He Rnias

Jennifer M. DiCocco

Steven P. Goldberg

Timothy C. Fabian

I. Introduction

Hernia repairs are one of the most common operations performed.

An estimated 20 million hernia repairs occur each year worldwide. Of those, 5% to 15% are repaired emergently.

About 10% of hernia repairs are for recurrence.

Hernias site frequency (highest to lowest) is inguinal, umbilical, epigastric, incisional, femoral, and finally other rare types of hernias.

II. Abdominal Wall Anatomy

Hernias occur in areas of weakness or openings within the fascia, often where nerves, blood vessels, or gonadal structures penetrate the fascia.

The abdominal wall is created by layers of muscle and fascia.

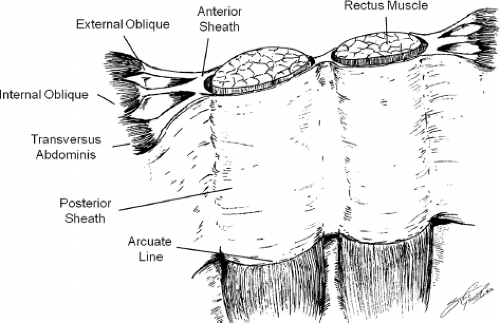

The rectus muscle is in the midline and surrounded by the anterior and posterior fascia (Fig. 56-1).

The external oblique contributes to the anterior rectus fascia while the internal oblique splits and contributes to both the anterior and posterior fascia superiorly.

At the level of the arcuate line, the entire internal oblique fascia courses anteriorly.

The transversus abdominis contributes to the posterior sheath to the level of the arcuate line.

Only the peritoneum covers the posterior rectus muscle caudad to the arcuate line.

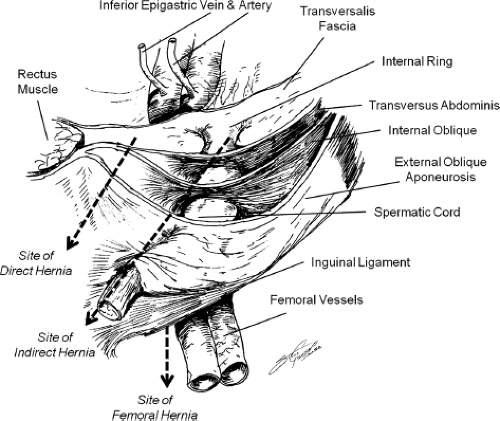

The inguinal canal contains the ilioinguinal nerve, the genital branch of the genitofemoral nerve and the round ligament in females or the spermatic cord in males (Fig. 56-2).

The roof of the canal is internal oblique and transversus abdominis muscles.

The floor is created by the inguinal ligament.

Anteriorly, the canal is formed by the external oblique aponeurosis

Posteriorly, the canal is formed by transversalis fascia and the conjoint tendon.

The superficial or external inguinal ring is formed by the external oblique fascia.

The deep or internal inguinal ring is located approximately halfway between the anterior superior iliac spine and the pubic tubercle. The deep ring is created by the transversalis fascia.

III. Presentation of Hernias

Symptoms. Can range from none to sepsis from obstruction with strangulation.

Most hernias present as a bulge on the abdominal wall with associated discomfort or pain. The bulge can be accentuated by having the patient increase intra-abdominal pressure through a Valsalva maneuver.

Patients with incarceration or strangulation may have findings of bowel obstruction, including nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, distension, constipation, or obstipation.

Figure 56-2. Inguinal anatomy and location of groin hernias. Sites of direct, indirect, and femoral hernias are shown.

Look for a hernia in any patient with a suspected bowel obstruction, as this is the most common cause of obstruction worldwide and the second most common cause of obstruction in the United States (after adhesive disease).

If strangulation and bowel necrosis is present, patients may be toxic appearing, febrile, and have peritonitis.

IV. Diagnosis

History and physical examination is diagnostic for most types of hernias. Examine patients both standing and supine, as the defect may become more obvious in one of the positions. Evaluate the entire abdomen, as some patients have multiple hernias.

Radiologic studies. If the patient history is consistent with a hernia, but a defect is not appreciated on physical examination, various radiologic modalities can be beneficial.

Plain films of the abdomen are useful when bowel obstruction is suspected; otherwise have little role.

Computed tomography is useful when a patient presents with abdominal pain and multiple causes are suspected. This modality gives the benefit of being able to evaluate other intra-abdominal organs and etiologies for abdominal pain.

Ultrasound can aid, especially in distinguishing scrotal hernias from hydroceles.

V. Complications

There are three main complications of all types of hernias: Incarceration, obstruction, and strangulation.

Incarceration occurs when abdominal contents are present within a hernia sac and cannot be reduced back into the abdomen.

The risk of incarceration is approximately 4 per 1,000 patients per year for groin hernias.

Obstruction occurs when intestine is present within the hernia sac and leads to a mechanical blockage. This may present as an acute or chronic obstruction, and partial or complete obstruction.

Strangulation occurs when a hernia is incarcerated and the blood supply becomes compromised leading to ischemia and necrosis of the incarcerated organ.

The pathogenesis of strangulation is incarceration leading to bowel wall edema followed by venous congestion which further increases the edema, eventually resulting in arterial compromise. This ultimately results in bowel ischemia, necrosis, and perforation.

Strangulation often requires bowel resection and is associated with increased morbidity and mortality.

VI. Management

Most hernias can be repaired electively. Incarcerated hernias should be repaired emergently if they cannot be reduced or if strangulation is suspected.

Patients with major medical comorbidities may receive nonoperative management. The risk and benefit of operation versus observation must be carefully considered. The signs and symptoms of incarceration and strangulation must be explained. The morbidity and mortality associated with an emergent repair is higher, especially if the incarcerated bowel becomes necrotic.

Recent data suggests that asymptomatic inguinal hernias in patients under 50 years old may be treated with “watchful waiting,” as the risk of incarceration is as low (1.8 per 1,000 patients per year in that population.)

For patients who present with incarcerated hernias, attempt gentle manual reduction.

If the hernia can be reduced, the repair can happen then or on an elective basis.

If a patient has local signs of ischemic intestine such as cellulitis, or abdominal findings consistent with strangulation such as peritonitis, do not try reduction. An infarcted segment of intestine may go unrecognized when reduced into the peritoneal cavity or preperitoneal space (reduction en-masse). Emergent surgical intervention is required.

VII. Specific Hernias

Inguinal hernia

Incidence. Lifetime risk of inguinal hernias for men is approximately 27% compared to 3% for females. There is also a slight right-sided predominance of inguinal hernias.

Anatomy. There are two basic types of inguinal hernias: Direct and indirect (Fig. 56-2).

Indirect inguinal hernias are more common and may extend down into the scrotum. These hernias are lateral to the inferior epigastric vessels and enter the inguinal canal through the deep ring.

Direct inguinal hernias are medial to the inferior epigastric vessels and enter through a weakening in the floor of the inguinal canal.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree