26 Eye Emergencies

• Eye emergencies can be classified into three major types: the red eye, the painful eye, and visual loss.

• Nausea and vomiting may be the only symptoms of acute angle-closure glaucoma, especially in elderly patients.

• Topical anesthetics should not be prescribed for a painful eye disorder because their use may lead to corneal ulcers.

• Close follow-up with an ophthalmologist should be recommended for most eye emergencies.

Epidemiology

Approximately 2% of emergency department (ED) visits involve complaints associated with the eye or vision.1 Eye injuries account for 3.5% of all occupational injuries in the United States, and about 2000 U.S. workers injure their eyes each day.2 Eye emergencies can be categorized as the red eye, the painful eye, and visual loss. This chapter discusses the various disorders that fall into each category. Table 26.1 summarizes the differential diagnosis and priority actions to be taken for any patient arriving at the ED with an eye complaint.

Table 26.1 Differential Diagnosis and Priority Actions for Eye Complaints in the Emergency Department

| Eye Pain? | |

| Decreased Visual Acuity? | |

| Eye Trauma? | |

| Red Eye? | |

Physiology

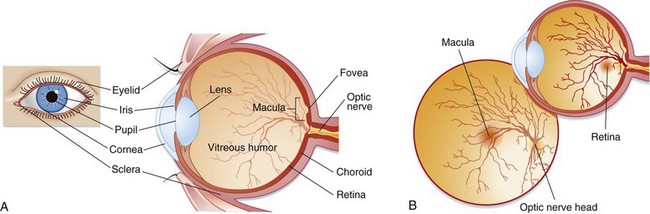

Light passes through the cornea and then through an opening in the iris, the pupil. The iris is responsible for controlling the amount of light that enters the eye by dilating and constricting the pupil. This light then reaches the lens, which refracts the light rays onto the retina. The anterior chamber is located between the lens and the cornea and contains aqueous humor, which is produced by the ciliary body. This fluid maintains pressure and provides nutrients to the lens and cornea. It is reabsorbed from the anterior chamber into the venous system through the canal of Schlemm. The vitreous chamber, located between the retina and the lens, contains a gelatinous fluid called vitreous humor. Light rays pass through the vitreous humor before reaching the retina. The retina lines the back of the eye and contains photoreceptor cells called rods and cones. Rods help vision in dim light, whereas cones aid light and color vision. The cones are located in the center of the retina in an area called the macula. The fovea is a small depression in the center of the macula that contains the highest concentration of cones. The optic nerve is located behind the retina and is responsible for transmitting signals from the photoreceptor cells to the brain (Fig. 26.1).

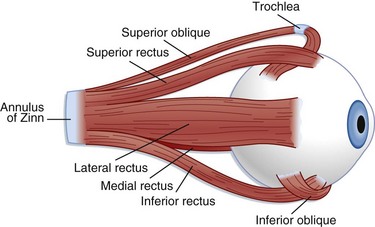

The extraocular muscles (Fig. 26.2) help in stabilization of the eye. Six extraocular muscles assist in horizontal, vertical, and rotational movement. These muscles are controlled by impulses from cranial nerves III, IV, and VI, which tell the muscles to relax or contract.

Glaucoma

Epidemiology

More than 3 million Americans suffer from glaucoma, the leading cause of preventable blindness in the United States.3 The term glaucoma refers to a group of disorders that damage the optic nerve and thereby lead to loss of vision. The two main classifications of glaucoma are open angle and angle closure. Acute angle-closure glaucoma is more common in white persons and women. Its peak incidence occurs between the ages of 55 and 70.4 African Americans, patients older than 65 years, and people with diabetes and ocular trauma are at increased risk for open-angle glaucoma. Differentiation between the two types of glaucoma lies in the mechanism of obstruction of outflow, as described later. Intraocular pressure (IOP) is determined by the rate of aqueous humor production relative to its outflow and removal. Normal IOP is between 10 and 20 mm Hg. This discussion focuses mainly on acute angle-closure glaucoma.

Central Retinal Artery Occlusion

Epidemiology

Retinal artery occlusion affects less than 1 per 100,000 persons annually.5,6 It is most commonly caused by an embolus from the carotid artery that lodges in a distal branch of the ophthalmic artery. Central retinal artery occlusion most commonly affects elderly patients and men. Although most emboli are formed from cholesterol, they may also be calcific, fat, or bacterial from cardiac valve vegetations.

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

Sudden, painless visual loss is the classic manifestation of central retinal artery occlusion. Sometimes patients report transient visual loss before complete compromise. The visual loss is usually profound. Examination can often elicit an afferent pupillary defect (when light is shined into the abnormal eye, the pupil of the affected eye paradoxically dilates instead of constricting). Funduscopic examination typically demonstrates a pale retina with a cherry-red spot at the fovea (Fig. 26.3). Complete evaluation involves auscultation of the carotid arteries for bruits, palpation of the temporal artery for tenderness, and cardiac auscultation and palpation of the pulse to detect atrial fibrillation.

Treatment

Other treatment options are intraarterial thrombolysis and hyperbaric oxygen; however, studies have shown limited improvement in visual outcome with early administration of both these treatment modalities.7–10 One retrospective study found that even with thrombolysis, vision did not improve to better than 20/300 in the affected eye.7 Another study investigated the outcomes of 32 patients with central retinal artery occlusion, 17 of whom underwent fibrinolysis.6 This study found that all but six of the treated patients reported improvement in their visual compromise but that only five of the untreated patients had any improvement. In this study, patients with a duration of symptoms of up to 24 hours were treated.

Central Retinal Vein Occlusion

Epidemiology

Patients older than 50 years who have cardiovascular disease, hypertension, glaucoma, venous stasis, hypercoagulable conditions, collagen vascular diseases, or diabetes are at risk for central retinal vein occlusion.1

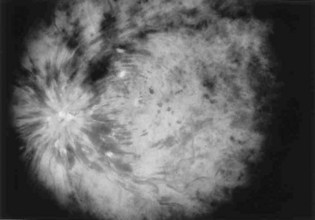

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

Typically, patients with ischemic retinal vein occlusion report an acute and relatively profound decrease in visual acuity. Those with the nonischemic type have progressively blurry vision that is worse in the morning. An afferent pupillary defect is found in the ischemic type. Funduscopic examination shows an edematous optic disk and macular, dilated retinal veins, retinal hemorrhage, and cotton-wool spots. Sometimes these findings are called the “blood and thunder” appearance of the fundus (Fig. 26.4).

Treatment

Although no specific treatment is available, a number of interventions have been proposed and practiced.11,12 However, these interventions have not been based on evidence of efficacy. Laser photocoagulation, for example, cauterizes leaking vessels with the aim of halting further visual loss. This procedure can be especially helpful for branch retinal vein occlusion. With nonischemic vein occlusion, attempts to reduce macular edema can be helpful. The reduction is accomplished with the administration of topical corticosteroids. Studies have been conducted to determine the benefit of steroids in treating both forms of retinal vein occlusion. Jonas et al.11 conducted a prospective, comparative, nonrandomized clinical interventional study to evaluate the visual outcomes in 32 patients with central retinal vein occlusion after intravitreal administration of triamcinolone acetate. The study included patients with both the ischemic and nonischemic forms of retinal vein occlusion. These researchers found that the medication resulted in temporary (up to 3 months) improvement in visual outcome but also raised IOP. Anticoagulants are not recommended because they may propagate hemorrhage.

Optic Neuritis

Treatment and Disposition

Ophthalmologic and neurologic consultation should be obtained if optic neuritis is suspected. Approximately 31% of patients with optic neuritis have a recurrence within 10 years of the initial episode.13 The goals of treatment are to restore visual acuity and prevent propagation of the underlying disease process. The Optic Neuritis Treatment Trial was a randomized, 15-center clinical trial involving 457 patients that was performed to evaluate both the benefit of corticosteroid treatment of optic neuritis and the relationship of this entity to multiple sclerosis. Use of intravenous steroids in conjunction with oral steroids reduced the short-term risk for the development of multiple sclerosis as determined by MRI evaluation. No long-term immunity from or benefit for multiple sclerosis was reported, however. The study concluded that although intravenous steroids have only minimal, if any effect on the patient’s ultimate visual acuity, they do expedite recovery from optic neuritis. Use of oral steroids alone is associated with a higher recurrence rate of optic neuritis. The dosage regimen recommended on the basis of the study results was methylprednisolone, 250 mg intravenously every 6 hours for 3 days, followed by prednisone, 1 mg/kg/day orally for 11 days.14

Retinal Detachment

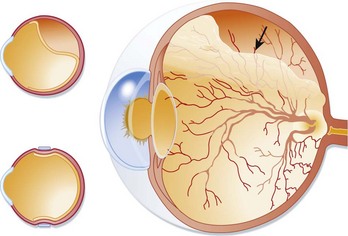

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

Retinal detachment can occasionally be asymptomatic. More commonly, patients complain of flashes of light, floaters, or fine dots or cobwebs in their visual fields. Generally, a new onset of floaters associated with flashing lights is indicative of retinal detachment unless proved otherwise. Visual acuity correlates with the extent of macular involvement and can be minimally changed to severely decreased. The loss of vision is usually sudden in onset and starts peripherally, with propagation to the central visual field. The visual loss is commonly described as a filmy, cloudy, or curtainlike appearance. Visual field cuts relate to the location of the retinal detachment, and an afferent pupillary defect occurs if the detachment is large enough. Retinal detachment is painless. On examination, the detached retina may appear gray or translucent or may seem out of focus (Fig. 26.5). Retinal folds may be seen. The visual field defects are variable, depending on the involvement of the retina and macula. Bedside ED ultrasonography has been shown to be helpful in confirming the presence of retinal detachment.15 Left untreated, all cases of retinal detachment progress to involve the macula and result in complete loss of vision in the affected eye.