, and cardiovascular disorders (5–7). Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease is an independent risk factor for hemoptysis (1). Worldwide, while tuberculosis (TB) is still the most common cause of hemoptysis, it is much less common in the United States (8). In areas such as New York City or Los Angeles that house a large TB population, this diagnosis must be considered.

While uncommon, patient with systemic lupus erythematous (SLE) may present with alveolar hemorrhage and resultant hemoptysis (9). Travelers or immigrants, especially those from Asia, the Middle East, and South America, may have parasitic infections (3). Catamenial hemoptysis, which is hemoptysis during menstruation, may occur in women with thoracic endometriosis (1,10). In those who are immunocompromised, bacterial pneumonia is a common diagnosis while in the HIV population, Kaposi’s sarcoma must be considered (1).

Independent of coagulation parameters, patients on immunosuppressive medications, or those with a history of transbronchial biopsy or lung transplant, are at an increased risk for hemoptysis after bronchoscopy (11). It is important to note that the mortality rate among lung transplant patients who present with hemoptysis is high (12). Occult malignancy should always be considered, especially in those with a long-standing smoking history.

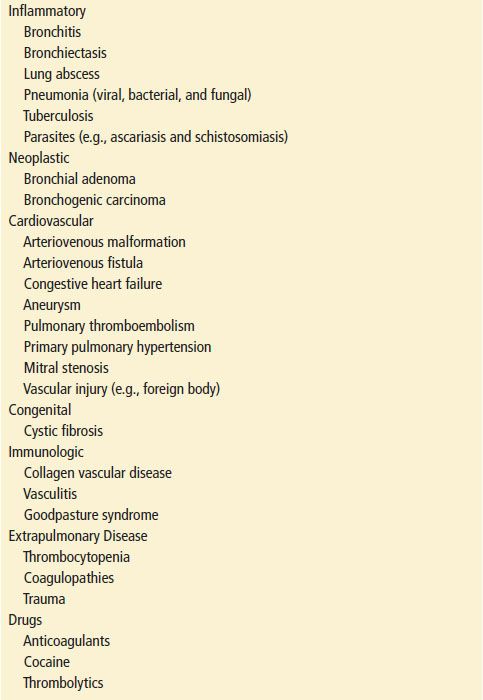

Three potential biologic weapons that may present with hemoptysis include plague, tularemia, and T2 mycotoxin (2). Table 80.2 lists the common causes of hemoptysis by category.

TABLE 80.2

Common Causes of Hemoptysis

In pediatric patients, lower respiratory tract infections account for almost 40% of all presentations of hemoptysis. Other causes include cystic fibrosis (CF), foreign-body aspiration, bronchial adenomas, and trauma. All providers must be aware of accidental as well as deliberate trauma; bleeding caused by deliberate suffocation has been described (1). CF may be associated with recurrent, severe bleeding in both children and young adults. Hemoptysis in children with CF occurs with increasing age and advancing disease and almost 60% of children will have at least one episode. Most of these episodes are not life-threatening (13). Although congenital heart disease and mitral stenosis after rheumatic fever are still reported causes of hemoptysis, corrective surgery for the former and decreasing incidence of the latter make them infrequent causes of bleeding (13). Other uncommon causes include bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia (7), pulmonary embolism, Wegener granuloma, primary pulmonary hemosiderosis, and arteriovenous malformations (AVMs) (5,13).

ED EVALUATION

Patients with massive hemoptysis require initial focus on the airway, breathing, and circulation (ABCs) of support; as noted above, especially given concern for asphyxiation and lesser so exsanguination. The ABCs take precedence to making a definitive diagnosis. While providers agree that massive hemoptysis describes the expectoration of a large amount of blood or a rapid rate of bleeding, the thresholds that define massive hemoptysis remain controversial. Thresholds range from 100 to 1000 mL (14) over 24 hours though none has been generally accepted. Some clinicians argue that abnormal gas exchange and hemodynamic instability, generally tachycardia or tachypnea, should be part of the definition.

Nevertheless, patients who present with what is termed “massive” hemoptysis have a mortality rate close to 50% (6). Similar to the adult definition, the pediatric definition of massive hemoptysis can vary; some sources define the rate of bleeding as 8 mL/kg/24 hrs (13). While massive versus submassive bleeding carries both diagnostic and prognostic implications, this differentiation is difficult to perform in the ED. Similar to adult presentation, mortality is primarily due to asphyxiation and lesser so exsanguination.

Most series list TB and bronchiectasis as the most common causes of massive hemoptysis; other diseases include lung abscesses, malignancy, Goodpasture syndrome, Behçet disease, AV malformations, trauma, coagulopathies, and aspergillomas (3).

As almost any amount of bleeding may prove detrimental to patients with limited cardiopulmonary reserve or significant underlying disease, baseline cardiopulmonary status, and overall physical condition must weigh into a physician’s decision to pursue aggressive measures. History, physical examination, and laboratory studies can help evaluate the patient’s ability to respond to the physiologic stress of hemoptysis and the therapy it necessitates.

Once a patient has been stabilized, efforts to determine the cause of hemoptysis should include a thorough history and physical examination. Laboratory studies should include: a complete blood count to determine the chronicity and magnitude of bleeding and the need for a platelet transfusion; a urinalysis and creatinine values in those whom pulmonary renal syndromes are being considered; arterial blood gas analysis and a pulse oximetry to determine oxygenation; coagulation studies to determine whether fresh-frozen plasma may be of benefit; and sputum evaluation in those whom TB is considered, radiograph studies should include a chest x-ray to evaluate for a multitude of diagnosis including neoplasm and focal infections. A chest computed tomography may better identify malignancies, infections, and pulmonary emboli. The combination of high-resolution CT scan and bronchoscopy is the standard by which a diagnosis is established (2,4,15). Definitive diagnosis may require sputum cytology, pulmonary function testing, angiography, or specialized sputum studies (2,15).

Aggressive management must occur at the same time as evaluation. Some diagnostic modalities, most notably bronchial artery embolization, are both diagnostic and therapeutic (4,16–18). Some centers are now using a new technique of bronchoscopic endobronchial sealing with cyanoacrylate (19).

Even after exhaustive study, 10% of cases will have no identifiable etiology (3). These patients are classified as having idiopathic or cryptogenic hemoptysis; in these cases, it is presumed that subtle airway or parenchymal disease is the culprit. Close follow-up to exclude repeat presentation and malignancy is especially important (20).

KEY TESTING

• Pulse oximetry

• CXR

• CBC

• Coagulation studies