Esophagus, Stomach, and Duodenum

Louis H. Alarcon

Ryan M. Levy

James D. Luketich

The focus of the chapter is non-traumatic diseases that cause inflammation, perforation, or obstruction of the upper gastrointestinal tract, often requiring operative intervention. A key principle is the importance of prompt recognition of the patient who requires immediate surgical intervention, rather than expending time and effort on diagnosis of the specific pathology in this patient. Delayed management is associated with increased morbidity and mortality. The evaluation and management of gastrointestinal bleeding is discussed in Chapter 47.

I. Esophageal Perforation

Clinical presentation. Perforation of the esophagus is seen in many clinical scenarios.

Boerhaave’s syndrome is post-emetic esophageal perforation. This may occur in patients with previously normal esophageal function or patients with underlying esophageal pathology or motor disorders. The pathophysiology involves a violent episode of vomiting or retching that results in a rapid increase in intraluminal pressure within the esophagus. Most commonly, the perforation is seen in the lower third of the esophagus.

The esophagus can be perforated during upper endoscopy.

Typically, when encountered in a patient with normal esophageal function, perforation occurs in the cervical esophagus. This is a result of failure to navigate the cricopharyngeus muscle that guards the upper portion of the esophagus. Aggressive blind passage through this region of the esophagus can result in passage of the endoscope through the pyriform sinus. The increasing use of side-viewing endoscopic ultrasound and transesophageal echocardiography probes that are larger and more difficult to pass places this anatomic region at increased risk for injury.

Perforation can occur in patients with esophageal pathology during upper endoscopy.

In patients with Zenker’s diverticulum, failure to negotiate past the hypertensive cricopharyngeus can lead to perforation of the pyriform sinus, as described previously. In addition, inadvertent forcible passage of the scope within Zenker’s diverticulum can lead to perforation of the diverticulum.

Perforation during endoscopy for obstructing malignancies can occur proximal to the obstruction or within the obstructing lesion.

Perforation can occur when attempting to pass the endoscope across a tortuous or strictured cervical esophagus or hypopharynx, such as those seen in patients with a history of head and neck cancer or irradiation.

On occasion, perforation occurs with endoscopic interventional procedures. Patients with achalasia who are being treated with esophageal dilation or botulinum injection can suffer from distal esophageal perforation. Perforation can be seen in the setting of laser therapy, sclerotherapy, or photodynamic therapy, or retrieval of foreign objects. In addition, the foreign object itself may perforate the esophagus.

Perforation of the esophagus may occur perioperatively. Manipulation of the esophagus, particularly in procedures such as fundoplication or Heller myotomy, can result in delayed presentation of esophageal perforation.

Perforation can occur with ingestion of caustic materials. The esophagus is particularly susceptible to ingestion of alkali but relatively immune to ingestion of

acidic material. Lye ingestion is the most common caustic agent causing perforation, while standard household bleach does not cause significant alkali injury. Ingestion of lye can lead to both acute and subacute full-thickness necrosis and subsequent perforation of the entire length of the esophagus. Those who survive the acute event are at risk for recalcitrant stricture. In addition, there is increased long-term risk of malignancy (squamous cell carcinomas).

Tumor necrosis can extend the full thickness of the esophageal wall and cause spontaneous or post-treatment perforation. This is a particular concern after photodynamic therapy ablation of an obstructing esophageal malignancy or external beam radiation therapy in the setting of an esophageal stent.

Perforation after penetrating or blunt trauma can occur anywhere along the entire length of the esophagus depending on the path of the offending agent. The cervical esophagus is particularly prone to injuries sustained from knife or gunshot wounds in the neck. Esophageal perforation secondary to blunt trauma associated with motor vehicle accidents is less common.

Evaluation

Clinically, the patient may present with neck, chest, or abdominal pain. The patient may have an acute abdomen or be moribund. The physical examination may reveal neck or upper body crepitus secondary to subcutaneous emphysema. The patient with associated mediastinitis, empyema, or frank peritonitis may be hemodynamically unstable.

Common initial tests include an electrocardiogram, complete blood count with differential, coagulation profile, and electrolyte assay although none are diagnostic. It is wise to type and screen in preparation for surgery.

Imaging

A chest radiograph (CXR) is the first radiographic examination. This may reveal an associated pleural effusion, hydropneumothorax, or pneumoperitoneum.

CT of the chest and abdomen is usually next, with oral contrast when possible. This may reveal pneumomediastinum, pneumoperitoneum, or extraluminal contrast.

Esophagogram with water-soluble contrast followed by thin dilute barium to identify the location of the perforation is frequently used to guide management as well. The esophagogram may be used in lieu of CT or as an adjunct. The contrast esophagogram may demonstrate whether the leak is uncontained, contained, or drains spontaneously back into the lumen of the esophagus. Special care should be taken when an associated obstruction is suspected to prevent aspiration of the water-soluble contrast. In patients with suspected esophageal obstruction, do not use gastrografin or water-soluble contrast, which leads to severe chemical pneumonitis if aspirated.

In stable patients with contained leaks being managed nonoperatively, avoid endoscopy and the risk of worsening any perforation. Insufflation during endoscopy may blow out a contained leak and necessitate surgery.

Management begins with resuscitative measures. Securing the airway, if necessary, along with volume resuscitation and broad-spectrum antibiotics against enteric organisms and anaerobes. A urinary catheter aids assessment of volume repletion and renal function.

In a patient who is hemodynamically stable, follow the imaging sequence above (CXR, CT, contrast esophagogram).

In a stable patient, if the leak is contained or drains spontaneously back into the esophagus, nonoperative management with IV fluids and antibiotics may be sufficient. Such management is predicated on a nontoxic patient physiology and complete drainage of any associated fluid collections, such as pleural effusions. These patients should be kept fasted initially and have serial radiographs over the next 48 to 72 hours. A repeat CT is important to ensure that no new, undrained fluid collections have developed; if they occur, they must be drained or operative intervention planned. A repeat contrast esophagogram should also be obtained; if no leak or perforation, liquids by mouth may be started. If the patient deteriorates during nonoperative management, operate.

Surgery for esophageal perforation is classified into four broad categories: Repair, resection, diversion, or wide drainage. Regardless of the type of surgical intervention, upper endoscopy at the time of surgery assesses mucosal viability and the integrity of the repair.

If the patient is stable, attempt primary repair regardless of time of presentation and debride nonviable and necrotic tissue. A two-layer repair (mucosa to mucosa and muscle to muscle) over a 42 Fr bougie or a gastroscope is recommended. It may help to buttress the repair with soft tissue such as intercostal muscle, serratus muscle, omentum, or pericardial fat. Place drains in the proximity of the repair. If the viability or quality of the esophageal tissue is marginal, repair over a T-tube (size 14 F), in addition to placement of peri-esophageal drains. Often, a decompressive gastrostomy tube and a feeding jejunostomy tube are good early options.

Perforation in the setting of dilation or botulinum toxin injection for achalasia may be repaired primarily. Typically, the perforation occurs at the site of or just above the hypertensive lower esophageal sphincter. A Heller myotomy needs to be performed 180 degrees away from the site of perforation. The myotomy needs to be at least 6 cm long and extend to the very proximal gastric cardia. In addition, a partial fundoplication (Toupet or Dor fundoplication) should be performed in conjunction with the repair and myotomy.

In patients with esophageal malignancy, end-stage achalasia, or caustic injury with esophageal necrosis, do an esophagectomy if the patient is stable. Drainage of the mediastinum with large-bore chest tubes or soft drains (e.g., Jackson-Pratt drain) is needed if there is extensive soilage.

Diversion is a good option in patients where repair or resection is not possible either because of anatomic considerations (e.g., locally unresectable esophageal cancer) or who are unstable. In addition, as with caustic injuries, the final proximal and distal extent of the necrotic injury may not be readily apparent. In particular, this is an issue when there is necrosis of the stomach that may need to be utilized as the conduit for reconstruction. Diversion can be accomplished via a lateral cervical esophagostomy. However, it is preferable to dissect and mobilize the intrathoracic esophagus and then create an end cervical esophagostomy below the clavicle via a left-neck approach. This allows for easier management of the stoma appliance. In addition, it allows for a longer segment of proximal esophagus for potential future reconstruction. A gastrostomy and/or jejunostomy tube should be placed. Wide drainage with large-bore tubes should be placed at the site of perforation.

In a patient who is in extremis, emergent operation is required. Wide debridement and drainage may be the only option. This maneuver may allow the patient to stabilize enough to undergo repair or resection at a later date. A nasogastric tube should be placed with the tip in the distal esophagus to allow drainage of saliva within the esophagus. Place a decompressive gastrostomy tube to prevent reflux of gastric contents and a feeding jejunostomy placed for enteral access.

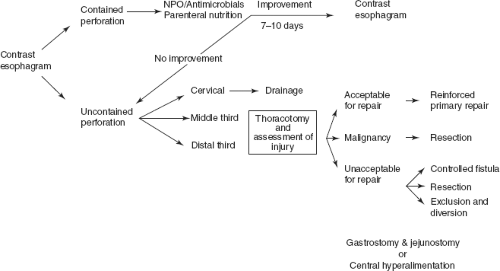

Debridement and drainage are appropriate and sufficient for perforation of the cervical esophagus. In these patients, be concerned about extension of soilage from the cervical area into the mediastinum. Drainage of the mediastinum in these cases can be accomplished through the cervical incision. Rarely, video-assisted thoracoscopy or even thoracotomy may be necessary to fully drain the superior mediastinum. Figure 51-1 describes an algorithm for the management of esophageal perforation.

II. Esophageal Obstruction

Presentation

Obstruction of the esophagus can occur in the setting of primary esophageal pathology, such as malignancy, benign strictures, or esophageal dysmotility such as achalasia. In addition, obstruction of the esophagus can occur in patients with

a normal esophagus, often in children or those with psychiatric illness where ingestion of foreign objects is common. Another common group includes adult patients who have failed to masticate a large food bolus (e.g., meat).

Obstruction of the esophagus can cause respiratory compromise secondary to aspiration of retained saliva. Obstruction associated with a chronic process is often coupled with a dilated esophagus. The dilated esophagus may have a pool of retained saliva and food debris, which may lead to an acute obstruction of the narrowed lumen. Clinically, a patient with an obstructed esophagus may present with substernal pain, especially in a patient without previous esophageal pathology. Hypersalivation and aspiration may occur. In severe cases, a totally obstructed esophagus may present with respiratory compromise or inability to protect the airway.

Obstruction of the esophagus can occur at multiple points along the esophagus. In an otherwise normal esophagus, three areas are narrowed in caliber and are the usual sites where food or a foreign body can lodge: The cricopharyngeus, mid-esophagus (where the aortic arch indents the esophagus), or the lower esophageal sphincter.

Evaluation and management

Seek key historical features noted above. In patients with a history of a known obstructing lesion, such as malignancy, achalasia, or stricture, there may be a large volume of pooled secretions and food debris. In patients with foreign body ingestion, it is important to determine whether sharp objects that may perforate the esophagus are present.

Assess the airway and intubate if any concerns for aspiration exist.

In patients who are stable, do a contrast esophagogram. The risk of aspiration during the study must be assessed, notably by evidence of pooling or any airway difficulty present. If there is any doubt about the risk of aspiration, forego the study. Contrast esophagogram may demonstrate a previously undiagnosed esophageal lesion, identify the level of obstruction, and also exclude perforation of the esophagus. Use dilute barium for this esophagogram.

Flexible endoscopy under general anesthesia is recommended next or when the esophagram cannot be safely done. Once the impacted food or foreign body is retrieved, do a more thorough assessment of the esophagus. Biopsy any suspicious lesions. Endoscopic dilation can relieve stricture or malignancy. In patients with achalasia, a delayed and elective Heller myotomy is best, reserving dilation and botulinum toxin injection for those who are not a candidate for myotomy.

Endoscopy under general anesthesia will decrease risk of inadvertent aspiration.

Large-volume lavage of the esophagus with a large-bore tube may be necessary to irrigate the impacted material.

When flexible esophagoscopy is unsuccessful, rigid esophagoscopy under general anesthesia may be necessary. Avoid inadvertent perforation during rigid esophagoscopy.

III. Chemical Burns/Corrosive Injuries

Acidic or alkali ingestion can result in a burn to the esophagus, stomach, and duodenum. Alkali is the more common agent, notably lye (but not household bleach, which does not cause important injury). Ingestion occurs most often in children and is accidental. In adults, ingestion is often part of a suicide attempt. Although the site of injury can be anywhere in the esophagus, the lower esophagus is often more injured due to a greater contact time with the offending agent. Burns of the mouth, pharynx, epiglottis, or larynx may complicate the presentation and result in respiratory compromise.

Conservative management consists of intravenous fluid resuscitation, nothing by mouth, and pain control.

Immediate esophagoscopy is not indicated unless perforation is suspected or the patient demonstrates evidence of shock. Esophagoscopy is recommended after 48 hours. The scope is passed to the first area of burn. If severe injury is encountered,

do not pass the scope further. Perform a complete endoscopy in the setting of minor burns or erythema. Repeat endoscopy is indicated 3 to 4 weeks later. A contrast esophagogram can detect delayed strictures.

Surgical intervention is seldom necessary unless a full-thickness injury occurs. This may necessitate esophagectomy or esophageal exclusion and diversion.

The role of steroids in the treatment of corrosive esophageal injuries is controversial. No evidence supports the routine use of steroids in this setting. Careful endoscopic dilation of the stricture may begin 4 weeks after caustic ingestion. This may need to be repeated.

IV. Peptic Ulcer Disease (PUD)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree