46 Gastrointestinal Devices, Procedures, and Imaging

• Nonfunctional feeding tubes can be safely replaced in the emergency department with a commercial tube or by making a few simple alterations to a standard Foley catheter to prolong its longevity.

• Gastroesophageal balloon tamponade tubes are used only for life-threatening variceal bleeding that is refractory to standard, first-line endoscopic and pharmacologic treatment. There is no absolute contraindication to the use of such tubes as a heroic, lifesaving measure.

Nasogastric Tubes

The Salem Sump tube is the most commonly used nasogastric tube (NGT) in the emergency department (ED). The Salem Sump is a double-lumen tube with multiple distal suction eyes. The second lumen allows venting during suction, which prevents invagination and subsequent gastric injury. Indications for its use include gastric evacuation or decompression, diagnostic aspiration of gastric contents, and infusion of therapeutic agents. Intermittent suction may be set at a pressure of less than 120 mm Hg.1 A Levin tube is a single-lumen tube with multiple distal openings for suction, referred to as “eyes.” The Levin tube’s relatively large internal diameter makes it ideal for rapid decompression or drug infusion. Intermittent suction may be set at a level lower than 40 mm Hg. A Levin tube has the same uses as the Salem tube except that it may not be used for long-term gastric evacuation.1

Indications and Contraindications

Box 46.1 lists the indications for and contraindications to the use of NGTs in the ED.

Box 46.1 Indications for and Contraindications to the Use of Nasogastric Tubes

Indications

In gastrointestinal bleeding, to monitor blood loss, which may help differentiate upper from lower tract sources of bleeding

In intubated patients, to decrease risk for pulmonary aspiration, treat gastric distention, and deliver medications

Decompression of intestinal obstruction

Treatment of paralytic ileus, intractable vomiting

Treatment of gastric outlet obstruction and distention

In trauma patients, to evaluate for transdiaphragmatic hernia when the nasogastric tube is seen above the diaphragm on a chest radiograph

Rightward deviation of the tube may be seen on a chest radiograph in patients with aortic dissection

Insertion Procedure

Tips and Tricks

Inserting a Nasogastric Tube

Warming the tube will make it more pliable and easier to advance along the curvature from the nasopharynx into the oropharynx.

Flexing the patient’s neck can help direct the tube from the oropharynx into the esophagus.

If choking, gagging, or muffling of the voice occurs, withdraw the tube to the oropharynx only. Do not remove the tube completely, or it must be repassed through the nasopharynx into the oropharynx, which is usually the most difficult and painful part of the procedure.

The tube can coil within the patient’s mouth; if problems occur when placing or verifying placement of the tube, always check the mouth.

In an unconscious patient, elevating the jaw will move the trachea anteriorly, a maneuver that can relieve pressure on the esophagus and make it easier to pass the tube.2

A lubricated, soft nasopharyngeal airway may be inserted if neither naris appears to be amenable to placement of the larger, more rigid nasogastric tube (NGT). The nasopharyngeal airway may be used to dilate the nasal passage for a few minutes and then removed to allow another attempt at placing the NGT. Alternatively, a smaller NGT may be passed through the nasopharyngeal airway into the esophagus.

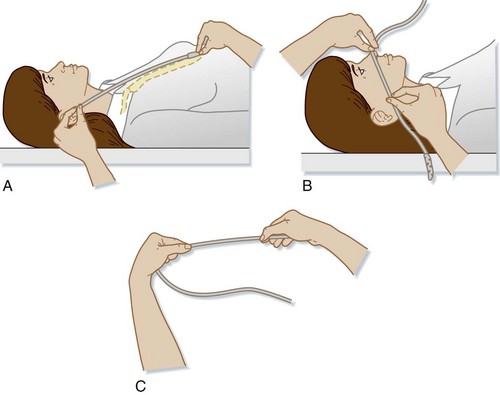

1 Estimation of Tube Length

To place the drainage eyes in the proper location in the stomach (Fig. 46.1), the length of tube to be inserted can be estimated by adding the following three measurements together3:

a: Measurement from the patient’s xiphoid process to the earlobe

b: Measurement from the earlobe to the tip of the nose

2 Nares Patency Check, Anesthesia, and Vasoconstriction

Pretreatment Medications

Placement of an NGT is one of the most painful routine procedures performed in the ED. In nonemergency situations it is best practice to treat the patient with nasal vasoconstrictors and anesthetics before placing the tube.4

Application of lidocaine before inserting an NGT has been shown to significantly decrease pain during the procedure.5–7 Lidocaine can be delivered as viscous, nebulized, or atomized preparations. Application of viscous lidocaine to the nasal passage combined with lidocaine spray applied to the posterior pharynx has been shown to be superior to other forms of anesthetics when placing an NGT or transnasal bronchoscope.6,8 However, no definitive study or review article has determined the best concentration, form, or dose of lidocaine to use.7

lidocaine options

• Viscous lidocaine—5 to 10 mL of 2% lidocaine applied to an adult nasal passage 0 to 5 minutes before NGT placement combined with lidocaine spray applied to the posterior pharynx.6,8,9 Introduce 3 mL of 2% viscous lidocaine into the nostril and then have the patient snort the medication.

• Nebulized lidocaine—2.5 to 5 mL of 4% lidocaine nebulized before insertion via face mask.10

• Atomized lidocaine—1.5 mL of 4% lidocaine or two puffs of 10% lidocaine atomized to the nasal passage.6,11

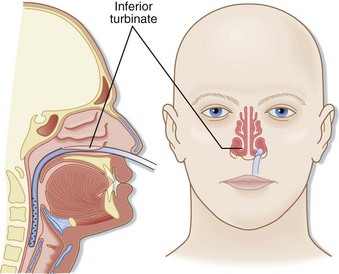

4 Insertion of the Tube

The tube is inserted into the naris along the floor of the nose inferior to the lower turbinates. The tube should be inserted at close to a 90-degree angle with the face and directed parallel to the floor of the nose (posteriorly), not cephalad (Fig. 46.2). Gentle pressure should be used to advance the tube past the nasopharynx and into the oropharynx. Once the tube is in the posterior pharynx, the patient is asked to swallow or take a sip of water to aid in smooth passage of the tube into the esophagus. The tube is then quickly advanced to the premeasured length to minimize discomfort. Care should be taken to not use excessive force when placing an NGT to avoid mucosal injury.

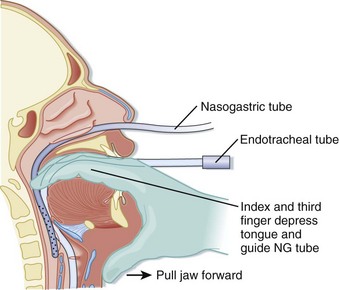

Alternative Approaches with Difficult Tube Insertions

Alternatively, digital placement of an NGT can be accomplished in a paralyzed, sedated, and intubated patient. The emergency physician places the second and third fingers in the posterior pharynx of the patient and depresses the tongue. The tube is passed through the nose into the posterior pharynx with the fingers in the pharynx to direct the tube into proper location (Fig. 46.3).2

Verifying Tube Placement

• Insufflation of air causing or resulting in borborygmi (gurgling) sounds heard over the epigastrium verifies that the tube is in the stomach.

• Aspiration of gastric fluid; a pH less than 4 is correlated with a 95% likelihood that the tip of the tube is in the stomach.

• In a conscious patient, normal clear speech without coughing is suggestive of proper tube placement.12

Complications

Placement of an NGT has a complication rate between 0.5% and 1.5%. Common complications are as follows13:

• Tracheal or bronchial placement

• Esophageal or pharyngeal perforation

• Esophageal obstruction or rupture

• Gastrothorax and tension gastrothorax

• Pulmonary aspiration; the NGT may induce a hypersalivation response, a depressed cough reflex, or mechanical or physiologic impairment of the glottis14–16

Transabdominal Feeding Tubes

Feeding tubes are placed to provide long-term nutritional support. They are classified both by the location of their terminal lumen and by the method of placement. Gastrostomy tubes have a terminal lumen located within the stomach and are now typically placed via a percutaneous endoscopic technique; they are thus called PEG (percutaneous, endoscopically placed gastrostomy) tubes (Fig. 46.4). Several manufacturers make various types of PEG tubes. The other most frequently encountered feeding tube is a J tube, or jejunostomy tube. Such tubes are longer, smaller-caliber tubes that terminate in the jejunum. Unlike a gastrostomy tube, a J tube does not have an inflated balloon on its terminal end.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree