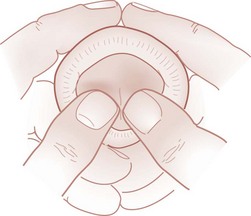

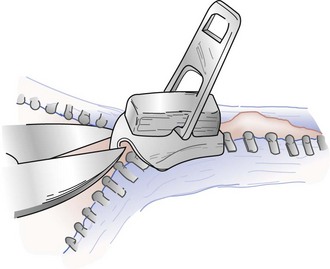

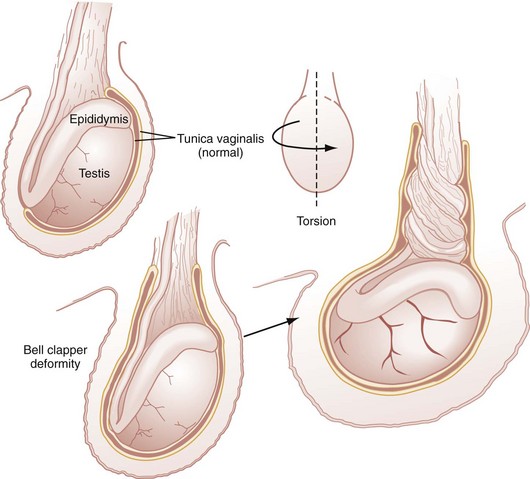

Chapter 174 Principles of Disease.: Priapism is the engorgement of the dorsal corpora cavernosa, resulting in dorsal penile erection and ventral penile flaccidity. The more common low-flow priapism is secondary to decreased venous outflow and is characterized by prolonged painful erection. Sickle cell disease and leukemia are responsible for the majority of cases in children. Immunosuppressive disorders, anticoagulation, and intracavernosal injection of agents such as papaverine, phentolamine, and prostaglandin E1 also can result in priapism. Other drugs, such as phenothiazines, sedative-hypnotics, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, antihypertensives, anticoagulants, and drugs of abuse (e.g., cocaine, alcohol, marijuana), may be causal. Priapism complications include penile fibrosis, urinary retention, and impotence. Clinical Features.: Priapism is a clinical diagnosis and can be distinguished from other causes of erection by careful history and complete physical examination. The history should include past medical history with attention to previous treatment of anemia, leukemia, sickle cell disease, or drug abuse and current history of trauma or symptoms of immunosuppressive disease. Although priapism is a clinical diagnosis, laboratory studies may assist in isolation of the cause of the condition. A complete blood count (CBC), urinalysis, and coagulation studies may be useful in some cases. Diagnostic studies of penile blood flow may be indicated in cases for which the cause is unclear. Studies that the urologist may request include magnetic resonance imaging, color Doppler cavernosography, and technetium Tc-99m penile scanning. Angiography is helpful in localization of the arterial bleeding site in high-flow priapism. Differential Considerations.: The differential diagnosis for priapism in children differs from that in adults. In adults, penile erection from sexual arousal, urethral foreign bodies, Peyronie’s disease, spinal cord injury, and penile implants may occur, but these etiologic factors are rare in children. Anticoagulation, drugs of abuse, medications, trauma (including spinal trauma), Kawasaki disease, leukemia, and sickle cell disease are associated with priapism in children. Management and Disposition.: Management centers on hydration, pain control, relief of urinary obstruction, and treatment of any other underlying conditions. Local anesthesia by a dorsal nerve block with 1% lidocaine without epinephrine may be beneficial. In patients with sickle cell disease, treatment with oxygen, hydration at 1.5 times maintenance volume, and analgesics should be initiated. Low-flow priapism may respond to sitz baths or hot compresses because the heat increases blood flow, thereby potentially relieving the obstruction. Oral terbutaline (adult dose 5-10 mg, followed by another 5-10 mg 15 minutes later) produces resolution in about one third of patients. If no resolution occurs within 30 minutes of treatment, aspiration and irrigation therapy is required. Cavernosal aspiration plus irrigation has been effective in patients with low-flow priapism. This procedure should be performed within the first few hours of symptom onset and rarely is beneficial after 48 hours. Vasoactive substances such as phentolamine and phenylephrine may be used for irrigation therapy; however, these are best administered with urologic consultation. Parenteral vasodilators, such as methylene blue, hydralazine, and terbutaline, also have been tried with variable success, and therefore the treating urologist can help ascertain the best treatment approach.1–4 Exchange transfusion for patients with priapism and sickle cell disease previously has been recommended; however, this treatment may not offer any advantage over conventional therapy and has been associated with serious neurologic sequelae, as in the so-called ASPEN syndrome (association of sickle cell disease, priapism, exchange transfusion, and neurologic events).2,3 Patients with leukemia may respond with detumescence after chemotherapy is begun. High-flow priapism can be effectively addressed by arterial embolization. Studies have shown success with the use of autologous blood clot embolization.4 If nonsurgical approaches are unsuccessful, referral to a urologist for a corpus cavernosum–glans shunt procedure may be necessary. Ultrasound-guided compression of the perineal arteriocavernous fistula has been successful.5 Interventions should be initiated within 12 hours of symptom onset to avoid long-term dysfunction and irreversible infarction.6 Patients with persistent priapism or underlying disorders, such as leukemia or sickle cell disease, may require hospitalization. Pediatric urologic consultation should be arranged as soon as possible. If the priapism has been treated successfully, the patient may be discharged home after some period of observation with urologic specialist follow-up. Principles of Disease.: Phimosis is a pathologic condition of the uncircumcised penis in which constriction of the foreskin prevents retraction of the prepuce from the glans. It can result in pain, hematuria, glans ischemia, infarction, and urinary outlet obstruction. Most cases are physiologic, representing normal development, and do not require intervention. Only 4% of newborn boys have a fully retractable foreskin. This percentage increases with age: 25% of 6-month-old, 50% of 1-year-old, 80% of 2-year-old, and 90% of 4-year-old boys have fully retractable foreskins.7 Phimosis also may result from trauma, infections, chemical irritation, poor hygiene, and congenital abnormality or be a complication of circumcision. Clinical Features.: Phimosis is a clinical diagnosis. History may reveal that the foreskin is unretractable, along with narrowing or diversion of the urinary stream and bulging out of the foreskin with urination. Pain and hematuria may be accompanying features. Management and Disposition.: Because the ability to retract the foreskin fully is age related, parents should be advised not to retract the prepuce forcefully. Gentle retraction with good hygiene should be stressed. If signs of urinary outlet obstruction are present, dilation of the prepuce or the urethral meatus or both can be performed by gentle use of forceps. With vascular compromise of the glans, a dorsal split procedure, circumcision, preputial plasty, or balloon dilation may be necessary.8,9 Topical steroid treatment (with betamethasone valerate 0.6% cream) for 6 weeks has been 87% effective in reducing inflammation and treating phimosis.10–12 In patients with severe stenosis, obstructive uropathy can result. In such rare cases, blood urea nitrogen (BUN) and serum creatinine levels should be obtained, and a renal ultrasound examination should be performed if signs of obstructive renal failure are present. Patients who are able to urinate and have no evidence of severe infection or ischemia can be discharged from the ED with outpatient urologic follow-up. Principles of Disease.: Paraphimosis is another pathologic condition of the uncircumcised penis in which the proximal foreskin cannot be returned to its anatomic position covering the glans penis, resulting in distal venous congestion with the potential for dire consequences. Paraphimosis can be caused by infection, masturbation, trauma, or hair or clothing tourniquets. Iatrogenic causes include failure to reduce the foreskin after a medical examination. Paraphimosis constitutes a true urologic emergency and can result in arterial compression, penile necrosis, and gangrene. Clinical Features.: The patient typically is anxious, and the history often reveals that the parents or the patient retracted the foreskin and then could not replace the foreskin over the glans (Fig. 174-1). The history should include verification that the patient is uncircumcised because hair tourniquet syndrome in a circumcised patient may mimic paraphimosis. Physical examination reveals a flaccid proximal penis with erythema and engorgement distal to the obstruction. The foreskin is retracted, and cellulitis may be present. The diagnosis of paraphimosis is based on clinical findings, but if a penile foreign body is a concern, radiographs can be obtained after relief of the vascular occlusion. Management and Disposition.: Pain can be controlled either parenterally or by a local dorsal penile nerve block. Procedural sedation also may be necessary. Placement of a finger of a rubber glove filled with ice water over the glans and foreskin can reduce the edema. Circumferential compression of the penis starting at the glans also can reduce the edema. Compression may need to be held for several minutes to achieve adequate reduction of edema. Manual reduction may be necessary, with application of gentle, steady pressure on the glans with both thumbs while the shaft is pulled straight (Fig. 174-2). Another method is to puncture the edematous foreskin with an 18- or 21-gauge needle.13,14 The puncture may be followed by squeezing of the glans penis to further facilitate fluid drainage. Dorsal band traction has been performed in some cases with Adson forceps applied directly to the band formed by the retracted foreskin and application of traction and countertraction to loosen the constriction. If all such attempts fail, urologic consultation proceeding to circumcision or a dorsal slit procedure may be necessary. Patients can be discharged home after reduction if they are able to void spontaneously and urologic follow-up care can be arranged. Any evidence of cellulitis or necrosis warrants hospital admission, intravenous antibiotics, and urologic consultation. Principles of Disease.: Balanoposthitis, an inflammation that involves the glans and the foreskin, occurs in up to 6% of uncircumcised males.15 Balanitis involves the glans penis only. The primary cause of balanoposthitis is infection; however, chemical irritation, trauma, fixed drug rash, and contact dermatitis also can be contributory. Infectious organisms are gram negative and gram positive, including group A beta-hemolytic streptococci and rarely Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia.16 Recurrent episodes of Candida albicans balanoposthitis should raise suspicion for diabetes mellitus. Clinical Features.: Physical examination reveals penile erythema, edema, and possibly a discharge (Fig. 174-3). Systemic symptoms and signs such as fever, vomiting, and diarrhea are unusual. Diagnosis is clinical and treatment is based on clinical findings; however, if symptoms are severe, the offending organism can be identified by culture of any discharge. Management and Disposition.: Management includes emphasis on adequate hygiene with sitz baths to reduce inflammation. Painful micturition can be addressed by having the child urinate while in a bath of warm water. In patients with cellulitis, antibiotic treatment with agents effective against Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus pyogenes is recommended. Seven days of a first-generation cephalosporin is an appropriate regimen. If group A beta-hemolytic streptococci are identified, a streptococcus-specific antibiotic is required.17 Severe inflammation may be treated with 0.5% hydrocortisone cream applied sparingly to the area. Candidal infections should be treated topically with antifungals. A blood glucose determination should be considered in patients presenting with recurrent candidal balanoposthitis. Patients with a toxic appearance or those who exhibit evidence of cellulitis or constricting phimosis with uropathy should be hospitalized for appropriate management. Circumcision may be required for patients with recurrent disease. Principles of Disease.: Although there remains societal controversy about circumcision, it is usually advocated for prevention of phimosis, paraphimosis, recurrent balanoposthitis, urinary tract infections, and penile cancer. Any of three techniques can be used: application of a Plastibell or Gomco clamp, excision, or dorsal slit procedure. The choice of procedure depends on the preference of the operator. The most common complication of these procedures is hemorrhage, which usually is minor and can be controlled by direct pressure, silver nitrate application, or suture placement. Significant bleeding may be a sign of a blood dyscrasia. Localized, systemic, or urinary tract infection also can occur. Management and Disposition.: Postoperative pain usually resolves within 12 to 24 hours. Occlusive dressings can contribute to urinary retention and edema and should be removed. Stenosis of the now exposed urethral meatus may result from prolonged exposure to the ammonia in urine. Application of a Plastibell that is too small also can lead to meatal stenosis in 8 to 31% of cases.18 Signs and symptoms include pain with urination, bloody discharge resulting from an inflamed meatus, high-velocity stream, and the need to sit while voiding. Postcircumcision phimosis may result if excess foreskin remains. If the constriction is severe and urinary outlet obstruction occurs, dilation of the stenosis can be performed with a hemostat. Surgical revision usually is necessary.19 Zipper entrapment of the foreskin also can occur in children, typically those between 2 and 6 years of age. The zipper can be removed with bone or metal cutters or a mini-hacksaw to cut the median bar of the zipper20,21 (Fig. 174-4). The zipper falls apart, and the foreskin is freed. Although local anesthesia is not necessary, the patient may be anxious and require sedation before its removal. Success has been reported with soaking of the penis in mineral oil before zipper removal.22 Additional methods to release the foreskin under the zipper mechanism include cutting of the zipper below the entrapment and pulling the two halves of the zipper apart; cutting of the zipper teeth above and below the entrapment and, with pliers, squeezing the median bar to allow more room to disengage the trapped prepuce; and insertion of a flat screwdriver between the faceplates of the zipper mechanism to pry open the faceplates and allow the prepuce to be released.23–25 Parents should be instructed to encourage their children to wear underwear to decrease the risk of entrapment. Principles of Disease.: Epididymitis is inflammation of the epididymis, which is located along the posterior aspect of the testicle. The most common cause is infectious, and the etiology varies by age. Adolescents should be evaluated for possible sexually transmitted diseases, such as N. gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia trachomatis. Patients may have a history of previous urinary tract infections, anatomic abnormalities, or previous genitourinary instrumentation. Urinary tract infections leading to epididymitis typically are caused by viruses or bacterial agents, such as Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Proteus, or Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Clinical Features.: Patients present with a painful, edematous scrotum and tenderness at the epididymis (Fig. 174-5). A urethral discharge may be present, particularly when the condition is secondary to a sexually transmitted disease. Systemic signs and symptoms, such as nausea, vomiting, fever, and lower abdominal, scrotal, or testicular pain, also may be present. Infants and young children may present with fever without other symptoms. Accordingly, in the ED evaluation of all children with fever or other systemic symptoms or signs, a complete examination should include a genitourinary examination. Figure 174-5 Epididymitis in a 5-year-old boy; note mild swelling and erythema on the left. (Courtesy Marianne Gausche-Hill, MD.) Diagnostic Strategies.: Urinalysis and urine culture should be part of the ED evaluation for all infants and children younger than 2 years. In children 2 years of age or older, urine culture may be performed only if the urinalysis results indicate urinary tract infection. Lack of pyuria does not rule out epididymitis because up to 50% of patients may have normal results on such studies. CBC may show leukocytosis, although this finding is nonspecific. Any urethral discharge should be cultured and sent for Gram’s stain and tests for N. gonorrhoeae and C. trachomatis. Color Doppler ultrasonography is not necessarily performed in all children with suspected epididymitis. However, if there is doubt about the diagnosis, it is the preferred diagnostic study because it does not require placement of an intravenous line and is more readily available at all hours of the day. If color flow Doppler ultrasonography or radionuclide scintigraphy is performed, it will reveal a normal testis and preserved or increased vascular flow toward the side of the inflamed epididymis.26,27 Management and Disposition.: Scrotal elevation, placement of ice packs on the swollen area as tolerated, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory or narcotic medications are useful to control pain and inflammation. If urethral discharge is present, the adolescent patient should be treated presumptively for both N. gonorrhoeae and C. trachomatis. The treatment for sexually acquired epididymitis in children 9 years of age or older consists of ceftriaxone 250 mg intramuscularly, followed by doxycycline 100 mg orally twice a day or tetracycline 500 mg orally four times a day. A single 1-g dose of azithromycin may also be used to increase compliance. Patients younger than 9 years should be treated with erythromycin 50 mg/kg orally per day, divided four times a day. The course of treatment typically ranges from 7 to 14 days, depending on the antibiotic regimen. In children, non–sexually acquired epididymitis without evidence of urinary tract infection may be managed expectantly with analgesics for pain.28 Infants with or without positive findings on urinalysis and young children with positive urinalysis findings may be treated with trimethoprim twice a day or cephalexin three times a day if a bacterial urinary tract infection is suspected. Other antibiotic options include oral erythromycin, clarithromycin, and azithromycin for patients who do not respond to other therapies because Mycoplasma genitalium and Ureaplasma urealyticum may cause a more chronic form of epididymitis. Infants and children with epididymitis may be discharged for follow-up by their primary care physician, and urine cultures should be checked to determine definitively if urinary tract infection is present. Patients with systemic symptoms and toxicity should be admitted for intravenous antibiotic therapy with either ceftriaxone or cefotaxime. Children need close urologic follow-up to rule out any contributing anatomic abnormalities and to ensure that the antibiotic chosen treats the infecting organism. Principles of Disease.: Torsion of the spermatic cord is a common cause of an acutely painful scrotum. Delay in diagnosis and treatment can result in loss of spermatogenesis and, in severe cases, necrotic, gangrenous testes. Testicular salvage rates are time dependent; the success rate is 96% if detorsion is performed less than 4 hours from symptom onset, decreasing to less than 10% if there is more than a 24-hour delay to treatment.29 The overall incidence of testicular torsion is 1 in 4000, with a peak incidence at age 13 years. Testicular torsion has been reported in all age groups, from the developing fetus to the elderly, but is most common in adolescence. The testis enters the scrotum through the inguinal canal after descent from the abdomen. The peritoneum invaginates through the canal and partially covers the testis and epididymis, forming the tunica vaginalis. Typically, the tunica vaginalis attaches to the posterior wall of the hemiscrotum and superior pole of the testis to achieve testicular fixation. If the tunica completely covers the testis and attaches higher up on the spermatic cord (bell clapper deformity), proper testicular fixation does not occur, and there is a predisposition to torsion (Fig. 174-6). In intravaginal torsion, the testicle may rotate within the tunica vaginalis, thereby constricting the arterial blood flow. Extravaginal torsion is seen most commonly in neonates who are premature and also can occur antenatally. Clinical Features.: Patients present with acute scrotal pain and swelling, an elevated testicle, and, typically, absence of the cremasteric reflex.30 This reflex can be demonstrated by lightly stroking the skin of the inner thigh downward from the hip toward the knee. This causes the cremaster muscle on the ipsilateral side to contract rapidly and results in elevation of the testicle. Although in one series the cremasteric reflex was absent in 100% of patients with torsion and in only 14% of patients with epididymitis, the presence of the cremasteric reflex does not preclude testicular torsion. Abnormal epididymal and testicular position also may be noted, with left-sided torsions slightly more common than right. Nausea, vomiting, and a low-grade fever also may be seen. In the patient with an undescended testicle who presents with abdominal pain, torsion should be a consideration.31 Diagnostic Strategies.: Unless an alternative diagnosis is absolutely secure (e.g., epididymitis), the patient should be evaluated for testicular torsion. Alternatively, with a relatively confident clinical diagnosis of torsion, diagnostic testing should not delay appropriate management. Results of a urinalysis are rarely helpful as pyuria can be seen in cases of testicular torsion and epididymitis. The widely preferred diagnostic study for the prospect of torsion is color flow Doppler ultrasonography. This technique has a sensitivity of 79 to 86%, with a specificity of almost 100%, for detection of testicular torsion. Scintigraphy has a sensitivity ranging from 79 to 100% and a specificity of 89 to 100%.27,32,33 Magnetic resonance imaging has been evaluated as another diagnostic modality, with a sensitivity in one study of 93% and specificity of 100%.34 In cases of indeterminate ultrasound findings, the urology consultant should be notified for disposition decisions; in addition, scintigraphy may be performed as resources allow. When clinical suspicion is strong, surgical exploration should not be delayed for diagnostic studies, especially in patients in whom duration of symptoms is less than 12 hours. Management.: If the patient presents within 12 hours of symptom onset, immediate surgical exploration is indicated, predicated on clinical findings or confirmatory clinical studies.35 Detorsion of the affected testicle is performed, followed by an elective orchiopexy of the contralateral side to avoid recurrence. Approximately 40% of patients have a bell clapper deformity of the contralateral testicle. Manual detorsion also may be performed by rotation of the testicle in an “open book” fashion as viewed from below, from medial to lateral, until detorsion is complete.36 Because the procedure is painful, sedation and pain relief should be considered before this intervention. Manual detorsion should be attempted only if there is a delay in getting a urologist to come in for operative detorsion and the patient has had continuous pain for less than 24 hours or if, in the judgment of the emergency physician, the time zone of opportunity to salvage the testis has not passed. A varicocele is a collection of venous varicosities of the spermatic veins in the scrotum caused by incomplete drainage of the pampiniform plexus. Incidence rates of 14 to 16% in adolescent males have been reported,37 but varicoceles are rare in children younger than 10 years.38 Left-sided varicoceles account for 85 to 95% of cases; however, bilateral varicoceles may be present in up to 22% of patients.39 Intra-abdominal disease should be suspected in cases of right-sided varicocele because these usually are caused by inferior vena cava thrombosis or compression of this vessel by tumors.40 The acute presentation of a left-sided varicocele should raise suspicion for renal cell carcinoma with obstruction of the left renal vein. The dilated venous collection may be tender on physical examination. It can be palpated superior and posterior to the testis and usually is more pronounced with the patient in the upright position. Therefore, the patient should be examined in both the standing and supine positions. Patients in whom scrotal swelling persists in the supine position should be evaluated with a computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen, with oral and intravenous contrast administration for conditions obstructing the renal vein. Varicoceles have been described as a “bag of worms” both in appearance and on palpation. Surgical correction may be required if the patient becomes symptomatic or has bilateral varicoceles.41 Principles of Disease.: Inguinal (direct and indirect) hernias are more common in males, with bimodal peaks before 1 year of age and then again after the age of 40 years. An indirect inguinal hernia occurs when the processus vaginalis is not obliterated in infancy and abdominal contents invaginate through this patent sac. Entrapment of mesentery, bowel, intraperitoneal organs, and the hernial sac can occur and is more common with small hernias. If the contents of the hernia can be returned to their anatomic position, the hernia is reducible; if the contents remain entrapped, it is incarcerated or irreducible. Hernias that remain incarcerated can undergo strangulation, with resultant necrosis of bowel or mesentery. Clinical Features.: Patients with incarcerated hernias may present with pain, edema extending to the scrotum, nausea, vomiting, and low-grade fever. Physical examination may reveal bowel sounds in the scrotal sac. If the inguinal mass can be palpated separately from the testes, it is possible to diagnose an inguinal hernia on clinical grounds alone. Rarely, the incarcerated and strangulated hernia can be manifested as a tense blue mass in the scrotum. Management and Disposition.: The patient should be placed in the Trendelenburg position with an ice pack applied to the groin to reduce swelling; sedation may be necessary before reduction. Slow, gentle pressure should be applied to reduce the hernia. If the pressure technique is not successful in reducing the hernia, the opposite technique can be tried: the hernia mass can be “pulled” to straighten out the entrapped contents, thereby allowing them to slip back into the abdomen. If the hernia cannot be reduced or strangulation is suspected (as indicated by fever, overlying cellulitis, or signs of peritonitis), the patient should receive fluid resuscitation, broad-spectrum parenteral antibiotics, and an emergent surgical consultation.42 Principles of Disease.: Testicular and scrotal cancer represents approximately 1% of solid tumors in children. An increased incidence of testicular cancer, in both the undescended testicle and the contralateral descended testicle, has been noted in patients with cryptorchidism. Tumor types include teratomas, embryonal carcinomas, yolk sac tumors, choriocarcinomas, Leydig cell tumors, and Sertoli cell tumors. Lymphoma and leukemia can metastasize to the testicle as well. Diagnostic Strategies.: Diagnostic evaluation includes a CBC, urinalysis, urine human chorionic gonadotropin (produced by germ cell tumors) assay, and ultrasonography of the testis. The risk for development of urinary tract infections before the age of 12 years is approximately 3% for girls and 1% for boys. Neonatal boys are more susceptible than girls to urinary tract infections, but beyond that period, infections in females prevail. Girls younger than 2 years and uncircumcised boys younger than 6 to 12 months also are especially at risk.43 Approximately 5% of children younger than 2 years with a temperature above 39° C and presenting without a source for the fever have an occult urinary tract infection.44 Urinary tract infections are also significant in the very young infant, with up to 9% prevalence in one study of febrile infants younger than 60 days.45,46 Fever duration also appears to correlate with the prevalence of urinary tract infections. Two days of fever was more likely than one day to be associated with a urinary tract infection.44 Other risk factors for female infants include white race, age younger than 12 months, temperature above 39° C, and no other identifiable source for the fever.44 Risk factors for male infants include nonblack race, similar temperature, and no other identifiable source for the fever.44 Moreover, up to 4% with a significant fever and an associated upper respiratory tract infection or acute otitis media also may have a urinary tract infection.47 By comparison, the background prevalence of asymptomatic bacteriuria is estimated to be 1 to 2% in all children.48 On the basis of renal nuclear scans, it is estimated that 75% of children younger than 5 years with a febrile urinary tract infection have pyelonephritis.45 Vesicoureteral reflux from the bladder into the ureter is a common cause of the pyelonephritis and renal scarring. Urinary tract infection in infants younger than 3 months is associated with bacteremia in up to 50% of cases; in children older than 3 months, the risk drops to 5%. Renal scarring can occur in 27 to 64% of children after pyelonephritis and may lead to renal failure and a risk for hypertension later in life.45 E. coli is the predominant cause of urinary tract infections in children; Klebsiella species are more likely to be the etiologic agents in newborn children. Enterobacter, Proteus, Morganella, Serratia, and Salmonella species also are important pathogens.49 Organisms such as Lactobacillus, coagulase-negative staphylococcus, and Corynebacterium are not considered clinically relevant pathogens in otherwise healthy children.44 In neonates and young infants, bacteremia is considered the route of infection to the urinary tract. In older children, infection in the lower tract often is the source of upper tract infection. A common cause of urinary tract infections in toilet-trained girls is believed to be improper wiping after urination. Young girls should be taught to wipe from anterior to posterior (front to back) after urination. Infants and Children Younger than 2 Years.: Signs and symptoms usually are nonspecific and include decreased oral intake, lethargy, jaundice, fever, vomiting, abdominal pain, and irritability. Young children may not be able to verbalize when urination is painful. It is assumed that a urinary tract infection in this age group represents upper tract disease and would therefore arise with more systemic symptoms and signs. Children Older than 2 Years.: Urinary tract infection in children older than 2 years can be either an isolated cystitis or upper tract disease with symptoms and signs of a more systemic nature. Cystitis usually is associated with local symptoms (i.e., suprapubic tenderness and dysuria). Clinical manifestations of pyelonephritis may include fever, costovertebral angle tenderness to palpation, abdominal pain, vomiting, and ill appearance. New-onset bedwetting also may be a sign of a urinary tract infection. Various techniques can be used for collection of urine samples from children. Because of the difficulty in cleaning the perineal area, the bag collection method is associated with an increased risk of contamination by periurethral flora; false-positive results range from 12 to 83%.45 Because urethral catheterization is almost always successful, suprapubic aspiration to obtain a urine sample is rarely needed.48,49 A suprapubic bladder aspiration may be used for young infants because the expanded bladder is located more intra-abdominally. Bladder aspiration is considered more invasive and is more painful than the urethral catheterization method.44 Chances of a full bladder and successful aspiration improve if 45 to 60 minutes have elapsed since the last diaper change. Ultrasonographic guidance has been advocated to enhance the probability of obtaining urine by the suprapubic and catheterization methods. Nursing staff can be trained to use this enhanced method of urinary collection.50,51 In children younger than 2 years, a urinalysis alone is not considered adequate to rule out urinary tract infections. As many as 10 to 50% of patients with urinary tract infection can have false-negative results on urinalysis.52,53 Nitrite and leukocyte esterase urinalysis markers have the highest combined sensitivity and specificity for detection of infection. If both markers are positive, the false-positive rate is less than 4%. The urine dipstick alone appears to work less well in young infants.45,55 Gram’s stain of the urine has a sensitivity of 93%.45,55 New guidelines have redefined urinary tract infections in children. To establish the diagnosis of urinary tract infection in children, the clinician should require both of the following: (1) urinalysis results suggesting infection (pyuria, bacteriuria, or both) and (2) the presence of at least 50,000 colony-forming units (CFU) per milliliter of a uropathogen cultured from a urine specimen.44 Old guidelines of 100,000 CFU/mL were based on studies of adult women and are considered no longer applicable to children. Renal function tests are rarely abnormal but should be performed in children with hypertension, proteinuria, or signs of dehydration. In general, blood cultures are not indicated in a majority of well-appearing children with urinary tract infection. The true-positive rate for blood culture in the presence of a urinary tract infection in older infants and young children is low, and the organism identified is invariably the same as the organism in the urine culture.56 Several other causes of dysuria in children are recognized (Box 174-1). Irritants such as bubble bath and soaps may cause local irritation and dysuria. A retained foreign body in the vagina or penis (such as toilet paper) can cause irritation or bacterial growth with associated dysuria and vaginal discharge. Pinworms in the genitourinary area can cause itching and scratching. Balanitis in uncircumcised boys also can cause dysuria and pyuria.

Genitourinary and Renal Tract Disorders

Specific Disorders

Priapism

Phimosis

Paraphimosis

Balanoposthitis

Complications of Circumcision

Penile Entrapment and Tourniquet Injuries

Scrotal Masses and Swelling

Testicular Torsion

Varicocele

Inguinal Hernia

Carcinoma

Urinary Tract Infections

Principles of Disease

Clinical Features

Diagnostic Strategies

Differential Considerations