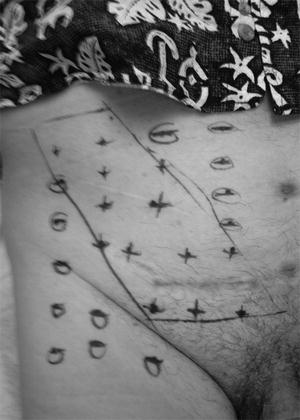

Fig. 7.1.

Cross-sectional image of an occult bilateral inguinal hernia, left more obvious than right.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the abdomen has a significan t role in the diagnostic evaluation of athletic pubalgia. It has a cost higher than both ultrasound and CT, but no ionizing radiation of CT. Its sensitivity to demonstrate soft tissue edema differences in T2-weighted images is critical to identify non-hernia causes of groin pain. As for occult hernia detection, MRI has been shown to have a sensitivity and specificity figures of 94.5 and 96.3 % [7].

Treatment

Treatment of occult hernia is fairly straightforward. This can be done as an open or laparoscopic technique. Laparoscopy is often suggested as a bridge between a diagnostic and therapeutic modality for occult hernia. This is a false logic, as a diagnostic laparoscopy will miss fat-containing hernias that give a normal contour to the pelvic floor. The peritoneum must be taken down in either a transabdominal pre-peritoneal (TAPP) or totally extraperitoneal (TEP) technique to ensure all hernia sites and pathologies are evaluated. By combining thorough patient history, physical exam, and the optimal imaging modality, the risk of missing an occult hernia can be less than 5 %.

Osteitis Pubis

Background

Osteitis pubis is an important clinical entity that deserves significant consideration in any patient who presents with groin pain without obvious hernia on exam. Several clinical features separate osteitis pubis from other groin pain diagnoses. The pain most commonly localizes within the lower abdominal wall and tends to be more medial (between the external ring and the pubic symphysis). As radiographic technology has improved, osteitis pubis is now recognized as a cluster of different injuries to the muscles, tendons, and osseous structures of the lower abdominal wall and pelvis. These include rectus tendinitis, conjoined tendonitis, pubic ramus avulsion fractures, and pubis symphysitis, adductor tendonitis, and gracilis tendonitis. The mechanism of injury in athletic pubalgia combines two physical phenomena: repetitive motion injury and muscle development asymmetry. Individuals at highest risk for the development of osteitis pubis are young athletes in sports that require high-intensity training in which quick changes in speed and direction are required. Another component of this injury mechanism is long-term training in which asymmetric muscle development is promoted. This muscle development imbalance can be either between legs and torso or between right and left sides of the body.

For example, when the foot is planted to accelerate speed or change of direction, the power in the legs must be balanced by the torso to move the entire body in the same direction. As the adductor and gracilis muscles contract, they exert pulling force on the inferior edge of the pubic ramus and pubic symphysis. The pubic symphysis acts to stabilize both halves of the pelvis to the opposing force vector. The rectus muscle then contracts to bring the torso in line with the new vector force, exerting a pulling force on the superior edge of the pubic ramus and symphysis. If the athletic training activity promotes leg muscle development over abdominal wall muscle development (typically the rectus muscle), or promotes right-sided muscle development over the left, a relative pelvic instability can develop. This allows chronic and recurring muscle, tendon, or symphyseal trauma that is collectively known as osteitis pubis. This injury mechanism helps to explain why certain sports and athletic positions have a higher incidence of osteitis pubis: the football player who stops and starts by planting the same pivot foot, the soccer player or punter who plants the left foot and creates the burst kick with the right foot, and the sprinter who explodes from the starting block using the same staggered foot position.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of osteitis pubis begins with a history and physical exam. High-intensity athletes doing year-round training in sports like soccer, football, and track have the highest incidence of injury for the reasons explained above [8]. Commonly, the patient will admit to a chronic and recurring set of symptoms for which they have self-medicated or self-limited their training to allow healing. But upon restarting competitive training, the symptoms recur, and they seek the surgeon to help get back to full speed.

The goal of the physical exam is to best localize the focal area of pain. Osteitis pubis can be divided into three zones for focal pain: suprapubic, intrapubic, and infrapubic. Suprapubic sources of pain include injuries to the rectus muscle, rectus tendon, conjoint tendon, and the periosteum of the pubic rami. Intrapubic sources of pain stem mainly from injury to the pubic symphysis and its fibrocartilaginous interpubic disk. Infrapubic sources of pain include injury to the gracilis muscle, the adductor longus muscle, the tendinous origins of these muscles, and periosteum of the pubic rami.

On examination, the pain can often be elicited by manual palpation. A pubic symphyseal injury can be assessed by performing the spring test. With the patient in supine position, the examiner places direct downward pressure with a hand on each side the pubis. Pain with a rocking motion can indicate instability and inflammation of the fibrocartilaginous interpubic disk. Rectus abdominis tendonitis can be assessed with downward pressure medially and above the pubis and may elicit pain in rectus tendon origin on the pubic crest. It can be difficult to assess for laterality, and this injury can be bilateral in nature. Manual pressure applied slightly more laterally, but medial to the external ring, may indicate conjoint tendonitis. Less severe symptoms not provoked by manual exam may be elicited by a series of exercise tests. A simple bent-knee sit-up, a sitting resistance to thigh adduction maneuver, or a cross-legged resistance to knee lift may produce the typical symptoms [9]. The pain generated by injury to the adductor longus or gracilis typically presents below the inguinal canal, but may radiate to the medial thigh and scrotum. Both the adductor longus and gracilis muscles share their origin on the anterior surface of the inferior pubic ramus. The insertion on the surface of the femur defines the adduction movement that this muscle group has. The adductor or gracilis damage most often occurs at the origin in the pubic rami. This can be muscle and tendon tearing or periosteal microfractures of the pubic bones. On physical exam, pain can typically be elicited by deep palpation of the inferior pubic ramus. A provocative maneuver on examination is a bent-knee raise or a sitting resistance to thigh adduction.

Radiographic evaluation of osteitis pubis is a valuable method to validate the clinical exam in the diagnosis of osteitis pubis. Though modalities such as plain pelvic x-ray, ultrasound, CT, and nuclear medicine study have been used to help make the diagnosis, MRI has become the main imaging modality to both diagnose and confirm resolution of the inflammatory process [10]. Figure 7.2 demonstrates a tendon tear in the adductor longus at the pubic bone. Note the increased tissue edema indicated by the smudged appearance of the tissue. In fact, because of MRI’s sensitivity for musculoskeletal edema changes, it may lack usefulness as a screening modality for asymptomatic at-risk individuals. A 2006 study of scholarship male soccer players showed that MRI scans showed moderate to severe bone marrow edema at the pubic symphysis in 11 of the 18 asymptomatic players. Substantial amounts of bone marrow edema at the pubic symphysis can occur in asymptomatic soccer players, and it is only weakly related to the development of osteitis pubis [11]. Therefore, MRI should be used to confirm the clinical suspicions provided by the history and physical exam.

Fig. 7.2.

Tendon tear in the adductor longus at the pubic bone. Note the increased tissue edema indicated by the smudged appearance of the tissue.

Treatment

Treatment of osteitis pubis is a simple prescription that is hard to follow for the patient and sometimes the trainer, coach, or parent. After the diagnosis is made, immediate cessation of strenuous and aggravating activities is mandated. The mainstay treatment is typically nonoperative, most commonly beginning with 6 weeks of rest, though low-impact and cardiac workouts can often be tolerated. Daily scheduled nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications are prescribed as tolerated. After the 6 weeks of rest, a rehabilitation program focused on cross-training types of stretching and lifting exercise can be started with a physical therapist [12]. The goal with rehabilitation is to establish muscular balance between the adductor and abdominal regions, thereby reducing the risk of early reinjury. Fricker et al. reported an average time to full recovery after conservative treatment of 9 months for men and 7 months for women [13]. If symptoms do not resolve after rest and rehabilitation programs, a corticosteroid injection treatment may be considered. A 3 mL mixture of 1 % lidocaine, 0.25 % bupivacaine, and 4 mg of dexamethasone injected into the interpubic disk of the pubic symphysis has reported good results in immediate pain relief and progression to full activities in a case series [14].

Unique to the adductor longus tendonitis is the possibility of surgical tendon release. Due to the redundancy in adductor musculature of the thigh, release of the adductor longus at its pubic bone origin is well tolerated with little loss of adduction strength and function. Gill et al. describe the surgical technique [15]. For those whose rest, rehabilitation, and corticosteroid injection fail to permit full recovery, the diagnosis of osteitis pubis must be questioned. Alternative chronic joint inflammatory conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis should be considered. Also, though rare, infectious osteoarthritis should be investigated. These diagnoses may lead to surgical debridement of the pubic bone and the damaged disk.

Nerve Entrapment

Inguinal nerve entrapment is a painful condition that is most associated with post-hernia surgery complaints. In the context of athletic pubalgia, nerve entrapment is a primary anatomic problem that should be in the differential diagnosis of athletes with groin pain that limits competitive or training activities. There are three distinct nerves in the inguinal region that have well-documented pathology and treatment strategies: ilioinguinal, genitofemoral, and obturator nerve entrapment syndromes. We will consider each separately.

Ilioinguinal Nerve

Ilioinguinal nerve entrapment was described by Kopell in the New England Journal of Medicine in 1962 [16]. The ilioinguinal nerve originates from the L1–2 nerve roots and has both motor and sensory functions. The motor innervation of the transversus abdominis and the internal oblique muscles generates muscle tone in the lower lateral abdominal wall. The sensory function gives touch and temperature sensation to the skin over the inguinal ligament, labia majora or scrotum, and the medial thigh. The pain syndrome can be caused by irritation, injury, or trauma to the nerve as it exits the retroperitoneum and pierces both the transversus abdominis and internal oblique muscles to travel within the inguinal canal. It is not a problem limited to athletes, but rather the entrapment may be an anatomic variant whose injury is worsened by intense physical training. A second mechanism is injury to the nerve and can be related to tears in the overlying external oblique aponeurosis that entrap the nerve. This injury has been coined “hockey players’ hernia.” Regional dermatome mapping can be done in the office to demonstrate if a specific nerve distribution correlates with the patient’s symptoms. Figure 7.3 is an office dermatome mapping that shows ilioinguinal nerve distribution as a possible source of pain.