Hanging and Strangulation Injuries

Leon D. Sanchez and Richard E. Wolfe

Strangulation occurs when pressure is applied to the neck. This common injury accounts for 2.5% of traumatic deaths worldwide. Men are three to five times more likely to be victims than women, and those injured are most often between the ages of 21 to 40 (1). Causes of death from strangulation have been attributed to asphyxia, arterial occlusion, spinal cord injuries, and cardiac arrest due to pressure on the vasoactive centers of the great vessels. The specific role played by each of these causes as well as the types of injuries depend on the method used to apply pressure, the force, and the duration of the strangulation. To better manage this injury, it is helpful to subdivide strangulation by the methods used to apply the pressure: hanging, garroting, or throttling.

Hanging occurs when the ligature pressure is applied by the weight of the individual’s body as part of a judicial, homicidal, suicidal, or accidental event. Although judicial hangings are rarely performed today, hanging is the third most common form of suicide after firearms and ingestions. Men attempt hanging three times more often than women do. Newly jailed prisoners are at particular risk. Complete hanging refers to the body being suspended, and incomplete hanging describes situations where the body exerts pressure but is not suspended. Accidental hangings are most commonly incomplete. Children and individuals who practice autoerotic asphyxiation are the most common victims of accidental hanging (1).

Garroting or ligature strangulation involves pressure being applied to the neck by a ligature just as in hanging. The difference is that the force used to exert this pressure is something other than the individual’s body weight. Throttling can be considered a type of garroting where the ligature is the assailant’s hands, which exert the pressure directly.

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

Hanging or strangulation may result in injury to vascular structures in the neck. Venous obstruction results from forces applied to the jugular system (2,3). This leads to vascular congestion and cerebral hypoxia. As a result of the hypoxia, the neck musculature is thought to relax, leading to further compression that can lead to arterial and airway occlusion (2). Injury to the arteries is caused by hyperextension and rotation of the head. The carotid artery can be stretched over the transverse process of C2 or compressed by direct pressure over the transverse process of C6 (2,4). This can result in an intimal tear (4,5). Vertebral artery flow is not affected by direct pressure except at the extremes of rotation and lateral flexion (2).

Neurologic injury after hanging results from decreases in ventilation and cerebral perfusion. Autonomic stimulation from pressure on the carotid bodies or vagal sheath can lead to cardiac arrest (3,6). Hypoxia secondary to upper-airway obstruction plays a role in the development of neurologic injury or death but is thought to be second in importance to ischemia. Ischemic injury is caused by venous vascular congestion and arterial compression, both of which result in decreased cerebral flow (3,7–9). Increased intracranial pressure (ICP) secondary to cerebral edema is common in patients with altered mental status (10,11). Nevertheless, delayed neurologic sequelae are rare, and even patients who present with a low Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) often recover fully (3,8,9).

Injury to the laryngotracheal apparatus may be caused by compression or traction of the involved structures. Manifestations of these injuries may not be evident at presentation (12). Most airway injuries by themselves are not life threatening (3). In one study that looked at 112 deaths and 59 survivors of strangulation, only one case required emergent operative management (13). None of the deaths could be attributed to airway injury (13). Fractures of the hyoid bone and thyroid cartilage are seen with some regularity, whereas cricoid fractures are less common (13,14). The incidence of these fractures increases with greater age of the patient, probably due to calcification of the structures (14). Throttling victims have a much higher incidence of fractures as compared to hanging victims. The incidence of thyroid and hyoid fractures in hanging victims ranges from 10% to 15%; cricoid fractures are rare. Throttling victims have an incidence of fractures ranging from 30% to 40% (3,13,14). Even with the higher rates of injury in throttling victims, injuries to the laryngotracheal apparatus are rarely life threatening. Asphyxia from upper-airway obstruction due to the ligature itself is also rare, although pressure from the ligature can displace the tongue upward and obstruct the airway (6,9).

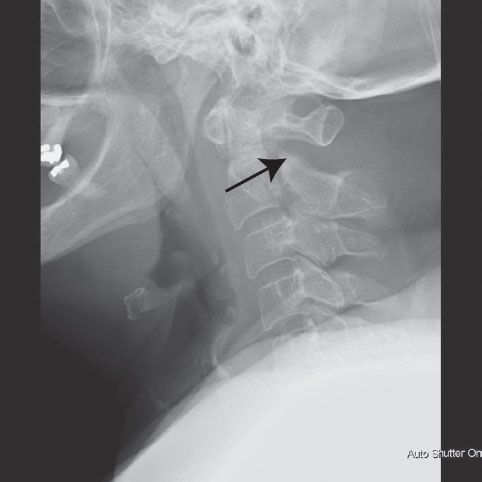

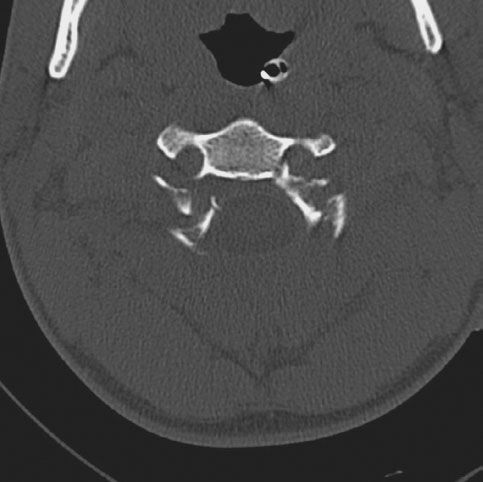

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, British postmortem studies of judicial hangings demonstrated that a minimum drop force (patient weight multiplied by the length of the drop) was needed to cause a cervical spine fracture. The required drop height varies depending on factors such as the weight of the subject, the neck musculature, and the strength of the bone itself. Although generally a drop height greater than the patient’s height is required to cause a spinal fracture, in rare circumstances shorter drop heights can produce these injuries. The minimum reported drop height is 3 ft (15,16). The most common spinal injury with long drops is disjointing of the second from the third cervical vertebra and bilateral fractures of the second cervical vertebra, the classic hangman’s fracture (Figs. 51.1 and 51.2). The position of the knot is important.

FIGURE 51.1 Lateral radiograph of cervical spine. Fracture of the posterior elements of C2 is indicated by the arrow. (Image courtesy of Marc Camacho, MD.)

FIGURE 51.2 Axial image of computed tomogram of C2 showing bilateral pedicle fractures. (Image courtesy of Marc Camacho, MD.)

In typical (nonjudicial) hangings, the knot is placed under the occiput and has the greatest ability to cause arterial occlusion rather than a spinal fracture. A hangman’s fracture will most likely occur when the knot is placed under the chin (submental) to ensure hyperextension, yet many judicial hangings were performed with the knot on the side of the jaw (subaural) which was less likely to result in a spine fracture and cord transection (17,18). Despite drops from body height and knot placement under the chin, even “proper” judicial hangings do not always cause cervical spine fractures (14,17,19). In complete suicidal and accidental hangings, most victims have negligible drop distances, and few sustain cervical spine fractures (7,9,16,20).

Pulmonary complications from strangulation injury include pulmonary edema, aspiration pneumonia, and the adult respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). Pulmonary edema is thought to be caused by markedly increased pulmonary transvenous pressures from forced inspiratory efforts against an occluded upper airway (21). Aspiration pneumonia in patients with a depressed mental status is reported in case series of strangulation victims (3,9,10). The ARDS in strangulation victims is secondary to brain hypoxia (22). Brain hypoxia leads to autonomic mediated vasoconstriction of the pulmonary venules, leading to ARDS and possibly contributing to pulmonary edema (22,23).

The clinical presentation of a patient with a strangulation injury can vary widely. The presenting mental status and GCS are related to the duration of hanging. The GCS is a poor predictor of the patient’s final outcome, and patients presenting with very low scores have a strong likelihood of surviving the injury with a normal mental status. Ligature marks are often, but not always, present (9). Subconjunctival, gingival, and oral petechial hemorrhages may be observed. These are thought to be caused by vascular congestion (13). Patients may also present with hoarseness or voice change (6), both of which may represent injury to the laryngotracheal apparatus. Subcutaneous emphysema can also be present (13). Occasionally, patients will present with frank stridor. Tachypnea can be an early sign of aspiration pneumonia or pulmonary edema (6,21).

Mental status changes may be secondary to brain anoxia, preexisting mental illness, or posttraumatic response to the event (6,9). In many of these patients, the evaluation may be more difficult owing to the presence of alcohol or other substances (6). One study found that 70% of hanging patients had concomitant drug or alcohol ingestion (16). Throttling victims often present after a domestic abuse incident and frequently will not volunteer the fact that they were throttled unless specifically asked (24).

ED EVALUATION

After immediate life-threats have been addressed, a more extensive history and physical examination should be performed. The presence of alcohol and other substances in these patients is common and may complicate the examination. In alert patients, attention should be paid to the evaluation of the laryngotracheal apparatus and to the pulmonary status. The presence of hoarseness, difficulty in swallowing, or other complaints that raise suspicion for laryngotracheal injury should prompt a more extensive workup. Although relatively rare, studies have shown an incidence of cervical spine fractures after suicidal near-hanging that may be as high as 7% (11,25). Imaging of the cervical spine may thus be indicated in the emergency evaluation of these patients and may reveal soft tissue swelling or a hyoid bone fracture. Evidence of laryngeal edema should be followed by prompt otolaryngology consultation. Computed tomography (CT) of the neck can be very helpful in delineating an injury to the laryngeal skeleton. Early control of the airway should be considered in these patients.

Pulmonary complications are the leading cause of death in patients who survive to hospital admission. Pulse oximetry and chest radiographs should be routinely performed in these patients. Manifestations of pulmonary edema and ARDS may be delayed by several hours. Aspiration pneumonia is also common and more likely in those patients with a depressed mental status.

Vascular injuries that are clinically significant are essentially restricted to the arterial tree. Although extremely rare, clinical signs of arterial dissection should prompt further workup. The most common signs that should raise suspicion for dissection are neurologic abnormalities consistent with a transient ischemic attack or cerebrovascular accident, Horner syndrome, amaurosis fugax, unexplained nausea or vomiting, and vertigo. Headache and neck pain are also common presenting complaints, although they are nonspecific.

The gold standard for detection of vascular injuries is four-vessel angiography. Magnetic resonance angiography and CT angiography are reasonable alternatives if angiography is unavailable or if they are available faster than angiography, as they may help delineate the injury and expedite the workup. However, these “techniques” may miss injuries, and a negative MRI or CT result does not completely rule out the diagnosis. Doppler ultrasonography is not useful for the evaluation of the vertebral arteries but can provide useful information about the carotid arteries; however, the sensitivity of duplex ultrasound is not high enough to completely rule out carotid injury. In patients in whom there is a high suspicion for arterial injury, four-vessel angiography remains the test of choice. If unavailable, transfer of the patient to another institution should be considered.

KEY TESTING

• CXR to evaluate for pulmonary edema, ARDS, and aspiration pneumonia

• Cervical spine CT or plain films to evaluate for fracture. As angiography (CTA) may often be done CT/CTA may obviate need for plain films

• Angiography for vascular injuries (CTA, MRA, angiography)