INTRODUCTION

GYNECOLOGIC CONDITIONS: VAGINITIS

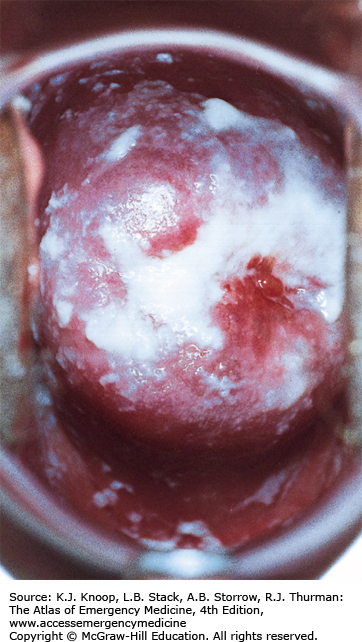

Candidal vaginitis is characterized by a thick, clumping, white discharge and vulvar discomfort. Intense vulvar erythema, pruritus, and/or burning are often present. Predisposing factors may include oral contraceptive, antibiotic, or corticosteroid use; pregnancy; and diabetes. A microscopic slide prepared with 10% potassium hydroxide yielding characteristic branched chain hyphae and spores establishes the diagnosis. Sexually transmitted diseases are not usually associated with isolated Candidal vaginitis.

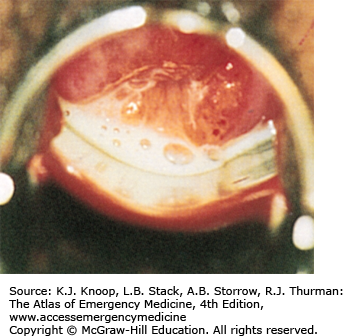

Trichomonas vaginitis presents as a persistent, thin, copious discharge that is often frothy, green, or foul-smelling. The amount of vaginal and cervical erythema and inflammation varies considerably. Diagnosis may be made by the presence of motile flagellates on normal saline wet-mount microscopy, but this is only 60% to 70% sensitive. New nucleic acid tests are emerging with ~95% specificity. Multiple petechiae on the vaginal wall or cervix (strawberry spots/strawberry cervix) are pathognomonic but only occasionally seen.

Bacterial vaginosis is characterized by a malodorous, homogeneous discharge with an amine (fishy) odor that can be briefly accentuated by mixing with a drop of KOH solution. The presence of clue cells on normal saline wet mount establishes the diagnosis. Other associated vaginal or abdominal complaints are minimal and, if significant, suggest the presence of another disease process.

Although the above infectious causes are responsible for most cases of vaginitis, other possible etiologies including local chemical irritants or allergens, vaginal foreign bodies, and atrophic vaginitis should be considered in the differential diagnosis.

For Candidal vaginitis, treat with topical antifungals (eg, clotrimazole: 1% cream, 5 g for 7 to 14 days or two 100-mg vaginal tablets for 3 nights). Oral fluconazole (150 mg as a single dose) is also effective, but has a higher risk of adverse effects.

For Trichomonas vaginitis, a single dose of metronidazole (2 g orally) is generally curative but is associated with a disulfiram-like reaction when taken with alcohol. Although metronidazole was previously considered contraindicated in pregnancy, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) now recommends its use due to the association of Trichomonas infections with preterm rupture of membranes, low birth weight, and increased risk of prematurity.

For bacterial vaginosis, metronidazole (500 mg orally twice daily for 7 days) is recommended. Treatment for asymptomatic infection or for male sexual partners is not generally recommended. The equivocal risk of metronidazole teratogenicity must be weighed against the likelihood of alleviating symptoms and discomfort.

Diabetes mellitus or immunosuppression should be considered in refractory or recurrent cases of candidal vaginitis.

A history of balanitis in the sexual partner should be sought and treated if present.

Trichomonas should be considered a sexually transmitted infection. Therefore, it is generally recommended that concomitant culturing for Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia be performed. Serologic testing for syphilis, HIV, and hepatitis B should also be considered for patient and partner.

| Disease | Discharge Qualities | Vaginal pH | Microscopic Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Candida spp. | White, thick, clumping | <4.5 | Hyphae and spores in KOH |

| Trichomonas vaginitis | Green, thin, frothy, foul | >4.5 | Flagellates in wet mount |

| Bacterial vaginosis | Thin, white, “fishy” odor in KOH | >4.5 | Clue cells |

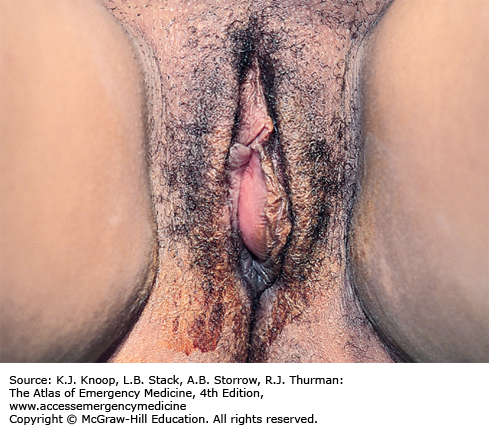

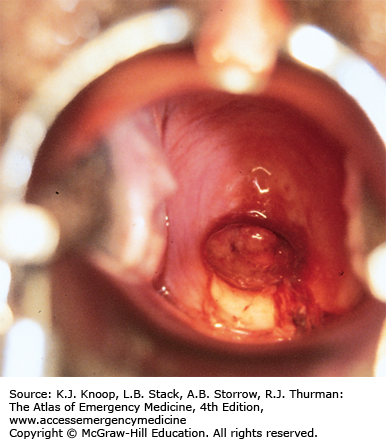

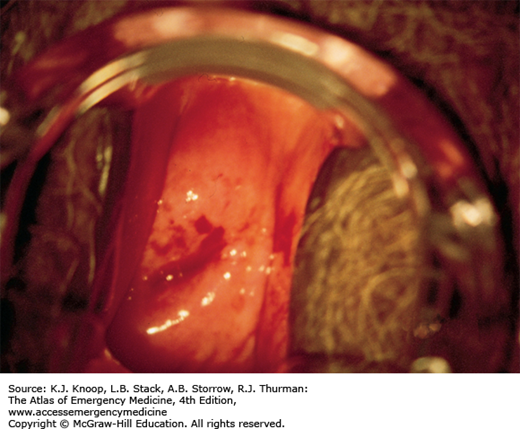

CERVICAL POLYPS

Cervical polyps are friable, fleshy, fingerlike growths that emanate from the cervical os or endocervical canal. They are typically asymptomatic, but may bleed with minimal trauma such as intercourse or douching. Single polyps are more common, but multiple polyps can occur. The etiology of polyps varies and may be related to infection, chronic inflammation, or excess estrogen.

No treatment is necessary in the emergency department (ED). Consider alternative causes of vaginal bleeding such as infection and pregnancy. Refer all patients with incidentally discovered polyps for outpatient gynecological evaluation.

The majority of cervical polyps are benign, but all should be referred for ligation and histologic evaluation.

Cervical polyps are the most common benign neoplasm of the cervix.

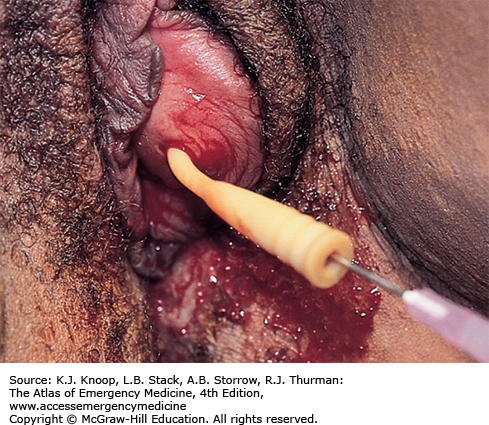

BARTHOLIN GLAND ABSCESS

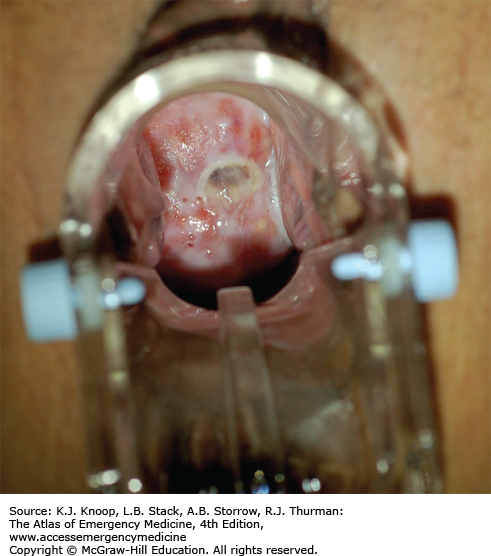

Bartholin glands are located on either side of the lower third of the vaginal introitus near the labia minora. A cyst or abscess may result from an obstructed duct, often secondary to trauma or inflammation. Infection of the cyst is usually with mixed vaginal or fecal flora (Escherichia coli) but may also contain N gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia trachomatis. Cysts or abscesses may be asymptomatic or may lead to increasing pain, swelling, and dyspareunia. A tender, fluctuant cystic mass with surrounding labial edema is easily appreciated on examination. Differential should include epidermal inclusion cysts and sebaceous cysts of the labia majora, hidradenitis suppurativa, vulvar hematomas, leiomyomas, lipomas, and fibromas.

Simple incision and drainage followed by sitz baths is the most effective immediate treatment, but recurrence of cysts is common with this method. Placement of a Word catheter into the cyst cavity decreases the incidence of reocclusion. The catheter, however, must remain in place up to 6 weeks to ensure epithelialization.

Antibiotics are usually not required.

Incise the internal (medial) surface of the cyst or abscess rather than the external (lateral) aspect, as the incision site may become the new drainage tract.

Refer recurrent abscesses to gynecologist for definitive treatment which may involve marsupialization of the gland.

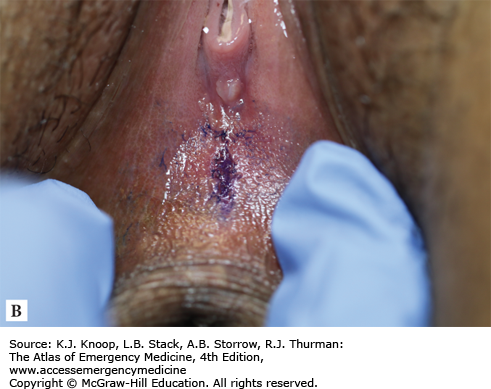

FIGURE 10.10

Bartholin Gland Abscess. Insertion and inflation of a Word catheter into the cyst cavity. The free end of the catheter can be tucked into the vagina for long-term placement, allowing for epithelialization of the incision site. (Photo contributor: Medical Photography Department, Naval Medical Center, San Diego, CA.)

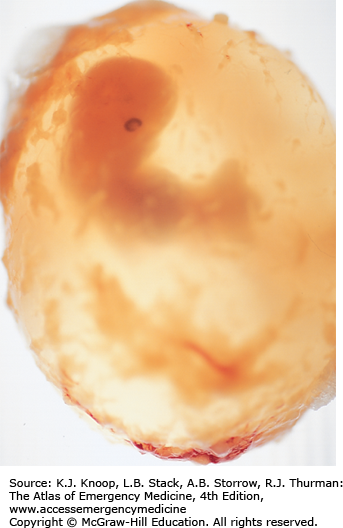

SPONTANEOUS ABORTION

Spontaneous abortion is associated with vaginal bleeding and abdominal discomfort. Severe pain, heavy bleeding, passage of clots or tissue, and hypotension may also be present. Mild cramping and vaginal bleeding that are not accompanied by passage of tissue or cervical dilation constitutes a threatened abortion. Uterine cramping with progressive cervical dilation indicates an inevitable abortion. An incomplete abortion is diagnosed when some products of conception (POC) have passed, while other retained intrauterine tissue leads to ongoing symptoms. Fever, leukocytosis, pelvic tenderness, and malodorous cervical discharge suggest a septic abortion. Completed abortion is characterized by the passage of confirmed POC, followed by resolution of bleeding and closure of the cervical os. Large blood clots or intrauterine decidual casts may be mistaken for POC and their presence cannot be used to rule out ectopic pregnancy.

Immediately obtain large-bore intravenous access and institute aggressive fluid resuscitation for any patient with severe pain, heavy bleeding, or hypovolemia. Also request cross-matched blood and urgent gynecologic consultation. Stable patients can undergo routine ED evaluation with complete blood count (CBC), human chorionic gonadotrophin (hCG), pelvic exam, and ultrasound (US). Send all identified tissue to pathology for definitive identification. Ectopic pregnancy must be ruled out by US, close clinical follow-up, and serial hCG testing. Administer anti-Rh immunoglobulin (RhoGAM) in all cases of vaginal bleeding where the mother is Rh-negative.

The passage of large clots usually indicates rapid heavy bleeding.

Heterotopic pregnancy is rare, but should be considered in patients with significant ongoing symptoms despite identification of a viable early intrauterine pregnancy (IUP).

Septic abortion may extend to the surrounding tissues or blood, with the potential for septic shock, ARDS, DIC, and group A strep induced toxic shock syndrome.

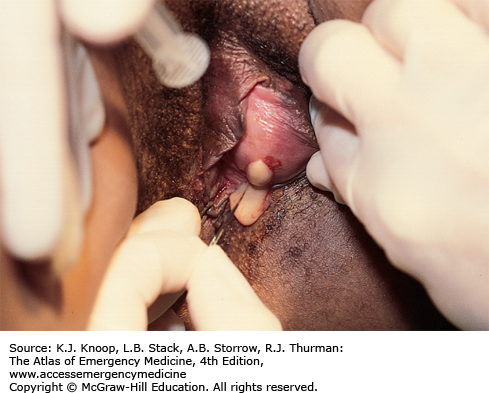

GENITAL TRAUMA AND SEXUAL ASSAULT

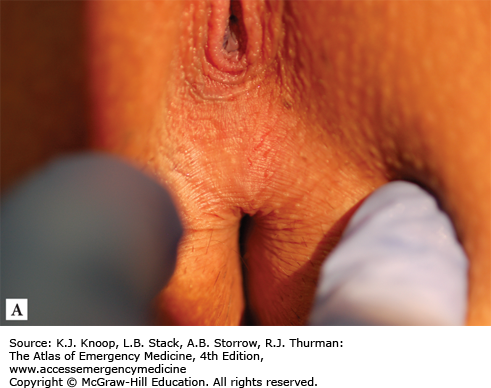

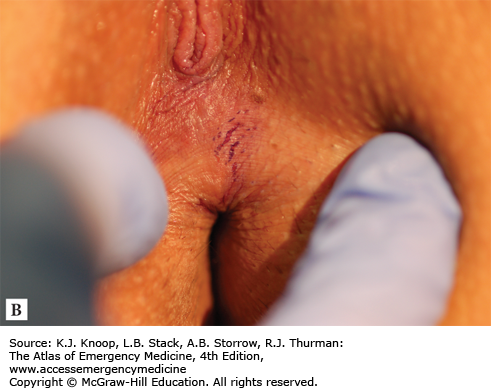

In cases of sexual assault, immediate care for the acute medical and psychosocial needs of the patient must happen in concert with forensic and legal requirements. Ideally, this care is provided by a specially trained sexual assault examiner. Regardless of who performs the examination, the provider must be very thorough in collecting and preserving all potential evidence and carefully documenting any physical findings. Chain of custody must be established and maintained for all samples collected in order for them to be used in later legal proceedings. Meticulous inspection of the genital structures in addition to a thorough general physical examination may reveal injuries to the perineum, rectum, vaginal fornices, vagina, and cervix as well as associated injuries to other areas of the body. Toluidine staining and colposcopy are useful in enhancing less apparent injuries such as those to the posterior fourchette and perianal area. Tears to the posterior fourchette are most commonly found in the distribution between the 3- and 9-o’clock positions when the patient is examined in dorsal lithotomy. Perianal lacerations are more evident with toluidine staining and appear as linear tears. Perineal injuries from accidental trauma may be indistinguishable from those of sexual assault and should be interpreted in the context of the history.

Treatment other than pain relief is preceded by forensic evidence gathering, consisting of a Wood lamp examination to identify semen for collection, pubic hair sampling and combing, vaginal and cervical smears (air-dried), a cervical and vaginal wet mount to identify sperm, vaginal aspirate to test for acid phosphatase, and rectal or buccal swabs for sperm. A prepackaged kit with directions may be available to facilitate the collection of evidence. Consult your state’s laws for requirements.

Obtain cervical cultures for Chlamydia and N gonorrhoeae as well as serum testing for syphilis, hepatitis, and HIV. Provide empiric antibiotic coverage against sexually transmitted diseases and offer an oral contraceptive to prevent unwanted pregnancy after confirming a nonpregnant state.

Victims of sexual assault may initially be reluctant to disclose their history and often present with an unrelated chief complaint. A thorough sexual history is necessary in order to properly identify and treat them.

The medical care of the patient who has been sexually assaulted is ideally performed by experienced supportive staff familiar with the details of forensic evidence gathering and colposcopic photography.

Normal physical examination and lack of sperm on wet preparation do not exclude the possibility of assault.

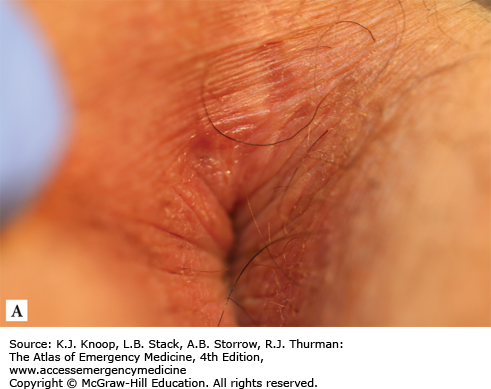

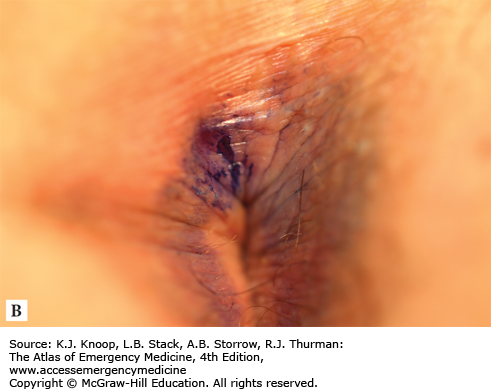

FIGURE 10.18

Anal Trauma (Perianal, Toluidine Blue). Multiple perianal tears without toluidine blue stain (A) and with stain (B). Note specific stain uptake enhancing two tears at 11-o’clock position in contrast to nonspecific uptake elsewhere. (Photo contributors: Hillary J. Larkin, PA-C, and Josua Luftig, PA-C.)

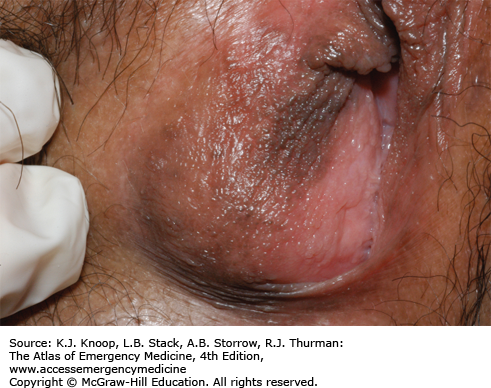

LICHEN SCLEROSUS

Lichen sclerosus (LS) is a benign, chronic, inflammatory condition that results in epithelial atrophy or hyperplasia, and scarring. The condition typically occurs in the anogenital region (85-98%), but can develop on any skin surface. Women are affected 10 times more often than men and onset is often perimenopausal. The etiology is unknown, but it is seen more commonly in individuals with autoimmune conditions such as diabetes mellitus type 1, vitiligo, and thyroid disorders in women in a low estrogen state, suggesting that these may be contributing factors.

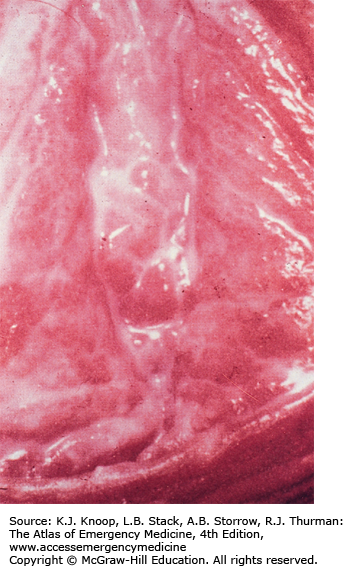

Patients may be asymptomatic or may have intense pruritis and pain in the affected areas. Other symptoms may include bleeding, dyspareunia, or dysuria. Lesions appear as white, atrophic papules and patches and most often affect the labia minora and/or labia majora. Excoriations may be present and scratching may lead to secondary lichenification (thickening of the epidermis with exaggeration of normal skin lines). As the disease progresses, scarring may lead to loss of the vulvar architecture with fusion of the labia. The vagina and cervix are not involved. Extragenital lesions may occur on the thighs, breasts, wrists, shoulders, neck, and, rarely, the oral cavity. These lesions also consist of white papules or plaques and are not as pruritic as genital lesions.

No treatment is necessary. Potent topical steroids, hormonal treatments, and/or immunosuppressants may benefit. Advise patients on good vulvar hygiene cessation of scratching to prevent secondary infections. Consider oral antihistamines for pruritis. Refer patients for outpatient gynecological evaluation. Definitive diagnosis is made by biopsy.

LS is associated with an increased risk of vulvar squamous cell cancer. Refer all patients for biopsy and histologic evaluation.

Although LS is not an infectious condition, the presence of open excoriations and fissures can increase risk of acquiring sexually transmitted infections.

LICHEN PLANUS

Lichen planus is a chronic inflammatory condition that can affect any area of skin, mucosa, nails, and scalp. Vulvar involvement is found in 50% of women with lichen planus. The etiology is unknown, but may be autoimmune as the disorder is often associated with other autoimmune diseases.

Affected women may complain of intense vulvar pruritus, pain, and/or dysuria. Vaginal involvement is seen in 70% of cases and may cause vaginal discharge, dyspareunia, and occasionally postcoital bleeding. Coexisting oral or other cutaneous lesions are common. On examination, vulvar lichen planus is characterized by glassy, erosive, or papular lesions. Desquamation may be present. Recurrent lesions may lead to extensive scarring with resultant loss of the vulvar architecture including stenosis of the vaginal introitus and urethral obstruction.

Lichenoid drug eruptions can be clinically indistinguishable from lichen planus. Use of specific medications including β-blockers, methyldopa, penicillamine, quinidine, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), angiotensin-converting-enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, sulfonylurea agents, carbamazepine, gold, lithium, quinidine, or hydrochlorothiazide (HCTZ) has been associated with lichenoid drug eruptions.

No treatment is necessary in the ED. Potent topical steroids are first-line treatment. Sitz baths may help alleviate symptoms. Advise patients on good vulvar hygiene including cessation of scratching to prevent secondary infections. Consider oral antihistamines for pruritis. Discontinue any medications that may be associated with a lichenoid drug eruption. Refer all patients for outpatient gynecological evaluation. Definitive diagnosis is made by biopsy.

HCTZ and NSAIDs are common triggers for recurrent lichen planus. Discontinuation of these medications may improve symptoms.

Lichen planus does not involve the perianal region.