Headache

Jonathan A. Edlow

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

Headache is the reason for approximately 2% of all emergency department (ED) visits (1). This large number of patients can be divided into two groups—those with benign causes (≥95%) and those with treatable illnesses that are life, limb, vision, or brain threatening (≤5%) (1,2). These two groups are not always easily distinguished, and delay in the diagnosis of meningitis and subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) is an important reason for malpractice payments in emergency medicine (3).

The brain parenchyma is insensate (4). Head pain results from tension, traction, distention, dilation, or inflammation of the pain-sensitive structures external to the skull, portions of the dura, and the blood vessels. Because all of these mechanisms are likely mediated by a final common biochemical pathway resulting in pain, a favorable response to analgesics, or even the more specific antimigraine agents, should not be used to judge the cause of an individual headache (5).

These basic facts highlight two points: Headache is common, and the potential for serious diagnostic error exists. Given that emergency physicians work under both time and resource utilization pressures, physicians must develop a logical, practical, and accurate approach to distinguish between the two groups of patients (6,7).

Physicians have three tools to make this critical distinction: The history, the physical examination, and diagnostic tests.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

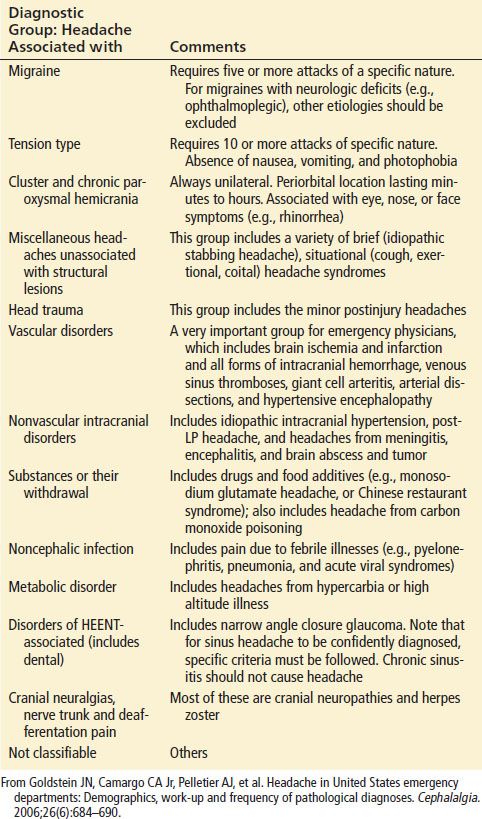

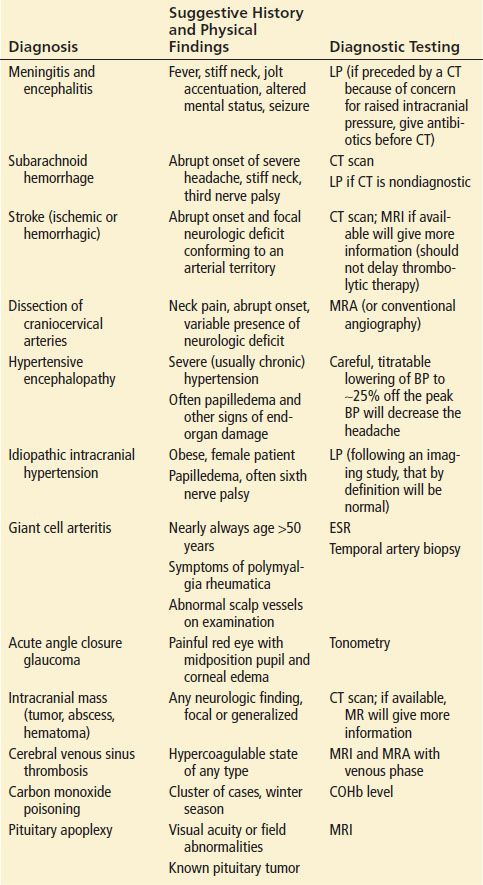

The differential diagnosis of headache can be organized in several ways. The International Headache Society method (Table 12.1), although comprehensive, is cumbersome for use in the ED. Another method of sorting the differential diagnosis is by temporal pattern. For example, is the current headache a chronic recurring one or is it a new-onset unusual event? Still a third method, and one that is consistent with the way emergency physicians work, is the division of headaches into the two groups listed previously. The problems that are life, limb, brain, or vision threatening are referred to as cannot-miss diagnoses (6,8). These disorders result in serious morbidity or mortality if untreated (Table 12.2).

TABLE 12.1

International Headache Society Classification

TABLE 12.2

“Cannot Miss” Causes of Headache (see Text for Definition)

Overall, primary headache disorders such as migraine, cluster, and tension headaches are by far the most common causes of headache (9). Detailed discussions of the primary headache syndromes and the other individual disease entities are discussed in other chapters (Chapters 156 and 157). This chapter focuses on strategies to avoid missing these cannot-miss diagnoses.

DIAGNOSTIC APPROACH

The physician has two parallel and related goals: Correct diagnosis and effective treatment, with the first goal facilitating the second. Not only is it perfectly acceptable to begin treating the pain before the diagnosis is made, but it is preferable. Faster pain control results in greater patient satisfaction and more rapid disposition, and if a subsequent lumbar puncture (LP) is needed, a more relaxed patient.

Because most patients have benign causes of their headaches, and because of the limiting issues of both time and cost, most patients do not require further evaluation beyond history and physical examination. Physicians must decide who requires further evaluation and who can be safely treated and discharged with appropriate follow-up.

All patients with acute headache associated with new neurologic deficits must be evaluated sufficiently to explain the cause of those deficits. The same is true for those with significant abnormalities in the head, eyes, ears, nose, and throat (HEENT) examinations and the vital signs. However, the more common and more difficult situation is the patient whose physical examination is normal. In this group of patients, physicians must use the history, past medical and family history, and other epidemiologic factors to decide upon further evaluation. As with any painful symptom, the standard attributes of the pain—location, severity, quality, onset, timing and duration, associated symptoms, alleviating and exacerbating factors—are used to try to make the distinction between benign and cannot-miss diagnoses. Each of these factors must be factored into the equation. There is no single response to any single question that automatically triggers a workup.

The location of pain is less helpful in making this distinction than it is with other types of pain; there is significant overlap between benign and serious causes (8). Some recommend working up patients whose headaches are consistently on the same side (10). Severity of pain also has limitations. Although the “worst-of-life” headache suggests a more serious problem, most severe headaches in the ED have benign causes (11,12). This is partly because of the variability of patients’ pain thresholds and partly because overall, most headaches have benign causes. That said, increasing severity should lower one’s threshold for further diagnostic testing, and most patients with the abrupt onset of a worst-of-life headache should be evaluated for SAH (8). Defining the quality of pain is crucial (8). It is important to ask in detail about the patient’s prior headaches. A new headache that is qualitatively unique and unusual for the patient may be more significant than the “worst-ever” headache in another patient whose current headache is similar in quality to prior episodes, only more severe. Onset is another important feature that drives decision-making. Abrupt or “thunderclap” onset suggests intracranial hemorrhage or cerebral venous sinus thrombosis, although once again, there is a broad differential diagnosis, and most abrupt-onset headaches are benign (13). For abrupt-onset headaches, the activity at onset sometimes suggests the etiology, for example, in coital headache or benign exertional headache (14,15). However, although these activities are sensitive for the corresponding diagnoses, they are not specific; SAH must be ruled out. Importantly, many SAH patients develop their headache during quiet activity or even sleep (16).

Defining the timing and duration of the pain is useful. Worrisome features include new acute headache, or a subacute headache that is increasing in severity. Long-standing duration (years) of a headache or a similarly long history of intermittent headaches is less likely to be a cannot-miss cause, assuming that sufficient history is taken to ensure that there is nothing new or different to the prior headache pattern. Very fleeting headaches, termed jabs and jolts, that last seconds are generally benign (17).

Similarly, associated symptoms can be important. Nausea and vomiting occur with migraine but also suggest intracranial mass, blood, or infection. Again, comparison with prior headaches is important. The significance in a patient with migraines who always vomits with them is different from the migraineur who is now vomiting for the first time. The same is true of photophobia. Visual abnormalities suggest migraine, idiopathic intracranial hypertension, temporal arteritis, and pituitary apoplexy. Diplopia from a pupil-involving third nerve palsy suggests a cerebral aneurysm or other mass (18). Diplopia from a sixth nerve palsy is seen with elevated or abnormally low intracranial pressure of any cause, presumably due to stretching of the sixth cranial nerve. Associated syncope, seizure, or any focal neurologic symptoms associated with a new headache should generally prompt an evaluation.

Exacerbating and alleviating factors are less helpful with headache. For example, the classic history that a headache from brain tumor increases on awakening is neither specific nor sensitive (19). It is also seen in patients with chronic lung disease and hypercarbia (which worsens during sleep). Headache from intracranial hypotension, either spontaneous or post-LP tends to worsen on standing upright, and headache due to acute sinusitis often worsens on bending forward with the head dependent (20). In terms of alleviating factors, diagnostic significance should not be ascribed to pain relief, even with over-the-counter medications. New medications or the discontinuation of a medication may also be diagnostically relevant in some patients (21).

Patients frequently use the word migraine loosely to refer to any bad headache or sinusitis to refer to any frontal headache. Unless these diagnoses have been substantiated by a prior medical evaluation, it is preferable to simply use the less specific but more accurate word headache (6). Sinusitis is a relatively uncommon cause of headaches; many of these patients actually have migraines (22,23). Tension headaches and migraines are very common. The lifetime incidence of migraine is about 11% (24); therefore, even patients with true histories of tension headaches or migraines will occasionally develop new headaches of another cause. This fact underscores the importance of carefully exploring the difference between a patient’s prior headache and the one that led to the current ED visit.

The epidemiologic context is important. A family or past history of cerebral aneurysm increases the likelihood of an aneurysmal cause. Poorly treated hypertension may lead to hypertensive encephalopathy. Vascular risk factors can result in stroke. Hypercoagulability or a past or family history of thromboembolic events should raise the possibility of cerebral venous sinus thrombosis. Obesity increases the possibility of idiopathic intracranial hypertension (pseudotumor cerebri), especially in women. New-onset headache at older ages also suggests a secondary cause (1,2). Most migraine headaches begin before age 30, and very few begin after age 50. Therefore, physicians must have a lower threshold to work up older patients with new headaches. Specifically, giant cell arteritis, tumors, subdural hematoma, and medication-related headaches should be considered in this group. Patients who are HIV positive or have a history of cancer represent other groups in whom a lower threshold to pursue evaluation seems justified. Winter season and common source clusters are associated with carbon monoxide poisoning. Although migraine is the most common cause of headache in pregnancy, other disorders such as stroke, SAH, cerebral venous sinus thrombosis, and of course eclampsia must also be considered (25).

The International Headache Society definition of tension and migraine headaches requires multiple episodes to definitively diagnose migraine or tension headache (26). Migraine is defined by 5 or more episodes of a throbbing headache that has certain characteristics (7), and tension headache is defined as 10 or more episodes. Although all of these patients must have their first headache at some point in time, most do not present to the ED. Therefore, diagnosing a patient with a new, different headache with a primary headache disorder opens the door to misdiagnosis.

The physical examination starts with the general appearance and vital signs. General appearance can be deceiving and is, at least in part, a function of a given patient’s pain threshold. Nevertheless, the patient who is shielding the eyes from the light, while consistent with migraine, also suggests meningeal irritation. Fever is not a symptom of migraine and suggests infection or a several-day-old SAH.

Isolated hypertension is an uncommon cause of headache; however, it is a common result of headache. Patients with headache may have a high blood pressure reading due to the pain, stress, or the presence of underlying intracranial pathology. Reducing the blood pressure and treating the pain pharmacologically may make the patient look and feel better without identifying the underlying etiology. In some specific causes of headache, such as stroke, overzealous blood pressure reduction can be detrimental (27). On the other hand, in hypertensive encephalopathy (elevated blood pressure with signs of end-organ damage), the headache is directly related to the elevated pressure. In these cases, reduction of the blood pressure by about 25% of its peak value is usually followed by rapid improvement of the patient’s symptoms. The emergency physician should have a low threshold for brain imaging (and possibly LP) in patients with hypertension and a headache that is otherwise worrisome based on onset, severity, quality, and associated symptoms.

The emergency physician should also look for signs of meningeal irritation. Meningismus, stiffness on passive flexion of the neck (to be distinguished from just pain without stiffness on neck flexion) results from infections (meningitis) or irritation (SAH). However, this finding is not reliably present, and its absence does not exclude either condition. The same is true of Kernig and Brudzinski signs (see Chapter 185). One physical finding that has been found to be more reliable in meningitis is jolt accentuation. This sign is positive if, when the patient is asked to turn their head horizontally (as if shaking their head “no”) two to three rotations per second, the baseline headache increases (28).

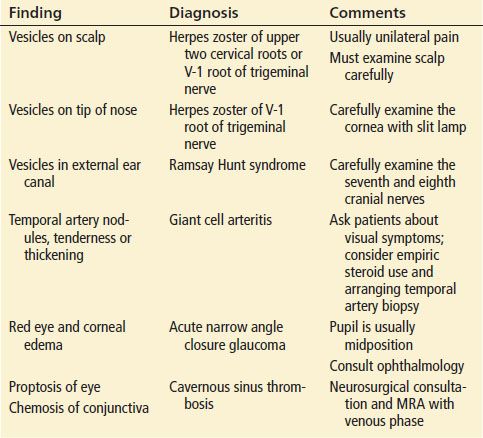

The HEENT examination may reveal the headache’s cause (Table 12.3). Vesicles on the scalp, tip of the nose, or external ear canal suggest herpes zoster. Scalp lesions suggest a first or second cervical root involvement; tip of the nose lesions suggest that the first division of the trigeminal nerve is involved and should prompt a careful slit-lamp examination to detect corneal involvement. Vesicles in the ear canal are associated with the Ramsay Hunt syndrome (herpes zoster infection causing seventh nerve palsy). Temporal artery tenderness, nodularity, or thickening is seen with giant cell arteritis. A red eye with an edematous cornea and midposition pupil suggests narrow angle closure glaucoma. Proptosis or chemosis suggests a cavernous sinus thrombosis.

TABLE 12.3

Common HEENT Findings that Suggest Particular Diagnoses