Vasovagal Syncope

Vasovagal syncope and orthostatic collapse are associated mainly with a drop in blood pressure, tinnitus, pallor, nausea, and in some cases, short-term clouding of consciousness or loss of consciousness. The symptoms are mostly harmless and quickly reversible. Anxiety and sometimes state of sobriety also often play a role.

Treatment

Treatment

Placing the patient in a horizontal position and general measures, such as calming the patient, generally improve symptoms. Vasovagal reactions often occur during the first session in a series of local anesthetic treatments (Hanefeld et al. 2005). It is nevertheless necessary to consider more serious causes (see below) as a differential diagnosis.

Intravascular Administration of Local Anesthetics and Glucocorticoids

Generally speaking, free local anesthetic that is not bound to proteins interacts with all electrically excitable membranes following its spread into the plasma, blocking the highly specific sodium channels of the membrane. Depending on the concentration of the local anesthetic, all excitable cell systems may be affected.

Other than the local tissue toxicity (nerves, muscle) of some agents, or methemoglobinemia following prilocaine administration, the main side effects of local anesthetics affect the central venous and cardiovascular systems (Table 10.1). When the substance-specific limit value of the local anesthetic is exceeded following accidental intravenous injection and overdose, or unexpectedly rapid resorption, symptoms arise that are associated with an increase in plasma concentration of the free substance.

| Systemic toxicity | Effects on CNS Cardiovascular |

| Local tissue toxicity | Neurotoxicity Myotoxicity |

| Hematological toxicity | Methemoglobin production (prilocaine) |

| Anaphylactoid reaction | Monoester type LA >>> Amino amide type |

The development of clinical symptoms is highly dependent on the speed of uptake, the plasma concentration, and the type of local anesthetic chosen. Injections administered into the arteries leading to the brain (vertebral artery, carotid artery) result in sudden and sometimes extremely high concentrations in the CNS, with immediate symptoms. The injection of local anesthetics into peripheral arteries or veins results in a comparatively slower uptake.

Central Nervous System

The initial symptoms are those of CNS hyperexcitability; the symptoms of CNS depression develop later (Table 10.2). The symptomsmay increase gradually, or may attain a high level immediately.

Hypoventilation results in respiratory acidosis (CO2 retention) and sometimes hypoxia-related metabolic acidosis. In this case, the local anesthetic is released from the plasma protein and the amount of free, active local anesthetic in the plasma increases. More anesthetic can be found in the CNS as a result of the increased hypercapnic brain circulation, and it accumulates in the brain because ions are trapped in their active form in acidotic cells. This in turn accelerates the vicious cycle of symptoms. The risk is generally greatest with highly potent and long-acting local anesthetics such as bupivacaine and ropivacaine.

| Stage | Symptoms | Neurophysiology |

|---|---|---|

| 1 Prodomal stage | Perioral numbness, tingles, taste disorder (tinfoil) Hyperacusis Anxiety, panic | Only partially direct effects on CNS |

| 2 Preconvulsion stage | Tremor, coordination disorders Tinnitus, reduction in visual acuity Nystagmus Somnolence | Blocks inhibitory neurons in the cortex |

| 3 Convulsion stage | Generalized tonic-clonic cramping with apnea and loss of vigilance | Cramping potential: 1. Amygdaloid body 2. Hippocampus |

| 4 CNS depression stage | Coma Apnea Vasomotor failure Bradycardia Hypotension | Blocking of excitatory neurons and centers EEG neutral line (Indirect circulatory involvement) |

Treatment

Treatment

Cardiac Circulatory System

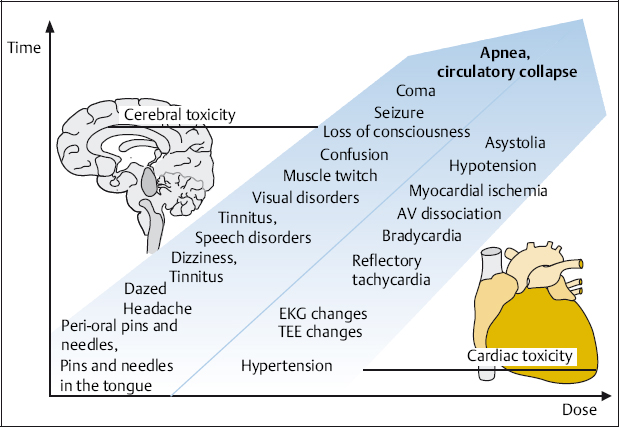

The cardiac circulatory system generally seems more resistant to the systemic action of local anesthetics. CNS symptoms typically arise at lower plasma levels than cardiac circulatory symptoms. However, this does not apply to all local anesthetics. There is significantly less difference when using long-acting agents, such as bupivacaine, compared with the mid-acting local anesthetics (lidocaine, mepivacaine, prilocaine). Indirect cardiac circulatory effects via the CNS (bradycardia, arrhythmia, and sympathicolysis) must be differentiated from the direct effects (negatively dromotropic, inotropic, and repressive of the pacemaker function in the sinoatrial nodes). Modern local anesthetics, such as ropivacaine or S-bupivacaine, seem to be better in this respect. Figure 10.1 shows the symptoms depending on the time and dosage.

Fig. 10.1 Systemic and toxic symptoms following the administration of local anesthetics.

Treatment

Treatment

Treatment is limited to symptomatic measures such as the administration of oxygen and, if necessary, artificial respiration, the administration of fluids, and vasopressors if required. If necessary, resuscitation is carried out according to the Advanced Cardiac Life Support (ACLS) standards.

Intrathecal Administration of Local Anesthetics and Glucocorticoids

When local anesthetics are accidentally injected into the subdural or subarachnoid space, the local anesthetic can reach the intracranial region and bind to the central neuronal structures, to an extent depending on the volume and dose. The typical symptoms arising from this are known as “total spinal anesthesia” (classically arising from an overdose of intrathecal local anesthetic during spinal anesthesia or from unnoticed intrathecal injection of local anesthetic during peridural anesthesia; Table 10.3).

The risk is higher during anesthetic interventions near the spinal cord, and typically during paravertebral, intercostal, stellate, celiac, and thoracic and abdominal sympathetic ganglia blocks. Total spinal anesthesia has even been described following ophthalmological and ENT blocks.

Treatment

Treatment

Treatment is symptom-related. Emergency equipment must be kept available throughout the procedure (Table 10.4).

When resuscitation according to the ACLS guidelines is carried out immediately, and when complications such as aspiration, hypoventilation, and/or hypoxia are prevented, the prognosis that the central block will recede is good (depending on the dose and type of local anesthetic administered).

NOTE

The intrathecal application of glucocorticoids is not known to have any acute life-threatening side effects.

| Coma |

| Dilated, unreactive pupils |

| Central apnea |

| Arterial hypotension (vasomotor failure) up to cardiovascular arrest |

| Stop further administration of local anesthetic |

| Free airways, administer oxygen, artificial respiration, intubate |

| Support cardiovascular system |

| Intravenous access |

| Rapid, bold administration of fluids (e. g., balanced electrolyte solutions) + hydroxyethyl starch (e. g., 6% HES 130/0.4) |

| Catecholamine administration (e. g., norepinephrine or epinephrine 0.5–1mg IV) |

Anaphylactoid Reaction—Anaphylactic Shock

Anaphylactoid reactions are immunological or paraimmunological reactions associated with the release of typical mediators—serotonin, slow-reacting substance of anaphylaxis (SRS-A), bradykinin, arachidonic acid metabolites, platelet activating factor, and histamine. These reactions should be considered as potentially life-threatening, and require rapid and adequate treatment.

The clinical reaction is to be expected within 30min of exposure to allergens; sometimes it may occur immediately. The severity of the reaction is inversely proportional to the latency time. Severe reactions can lead to cardiovascular arrest without any prior warning.

Anaphylactoid reactions are clinically divided into five levels of severity (Table 10.5). These levels are not based on the pathological mechanism of the original reaction. The symptoms range from trivial skin efflorescence, mild to severe respiratory and cardiovascular symptoms, or smooth muscle spasms (in the hollow viscera), to immediate and sudden respiratory and cardiac arrest. Symptoms can potentially begin at any level of severity and then subside, persist, or increase.

| Level | Stage | Symptoms | Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Local (at point of contact with the antigen) | Cutaneous reaction, locally restricted | Stop antigens; if necessary, with H1/H2 blocker |

| I | Mild general reaction | Disseminated cutaneous reaction (flush, urticaria, pruritis), mucosal reaction (nose, conjunctivitis), general reactions (agitation, headache, mild fever reaction) | Additional prophylactic H1/H2 blocker with widebore venous access |

| II | Distinct general reaction | Measurable, but not life-threatening cardiovascular dysregulation (tachycardia, hypotension), respiratory disorders (mild dyspnea, bronchospasm), gastrointestinal disorders (nausea, urge to urinate and pass stool) | Additional oxygen 6 1/min Glucocorticoid (prednisolone 250 mg) Balanced electrolyte solution, if need be (HES 0.5–2l) Epinephrine in some cases (0.05–0.2mg; diluted) Call emergency team |

| III | Life-threatening general reaction | Shock (severe hypotension, pallor), life-threatening smooth muscle spasms (bronchi, uterus, intestines, bladder, etc.), clouding or loss of consciousness | Additional epinephrine (0.1–0.5mg) Energetic administration of fluids (HES, small-volume resuscitation if needed) Intubation, cricothyrotomy if needed Call emergency team |

| IV | Vital organ failure | Cardiovascular arrest and/or respiratory arrest | Cardiopulmonary resuscitation following the ACLS guidelines, epinephrine (3 mg in 10 mL saline endobrachial or 0.5–1mg in a fast-running infusion) |

Treatment

Treatment

The initial treatment (see Table 10.5) consists of stopping the influx of allergens immediately. Obviously, this is not possible after the injection of a local anesthetic.

Even when symptoms are mild, IV access should be obtained right away and kept open by using a large-bore needle for the infusion of a balanced electrolyte solution. Oxygen should be administered prophylactically (this is obligatory for more severe reactions). It is advisable to administer histamine-receptor blocking agents, e. g., dimethpyrindene (Fenistil) 4mg and cimetidine (Tagamet) 200 mg, via the IV line. However, their action is not likely to be visible within the first 30 minutes. The same applies to glucocorticoids (e. g., Solu-Decortin H 250 mg).

If there is a significant drop in blood pressure, the energetic administration of fluids is indicated, e. g., a pressure infusion of hydroxyethyl starch (HES 130/0.4, 6%, 500–2000 mL). When there is a marked drop in respiration rate, the infusion of hyperosmolar colloid (e. g., Hyper-HAES at a maximum dose of 4 mL/kg body weight) may be considered.

The IV administration of epinephrine (0.05-0.2 mg; ampules up to 1 mg, diluted 1:10) is indicated in all reactions from level 2 upwards. This has an immediate vasopressor (α−effect), brocholytic (β-effect), and specific antiallergic effect. The patient must be immediately intubated and, if necessary, resuscitated according to the ACLS standards when respiratory failure (level 3) or respiratory and cardiac arrest occur.

In some cases, swelling of the pharyngeal–laryngeal mucosa may be so great that a cricothyrotomy is required to obtain an artificial airway. Laryngeal obstruction is the most common cause of death in cases of anaphylaxis. It is therefore important to pay attention right away to the symptom of “lump in the throat” (Tryba et al. 1994, Madler et al. 1998, Hofmann et al. 2001).

As far as emergency tactics go, if a resuscitation team is available, it is preferable to alarm them at an early stage. From level 1 reactions onward, the patient should be referred to a hospital emergency department. A high degree of caution is recommended, because of the unpredictability and possibly rapid development of presenting symptoms. Regrettably, there is no consensus between specialties with regard to the prophylactic provisions of expert personnel, equipment, and safety levels.

NOTE

Anaphylactoid reactions may in principle always arise following the administration of local anesthetics.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree