Acute

Testicular torsion

Infectious (epididymo-orchitis)

Torsion of the appendix testis

Fournier’s gangrene

Nephrolithiasis

Chronic

Testicular masses

Chronic pelvic pain syndrome/chronic scrotal pain syndrome

Infectious (epididymitis/prostatitis)

Varicocele

Hydrocele

Epididymal cysts/spermatocele

Post-vasectomy pain syndrome

While there are many identifiable causes, groin pain of unclear etiology is often given the nonspecific diagnosis of chronic epididymitis. But with better understanding of pelvic floor anatomy, there has been a concerted effort toward a more nuanced approach to chronic groin pain, or more expansively, CPPS. In 2010, the European Association of Urology (EAU) released guidelines that broadly defines chronic pelvic pain as nonmalignant pain perceived in pelvic structures that is present in a continuous or recurrent fashion for at least 6 months, with the caveat that if non-acute and central sensitization pain mechanisms are well documented the pain can be considered chronic irrelevant of time period [2]. Chronic scrotal pain syndrome is a subset of CPPS characterized by persistent or episodic scrotal pain with symptoms suggestive of urinary tract or sexual dysfunction [2]. The EAU classification system of chronic urogenital pain syndromes is shown in Table 10.2.

Table 10.2.

European Association of Urology classification of chronic pelvic pain syndromes.

Axis I Region | Axis II System | Axis III End-organ as pain syndrome as identified from Hx, Ex, and Ix | Axis IV Referral characteristics | Axis V Temporal characteristics | Axis VI Character | Axis VII Associated symptoms | Axis VIII Psychological symptoms | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Chronic pelvic pain | Specific disease-associated pelvic pain OR Pelvic pain syndrome | Urological Gynecological Gastrointestinal | Prostate Bladder Scrotal Testicular Epididymal Penile Urethral Post-vasectomy Vulvar Vestibular Clitoral Endometriosis-associated Chronic pelvic pain syndrome with cyclical exacerbations Dysmenorrhea Irritable bowel Chronic anal Intermittent chronic anal | Suprapubic Inguinal Urethral Penile/clitoral Perineal Rectal Back Buttocks Thighs | Onset Acute Chronic Ongoing Sporadic Cyclical Continuous Time Filling Emptying Immediate post Late post Trigger Provoked Spontaneous | Aching Burning Stabbing Electric | Urological Frequency Nocturia Hesitance Dysfunctional flow Urge Incontinence Gynecological Menstrual Menopause Gastrointestinal Constipation Diarrhea Bloatedness Urge Incontinence Neurological Dysaesthesia Hyperaesthesia | Anxiety About pain or putative cause of pain Catastrophic thinking about pain Depression Attributed to pain or impact of pain Attributed to other causes Unattributed PTSD symptoms Reexperiencing Avoidance |

Peripheral nerves Sexological | Pudendal pain syndrome Dyspareunia Pelvic pain with sexual dysfunction Any pelvic organ Pelvic floor muscle Abdominal muscle Spinal Coccyx | Allodynia Hyperalgesia Sexological Satisfaction Female dyspareunia Sexual avoidance Erectile dysfunction Medication Muscle Function impairment Fasciculation Cutaneous Trophic changes Sensory changes | ||||||

Psychological | ||||||||

Musculoskeletal | ||||||||

Epidemiology

The true incidence of chronic groin pain in the general population is difficult to assess. Bartoletti et al. found the prevalence and incidence of CPPS in men aged 25–50 years to be 13.8 % and 4.5 %, respectively, with 18 % of those patients already diagnosed with chronic scrotal pain [3]. The prevalence of chronic epididymitis in men visiting urology clinics in Canada was estimated to be about 0.9 % [4]. In 2005, Strebel et al. found that urologists had an average of 6.5 new encounters for chronic scrotal pain per month, and 2.5 % of all urological visits led to a diagnosis of chronic scrotal pain syndrome [5]. The incidence of chronic scrotal pain was estimated to be about 350–450 per 100,000 men aged 25–85 years [5]. Multiple publications have reported the peak age of chronic pelvic pain in their cohort to be at ages 40–49, with range from 20 to 83 [6–10]; however, these numbers were based on trials of men seeking interventions for chronic pain, and not direct epidemiological measurements.

Anatomy

Testicular pain is mediated by scrotal and spermatic branches of the genitofemoral and ilioinguinal nerves, as well as by sympathetic fibers along the testicular artery [8]. The genital branch of the genitofemoral nerve supplies the cremaster muscle and scrotal skin, and a branch of the ilioinguinal nerve supplies the skin of the upper scrotum and base of the penis. There is significant sensory overlap among the ilioinguinal , iliohypogastric , and genitofemoral nerves [11]. The course of the nerves through the inguinal canal can be seen in Fig. 10.1 [12]. Spermatic cord traction during scrotal surgery may trigger peritoneal stimulation [13]. The superior and inferior spermatic nerves provide autonomic innervation [14]. The superior spermatic nerve originates from the celiac and aortic plexuses and descends along the testicular vessels and forms the major nerve supply of the testis [14]. Sympathetic fibers arise from the thoracic segments 10 and 11, whereas the parasympathetic fibers arise from the vagus nerve [14]. The inferior spermatic nerve travels with the ductus deferens and the epididymis to the lower pole of the testis [14]. Sympathetic fibers arise from the inferior mesenteric and hypogastric plexuses and parasympathetic fibers branch from the pelvic nerve [14]. Animal models indicate that the nerve supply to the testis helps to regulate its endocrine function, but the precise function of testicular innervation in humans remains unclear. Epididymal innervation consists of a high density of sympathetic nerve endings in the corpus and cauda of the epididymis, with progressive concentration approaching the ductus deferens, consistent with their contractile role during ejaculation [15].

Fig. 10.1.

Pelvic nerves in relationship to the inguinal canal. Note the location of the genital branch of the genitofemoral nerve, ilioinguinal nerve, and iliohypogastric nerve as they travel through the inguinal ring (redrawn from Kapoor et al. [12] with kind permission of Medscape Reference from WebMD).

Acute Groin Pain

Although the focus of this chapter is spermatic cord and testicular causes of chronic groin pain, a review of acute groin pain highlights the range and complexity of pain in this region. Men with acute scrotal pain must be quickly triaged to identify those who need immediate surgical intervention, as a delayed diagnosis may result in significant morbidity and even mortality.

Testicular Torsion

Testicular torsion must be suspected in a man presenting with sudden onset unilateral pain without a history of trauma, often accompanied by nausea and vomiting. This may be seen after an open inguinal hernia repair, especially if the hernia had scrotal extension of its contents. During the operative manipulation, the testicle may be raised into the operative field, i.e., the groin incision, and returning the testicle back down into the scrotum may initiate the torsion. The window of time to save the testis is 4–8 h [16]. Physical exam findings include scrotal edema, erythema, and exquisite diffuse tenderness over the testis. Pain localized over the epididymis may be due to epididymitis or torsion of the appendix testis. Although the cremasteric reflex is often absent in testicular torsion, the presence of the reflex does not rule out torsion [17]. Ultrasound is helpful in the diagnosis of testicular torsion, with specificity approaching 100 % [18, 19]. If suspicion for torsion is high, surgical exploration should proceed without need for ultrasonic verification [20]. Surgery involves either orchiopexy or orchiectomy of the affected testis and orchiopexy of the contralateral testis if it was a spontaneous torsion.

Fournier’s Gangrene

Fournier’s gangrene is an infected, necrotizing fasciitis of the perineal, genital, or perianal regions [21]. Patients present with local discomfort associated with erythema, swelling, and crepitus. Abnormal vital signs and metabolic derangements predict worse prognosis and higher mortality risk [22]. Fournier’s gangrene is a clinical diagnosis, requiring emergent surgical intervention if suspicion is high [23]. CT scan may demonstrate subcutaneous emphysema along fascial planes in the scrotum, perineum, and inguinal regions [24]. Treatment includes aggressive fluid resuscitation, broad-spectrum antibiotics, and early extensive debridement of the involved fascial planes [25]. The mortality of Fournier’s gangrene even with appropriate treatment is high, approaching 15–40 % [23, 26, 27].

Torsion of the Appendix Testis

One of the most common causes of acute scrotal pain in the pediatric population is torsion of the appendix testis. Torsion of the appendix testis is a far more common cause of acute scrotal pain in boys than testicular torsion; one series showed that only 16 % of children presenting with testicular pain had torsion of the testicle as opposed to 46 % diagnosed with torsion of the appendix testis [20]. The appendix testis is a remnant of the Müllerian duct located on the upper pole of the testis. Differentiating torsion of the appendix testis from true testicular torsion can be challenging. Patients with torsion of the appendix testis may have a more insidious onset of pain over several days, with waxing and waning of pain levels. The “blue dot sign” of a palpable, infarcted appendix testis can be seen on exam in up to 21 % of patients [28]. Ultrasound can reliably identify torsion of the appendix testis and differentiate it from testicular torsion [29]. Treatment consists of rest and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) .

Acute Epididymitis

Acute epididymitis is an inflammation of the epididymis presenting acutely with pain and swelling. Objective findings of acute epididymitis include fever, scrotal erythema, leukocytosis on urinalysis, and positive urine culture. The pathophysiology is unclear but is thought to be secondary to retrograde flow of infection into the ejaculatory ducts [30]. In men under age 35 years, the most common etiology of acute epididymitis is sexually acquired Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae , while in men aged 35 years and over, the organisms that cause urinary tract infections (e.g., Gram-negative rods) are the predominant isolates [31, 32]. Men presenting with possible acute epididymitis should have a midstream urine collection along with Gram stain of a urethral smear, although empiric treatment should begin at the time of initial evaluation. Treatment involves bed rest, scrotal support, NSAIDs, and antibiotics.

Orchitis

Isolated acute orchitis is relatively rare, as it usually occurs by local spread of infection from the epididymis. Isolated orchitis often has a viral cause, with mumps being the most common etiology. Mumps orchitis is characterized by painful testicular swelling 4–8 days after the appearance of parotitis [33]. Orchitis develops in 15–30 % of men with mumps. Mumps orchitis is not common before puberty [34]. Mumps orchitis is associated with reduced testicular size in up to half of patients and with semen analysis abnormalities in about 25 % [35]. Treatment is largely supportive.

Nephrolithiasis

Nephrolithiasis is a common urological problem, with lifetime prevalence of approximately 10 % in men [36]. Although the classic presentation includes flank pain and hematuria, a stone impacted in the distal third of the ureter can cause referred pain to the groin. A stone should be considered in a patient who has groin pain associated hematuria, flank pain, or a history of nephrolithiasis. A non-contrast helical computed tomography (CT) scan is the preferred imaging study, with a specificity of 98 % and sensitivity of 95 % [37]. Spontaneous passage rates of stones are directly related to size: as high as 60 % for 5–7 mm stones and less than 25 % for stones larger than 9 mm [38]. If surgical intervention is indicated, ureteroscopy with laser lithotripsy results in a stone-free rate up to 96 % [39].

Chronic Groin Pain

Chronic pain, whether epididymal or testicular in origin, has been defined as symptoms of at least 3 months’ duration [1, 40]. Chronic pain may be of neuropathic origin. When a nerve is sensitized by repeated stimulation, pain can persist even after the initial insult has resolved. This “hard-wiring” is mediated by peripheral and central modulation that reduces the threshold for activation of the action potential and decreases response latency [11]. Reversible causes of chronic groin pain must be ruled out before diagnosing CPPS.

Testicular Mass

Testicular cancer is the most common cancer among men between ages 15 and 35 years—an age group that overlaps with that of chronic groin pain [41]. Although the majority present with a painless palpable testicular mass, some report a dull ache or heaviness in the scrotum or lower abdomen. Approximately 10 % of men with testicular cancer present with groin pain [42]. Ultrasound confirms the diagnosis, after which tumor markers are sent prior to prompt inguinal orchiectomy.

Conversely, an incidental impalpable testicular mass may be diagnosed during an evaluation for chronic groin pain. With increasingly finer resolution of ultrasound, masses as small as 1 mm can be detected long before they would be palpable [43]. Among men undergoing scrotal ultrasound for reasons other than for the evaluation of a retroperitoneal mass, Powell and Tarter found the incidence of testicular mass to be 0.38 % [44]. In men undergoing testicular ultrasound for infertility, the incidence of testicular tumors was 0.5 % [45]. Generally, the treatment of any sized testicular mass is radical orchiectomy, but some centers now perform excisional biopsies of small masses under 1 cm in diameter with the aid of an operating microscope, intraoperative ultrasound, and frozen section pathologic analysis. In one review, 19 of 49 cases of incidental testicular masses were found to be malignant [46].

Varicocele

Varicocele is a dilation of the pampiniform plexus of spermatic veins, which can result in a dull, aching scrotal pain [47]. Varicoceles affect 15 % of adolescent and adult men [48]. In men seeking treatment for infertility, the prevalence of varicoceles has been found to be as high as 40 % [49]. Varicoceles almost always occur on the left side or are bilateral. The pathophysiology of varicoceles is poorly understood. Anatomy may play a role, as the left gonadal vein drains into the higher pressure left renal vein at almost a 90° angle, as opposed to the right gonadal vein, which drains into the lower pressure inferior vena cava. The left gonadal vein is also longer, with fewer valves compared to the right gonadal vein [48].

Unilateral right-sided varicoceles raise concern for extrinsic compression of the gonadal vein by a retroperitoneal mass. Also, among patients who have undergone inguinal hernia repair, note that the scar tissue and/or the mesh implant may be causing the extrinsic compression resulting in secondary varicocele. In such cases, further imaging is indicated, and workup should be directed to the offending cause of the varicocele.

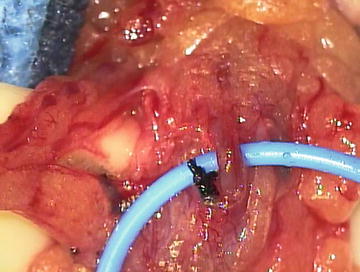

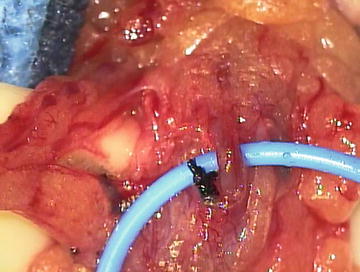

Varicocelectomy can be performed by the open or laparoscopic approach, but microsurgery remains the gold standard (Fig. 10.2) [50]. Because of the proximity of scrotal lymphatic channels to the ligated veins during varicocelectomy, hydrocele formation is a possible complication. The rates of postoperative hydrocele range from 0 to 1.2 % in the microsurgical group, 5–20 % in the laparoscopic group, and 6–15 % in the open group [51–54]. A recent meta-analysis of randomized trials comparing open, laparoscopic, and microsurgical varicocelectomy showed both the hydrocele formation and varicocele recurrence rates to be significantly lower in the microsurgical group [55]. The recurrence rate after microsurgical varicocelectomy is low, ranging from 0 to 2.5 %, compared to 7–16 % and 17–20 % in the open and laparoscopic groups, respectively [52, 53, 56].

Fig. 10.2.

Microsurgical varicocelectomy. The testicular artery is identified and isolated with a vessel loop, lymphatics channels are seen to the right of the artery and are preserved, and all venous structures are ligated with 4–0 silk or clips.

Hydrocele

A hydrocele is a fluid collection around the testis contained within the tunica vaginalis and is a common finding in both adults and children. Although usually asymptomatic, a large hydrocele can cause a pulling sensation on the scrotum and significant discomfort. Hydroceles are either communicating or noncommunicating, with the former more often seen in boys and the latter in men. Communicating hydroceles represent a patent processus vaginalis, while noncommunicating hydroceles result from an imbalance of fluid production and reabsorption. The incidence of acquired or noncommunicating hydrocele is estimated at about 1 % in men [57].

Pediatric hydrocelectomy is similar to a pediatric herniorrhaphy . A small inguinal incision is made, the spermatic cord is visualized, and the hernia sac is dissected off the cord, taking care not to injure the spermatic cord structures. High ligation of the hernia sac is recommended to prevent future recurrence [58].

The treatment of adult hydroceles is almost always through a scrotal incision, and a variety of techniques have been described [59]. At our institution, we commonly use the Jaboulay technique, which involves delivering the testis through a scrotal incision, excising the excess portion of the tunica vaginalis, and everting the remnant [60]. Communicating hydroceles in men, although rare, may be a sign of an underlying inguinal hernia. Hydroceles associated with hernias can be a cause of groin pain, and an inguinal exploration with herniorrhaphy is indicated.

Epididymal Causes of Chronic Scrotal Pain

Chronic epididymitis is a common cause of chronic scrotal pain . Nickel developed a classification system for chronic epididymitis (Table 10.3) [40]. Workup and treatment of chronic epididymitis is difficult because there is no identifiable cause in the majority of cases.

Table 10.3.

Classification of chronic epididymitis.

1.Inflammatory chronic epididymitis: pain and discomfort associated with abnormal swelling and induration |

a. Infective |

b. Post-infective (following acute bacterial epididymitis) |

c. Granulomatous (tuberculosis) |

d. Drug induced (amiodarone) |

e. Associated with syndromes (Behçet’s disease) |

f. Idiopathic |

2.Obstructive chronic epididymitis (i.e., congenital obstruction vs. post-vasectomy scarring) |

3.Chronic epididymalgia: pain or discomfort in a normal feeling epididymis with no identifiable etiology |

Granulomatous Epididymitis

Tuberculosis should be suspected in men presenting with chronic granulomatous epididymitis , especially if they have a known history or recent exposure. Those with tuberculosis epididymitis should have further evaluation for systemic disease along with treatment with 6 months of triple drug therapy of isoniazid, rifampin, and pyrazinamide [30]. Sarcoidosis is a less common cause of granulomatous epididymitis, with an estimated 0.2–5 % of cases having genitourinary involvement [30, 61].

Drug-Induced Epididymitis

The most common drug implicated in the development of epididymitis is the anti-arrhythmic amiodarone. While the exact mechanism is unknown, tissue levels of amiodarone and its metabolites have been shown to be 25–400 times higher in the epididymis than serum, which may lead to fibrosis and lymphocyte infiltration [62]. The incidence of amiodarone-induced epididymitis in men taking high-dose amiodarone is 3–11 %, with discontinuation of the drug generally leading to resolution of symptoms [63].

Idiopathic Chronic Epididymitis

In the absence of an identifiable cause of epididymal pain, the diagnosis of idiopathic chronic epididymitis is often made. Idiopathic inflammatory epididymitis involves focal epididymal tenderness with swelling and induration, whereas chronic epididymalgia involves referred epididymal pain as part of CPPS. In a cohort of 488 men evaluated for CPPS, 47 % had subjective symptoms of testicular pain, of whom only 7.5 % had reproducible tenderness [64], highlighting the importance of properly classifying patients with CPPS. The treatment of CPPS is discussed below, but patients with idiopathic inflammatory epididymitis are often treated with long-acting NSAIDs and rest [30]. If pain persists despite conservative management, surgical options such as microsurgical spermatic cord neurolysis or epididymectomy are considered.

Lesions of the Epididymis

Mass lesions can cause noninflammatory epididymal pain, although the majority of these are painless. In a series of 1000 men undergoing ultrasound for testicular pain or swelling, 24 % were found to have epididymal cysts [65]. In a series of men undergoing ultrasound for infertility, the incidence was 7.6 % [45]. Spermatocele is another common cystic epididymal lesion that is usually asymptomatic. Solid masses of the epididymis are usually benign, with adenomatoid histology being the most common [30].

Post-vasectomy Pain Syndrome

A small subset of men develop chronic testicular pain after vasectomy that can be debilitating and difficult to treat. Post-vasectomy pain syndrome (PVPS) is defined as a scrotal pain syndrome that follows vasectomy and falls under the second type of chronic epididymitis as described by Nickel (see Table 10.3) [2]. Prospective studies have found that almost 15 % of men who had no scrotal pain before vasectomy have some scrotal discomfort 7 months postoperatively, with 0.9 % having “severe” pain affecting quality of life [66]. Overall the incidence of PVPS ranges from 1 to 52 % [67–70]. The pathogenesis of PVPS is unclear; theories include the extravasation of sperm with resultant sperm granuloma, infection, nerve entrapment, and testicular engorgement from sperm due to long-standing obstruction [67, 71]. Mechanical obstruction may be a significant contributor, as Moss et al. found closed-ended vasectomies have a threefold higher rate of PVPS than open-ended vasectomies [72]. Conservative management with NSAIDs, scrotal support, and limitations in activity is first choice. While many respond to conservative measures, often further intervention is needed. Spermatic cord blocks can provide relief of the pain, and definitive interventions may include microsurgical spermatic cord denervation, vasectomy reversal, epididymectomy, or orchiectomy [73].

Post-inguinal Herniorrhaphy Testicular Pain

Similar to the post-vasectomy pain syndrome, patients can develop post-inguinal herniorrhaphy groin pain, also known as inguinodynia . The incidence ranges from 0 to 62.9 %, with up to 10 % of patients falling into the moderate to severe pain group [74]. In a large population study of over 2400 patients who underwent either inguinal or femoral hernia repair, the incidence of groin pain significant enough to interfere with daily activity was as high as 6 % [75]. Inguinodynia differs from hernia-related groin pain, as the pain is new onset after the hernia repair and lasts longer than 3 months. The pain may be secondary to a variety of factors, including nerve trauma from retraction and dissection, neuroma formation after partial or complete transection, or nerve entrapment either by suture material or mesh associated fibrosis [74]. The pain can be classified as neuropathic or non-neuropathic , with approximately 50 % of patients falling into each category [76]. Neuropathic pain tends to be exercise induced with radiation down into the scrotum, and can be relieved by stretching or positioning techniques. Spermatic cord blocks can be diagnostic and therapeutic with up to 80 % of men with neuropathic inguinodynia reporting relief of their pain [76]. Non-neuropathic pain is secondary to a variety of etiologies, including recurrent hernias, periostitis, and spermatic cord congestion [76].

The treatment of inguinodynia begins with conservative treatment including rest and NSAIDS, similar to the treatment of post-vasectomy pain syndrome. In patients who have chronic, debilitating pain despite conservative management, surgical intervention is indicated. Surgical management is dependent on the underlying pathology of the pain. 80–95 % of patients with neuropathic pain have relief from triple neurectomy (ligation of the ilioinguinal, iliohypogastric, and genital branch of the genitofemoral nerve) [77]. Removal of mesh is effective for non-neuropathic pain secondary to spermatic cord compression from local mesh fibrosis. A microsurgical spermatic cord neurolysis can be performed concurrently if there is a significant component of associated spermatic cord/testicular pain. Intraoperative guidelines to prevent inguinodynia during routine hernia and further management are discussed in Chap. 28, “Prevention of Pain: Optimizing the Open Primary Inguinal Hernia Repair Technique .”

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree