82 Genitourinary Trauma

• Evaluate suspected genitourinary tract injuries in retrograde fashion; check for urethral disruption before bladder rupture and bladder rupture before ureteral or kidney injury.

• Suspect urethral injury in blunt trauma patients with a significant pelvic fracture, blood at the urethral meatus, gross hematuria, absent or abnormally positioned prostate on digital rectal examination, and ecchymosis or hematoma involving the penis, scrotum, or perineum.

• Evaluate urethral integrity by retrograde urethrography when urethral injury is suspected and a urinary catheter cannot easily be placed with a single gentle attempt.

• Suspect bladder rupture in blunt trauma patients with pelvic trauma and gross hematuria and in those sustaining a significant pelvic fracture.

• Suspect upper tract (kidney or ureter) injury in blunt trauma patients with gross hematuria or with microscopic hematuria when the patient has sustained a significant decelerating mechanism or exhibits hypotension.

• Suspect genitourinary involvement when any penetrating injury is inflicted in proximity to the genitourinary system.

Pathophysiology

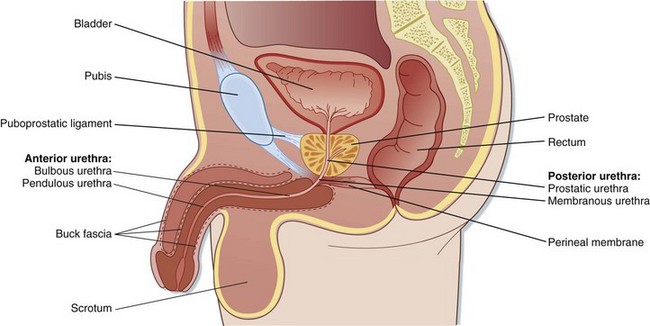

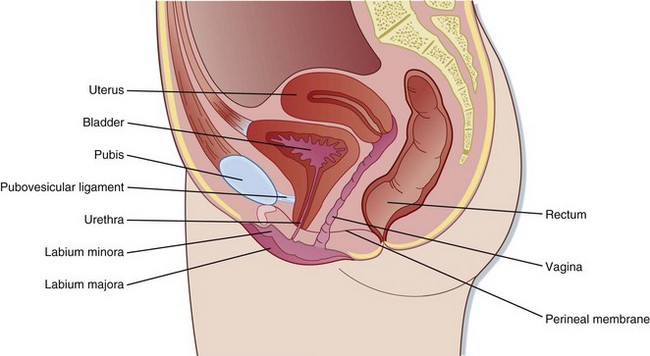

Anatomically, the genitourinary system is divided into lower and upper tracts. This division is clinically important because specific mechanisms tend to injure different parts of the genitourinary system. The lower genitourinary tract consists of the external genitalia, urethra, and bladder (Figs. 82.1 and 82.2). The upper genitourinary tract consists of the ureters and kidneys.

Urethra

The male urethra is divided into anterior (bulbous and pendulous) and posterior (prostatic and membranous) portions. Traditionally, this division has been described at the level of the urogenital diaphragm; however, recent work has questioned the existence of this structure, as classically taught.1–3 Regardless, the weakest point of the posterior urethra is the bulbomembranous junction, and it is the area where the majority of posterior urethral disruptions occur.1

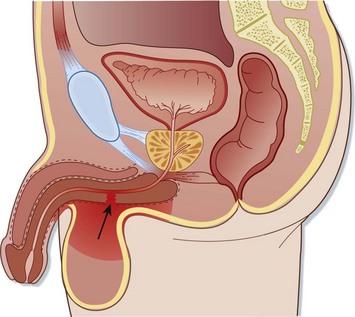

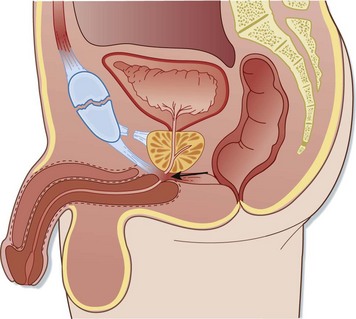

Injuries to the anterior urethra occur from direct blows, straddle injuries, or instrumentation or in conjunction with a penile fracture (Fig. 82.3). By contrast, posterior urethral injuries usually occur in the setting of significant pelvic fractures, often caused by motor vehicle collisions (Fig. 82.4). Penetrating injuries may be inflicted by gunshot wounds, knives, or other sharp objects. Urethral injuries are much less common in women because the female urethra is short and relatively mobile and lacks significant attachment to the pubis.

Fig. 82.4 Posterior urethral injury.

Note the displacement of the prostate by the hematoma at the site of injury (arrow).

Overall, urethral disruption accompanies pelvic fracture in approximately 5% of cases in women and up to 25% of cases in men.1,4 However, the risk for urethral injury varies with the type of pelvic fracture. High-risk fractures include concomitant fractures of all four pubic rami (straddle fractures; Fig. 82.5) or fractures of both ipsilateral rami accompanied by massive posterior disruption through the sacrum, sacroiliac joint, or ilium. Low-risk injuries include single ramus fractures and ipsilateral ramus fractures without disruption of the posterior ring. The risk for urethral injury approaches zero with isolated fractures of the acetabulum, ilium, and sacrum.1 Posterior urethral disruption occurs when a significant pelvic fracture causes upward displacement of the bladder and prostate. Avulsion of the puboprostatic ligament is followed by stretching of the membranous urethra and subsequent partial or complete disruption at the anatomic weak point, the bulbomembranous junction.1

Ureters

Ureteral injury is rare and occurs in less than 1% of all genitourinary injuries.5 In adults, penetrating injuries account for approximately 90% of cases, most commonly inflicted by gunshot wounds.6 In children, the most common mechanism is blunt avulsion at the ureteropelvic junction as a result of a motor vehicle collision or a fall from a height. This injury pattern is thought to be due to the increased mobility of the pediatric vertebral column, which allows extreme hyperextension that results in upward displacement of the kidney and separates it from the relatively immobile ureter.

Kidneys

Significant force is required to injure the kidney. Motor vehicle collisions, falls, direct blows, and lower rib fractures are common mechanisms. Significant decelerating force may cause avulsion of the renal pedicle. In children, bicycle accidents represent a prominent mechanism of renal injury.7 Penetrating injuries may be inflicted by gunshot wounds, knives, or other sharp objects.

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

External Genitalia Injuries

Penile fracture is often accompanied by an audible snapping sound and is followed immediately by severe pain, detumescence, swelling, and ecchymosis. The corpus spongiosum is involved in 20% to 30% of cases, and urethral injury occurs in 10% to 20%. If the Buck fascia remains intact, the swelling and ecchymosis are confined to the penile shaft. If not, blood and urine may dissect into the scrotum, perineum, and suprapubic spaces.8,9

In patients with penetrating mechanisms, a careful and complete physical examination should be conducted to search for associated or additional occult injuries. In one series, gunshot wounds involving the penis were associated with injury to other organ structures in 80% of cases.10 Violation of the corpora cavernosa requires operative intervention and is heralded by an expanding penile hematoma, significant bleeding from a wound to the penile shaft, or a palpable corporal defect.

Injuries to the female genitalia are often associated with pelvic fractures. Important mechanisms include physical or sexual assault, consensual intercourse, and penetrating injuries. In the presence of a pelvic fracture or blood at the introitus, meticulous vaginal examination is mandated. Complications of missed vaginal injuries include infection, fistula formation, and significant hemorrhage.11,12 In one series, 25% of women sustaining injury to the external genitalia required red blood cell transfusion because of blood loss from the genital injury alone.11

Ureteral Injuries

Hematuria (gross or microscopic) is not a reliable predictor of ureteral injury because the findings on urinalysis are normal approximately 25% of the time.7,13 The diagnosis is frequently missed on the initial evaluation because the signs and symptoms are minimal and nonspecific. Delayed findings include fever, flank pain, and a palpable flank mass (urinoma). Ureteral injury should be considered in patients with any penetrating injury that has a trajectory in proximity to the ureter.

Digital Rectal Examination

Classic teaching has held that digital rectal examination provides useful clinical information in the evaluation of a blunt trauma patient who has sustained a pelvic fracture or in whom a urethral injury is suspected. The technique described includes evaluation for an absent or high-riding prostate, the presence of which may be associated with posterior urethral disruption and the need for prompt investigation for urethral integrity. However, multiple studies have now demonstrated a relative lack of utility of digital rectal examination for the detection of urethral injuries.14–16 Accordingly, the decision to evaluate for urethral injury should not rely solely on the findings of digital rectal examination but instead should consider additional clinical features, including the mechanism of injury, physical examination findings such as a scrotal or perineal hematoma or blood at the urethral meatus, and the presence and type of any associated pelvic fracture.