Type

Causes

Clinical findings

Anatomic

External compression from an aberrant right subclavian artery

Pyriform sinus

Singing, yelling, trumpet playing, recent endoscopy

Marked mediastinal and cervical subcutaneous emphysema

Anastomotic

Leakage at or near the site of a surgical anastomosis

History of surgically created esophageal anastomosis

Boerhaave’s

Vomiting, straining, retching, weight lifting, hyperemesis, seizures causing a full-thickness tear at the gastroesophageal junction

Characteristic longitudinal tear on the left side of the esophagus, typically in the distal 1/3 segment

Mucosal defect typically longer than muscular defect

Iatrogenic

Endoscopic: Ablation, dilation, sclerotherapy, instrumentation

Surgical: Esophageal surgery, foregut cyst decortication, spine surgery

Recent history of surgery or endoscopy

Traumatic

Penetrating or blunt trauma to neck or torso

Strong association with neck hyperextension

Cancer

Perforation of an esophageal tumor

Erosion of surrounding tumor through esophageal wall

Gas near or abutting the tumor on imaging

Paraesophageal hernia

Incarceration with necrosis of the distal esophagus

Evidence of left pleural effusion or abdominal fluid on imaging studies

Foreign body

Ingestion of a substance (i.e., chicken bone) that becomes lodged

Impaction at a stricture

Esophageal webs

Eosinophilic esophagitis

Upper esophageal impaction at the sphincter

Esophagitis

Inflammation and erosion of ulceration

Zollinger–Ellison syndrome

Barrett’s ulcer

Infection (Candida, Herpes simplex, viruses, CMV)

Immunocompromised patient

Ingestion

Ingestion of caustic substance

Drug ingestion/impaction

Tetracycline

Potassium

Quinidine

NSAIDS

Sustained-release formulations

Spontaneous esophageal perforation, commonly known as Boerhaave’s syndrome, results from abrupt increases in intraesophageal pressure. It was originally described by Herman Boerhaave in 1724, in a pamphlet detailing his postmortem observations of Baron de Wassenaer, the Grand Admiral of Holland. Though Boerhaave’s syndrome has historically come to be linked with violent emesis following unrestrained imbibition or food consumption, the Baron suffered a fatal esophageal rupture as a result of self-induced vomiting in an attempt to relieve the discomfort of indigestion [4]. Spontaneous perforations associated with weight lifting, childbirth, seizures, and defecation have been reported, and likely bear a similar physiologic origin.

The superficial course of both the cervical and thoracic esophagus renders them susceptible to injury from penetrating trauma. Additionally, gunshot wounds can also inflict indirect thermal injury easily missed at initial examination that can subsequently become the site of a rupture. Esophageal disruption can likewise occur in the setting of blunt traumatic injuries. Putative mechanisms include torsive and stretching forces, as well as rapid acceleration with injury occurring at fixed points. Ingestion of caustic materials, broadly classified as acidic or alkaline, can also result in esophageal perforation. This is most common with alkaline consumption, as these agents are both more palatable and cause a liquefactive necrosis with a propensity for transmural progression of the injury. Although acid ingestion results in a coagulative necrosis with less potential for penetration, perforation can occur.

Acute inflammation and infection can also lead to perforation of a weakened esophageal wall, particularly in the immunocompromised patient. One noteworthy etiology is eosinophilic esophagitis, characterized by unexplained focal penetration of eosinophils. Multiple reports of spontaneous perforation in this setting exist [5, 6].

Presentation

The clinical signs and symptoms of esophageal perforation are largely dependent upon the anatomic location of the defect. Fever, tachycardia, tachypnea, dyspnea, shock, and leukocytosis are frequently present regardless of the site of the injury. Crepitus, indicative of underlying subcutaneous emphysema, suggests a perforation in the neck or pyriform sinus. Additionally, these patients may describe neck pain of varying severity, vocal disturbances classically described as a prominent “nasal” tonality, dysphagia, or bleeding through the mouth. Perforations of the thoracic or abdominal esophagus often result in vomiting, chest and/or back pain, dyspnea, dysphagia, and bleeding. In addition, defects of the intra-abdominal esophagus commonly cause abdominal pain and distention. “Mackler’s Triad” denotes the classic presenting syndrome of patients with spontaneous esophageal rupture, and includes vomiting, lower chest pain, and subcutaneous emphysema. The Anderson Triad, likewise suggestive of spontaneous esophageal rupture, includes subcutaneous emphysema, rapid respirations, and abdominal rigidity.

Evaluation

Evaluation of the patient with suspected esophageal perforation begins with a detailed history and physical examination. Particular attention should be given to any recent history of instrumentation or trauma to the neck or torso, quantitative and qualitative assessment of recent food and liquid consumption, evidence of malignancy such as recent weight loss or dysphagia, or any signs of progressing sepsis. Hemodynamic instability should be immediately addressed with placement of large-bore intravenous catheters and fluid administration. Once esophageal perforation is suspected, antero-posterior and lateral upright chest and abdominal radiographs should be obtained without delay. Radiographic findings suspicious for perforation include subcutaneous emphysema, the presence of pleural effusions, pneumomediastinum, hydro/pneumothorax, and pleural thickening. Radiographs are particularly useful in the setting of suspected iatrogenic perforation, as they may prove diagnostic in up to 80% of these patients. Furthermore, radiographs have utility in terms of localization of the defect; a right pleural effusion suggests a mid-esophageal perforation, while a left effusion portends a lower esophageal lesion.

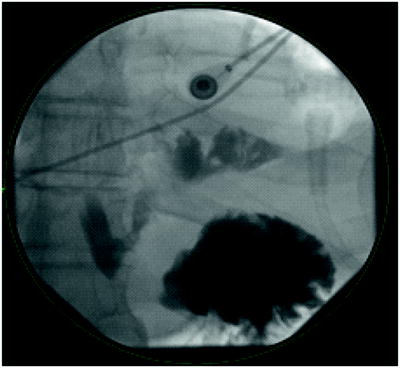

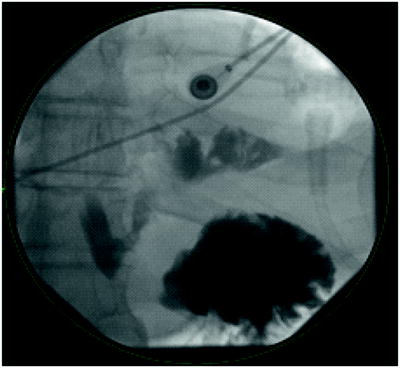

The gold standard for diagnosis of perforation is a contrast swallow study, done in the presence of the treating surgeon. Performed fluoroscopically, the patient should be oriented obliquely relative to the source and remain in a standing, semierect position, which will facilitate the detection of small leaks (Fig. 14.1 through Fig. 14.5). Given the risk of severe pneumonitis associated with gastrograffin aspiration, angiography agents are preferred. Barium use can complicate future imaging in the patient due to persistence of the substance in the esophagus for several days, and should only be used if an obvious perforation is not detected on initial swallow evaluation with a water-soluble contrast agent. Although essential in the initial evaluation of suspected esophageal perforation, the false negative rate of contrast radiography approaches thirty percent.

Fig. 14.1

Contrast esophagram of a Boerhaave perforation of the esophagus at the gastroesophageal junction resulting in left pleural contamination

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree