Epistaxis

Trevor J. Lewis

Epistaxis is a frequent problem encountered by the emergency physician, accounting for approximately 1 in 200 emergency department (ED) visits in the United States (1). The incidence is bimodal, with peaks at ages younger than 10 and between 70 and 79 years of age (2). The higher incidence in children is attributed to local digital trauma in combination with reduced humidity during winter months (1,3). Pediatric epistaxis is usually benign and treated with local measures (4). Elderly patients are more likely to require invasive therapy and admission, because of both systemic causes of epistaxis and increased endothelial degeneration (3). Epistaxis is rarely life-threatening, and a majority of patients can be managed definitively by the emergency physician. When bleeding is not controlled by local measures, the source is usually posterior, and urgent otolaryngology consultation is required. Most posterior bleeds occur in older patients with the mean age of occurrence reported as 64 years of age (5).

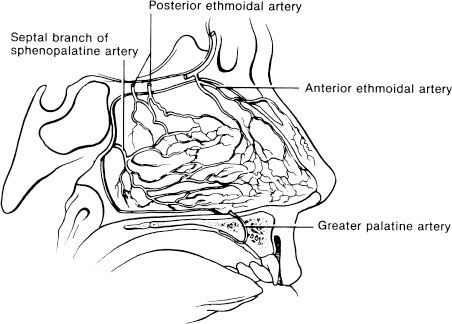

The vascular supply to the nose is extensive, consistent with its function of warming and humidifying air. The blood supply to the nasal mucosa arises from the internal maxillary and facial arteries via the external carotid as well as from the posterior and anterior ethmoidal arteries via the internal carotid (6). The sphenopalatine artery, the terminal branch of the maxillary artery, supplies the lateral nasal wall below the middle turbinates and is the vessel responsible for most posterior epistaxis (7). The superior labial artery and greater palatine artery, terminal braches of the facial and maxillary arteries, respectively, supply the anterior portions of the septum and floor of the nasal cavity. The anterior and posterior ethmoidal arteries supply both the septum and the lateral aspect of the nose superiorly. The confluence of these terminal arteries is referred to as Kiesselbach plexus or Little area. The majority of anterior nosebleeds occur in this area (Fig. 69.1).

FIGURE 69.1 Blood supply to Kiesselbach plexus.

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

Epistaxis usually presents as spontaneous unilateral bleeding from a discrete lesion. Bilateral epistaxis is more commonly due to trauma or a posterior source of bleeding. Approximately 90% of nosebleeds are anterior, which means the bleeding source can be visualized in the anterior portion of the nasopharynx. The remaining 10% are posterior hemorrhages, in which a bleeding source is not directly visible. Posterior bleeds may present with nausea, hematemesis, anemia, hemoptysis, or melena (7) or may present with sudden copious bleeding due to involvement of larger vessels.

Patients with an underlying coagulopathy may present with other manifestations of bleeding such as bruising, petechiae, bleeding gums, hematuria, or gastrointestinal bleeding. Patients with a significant amount of blood loss may present with signs and symptoms of hypovolemia such as lightheadedness, fatigue, tachycardia, or hypotension.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Epistaxis usually occurs from an interaction of factors that damage the superficial blood vessels of the nasal mucosa. The differential diagnosis includes both local and systemic causes, although the majority of cases are idiopathic (8). Local causes include direct facial trauma, nose picking (epistaxis digitorum), and chemical nasal irritants such as cigarette smoke, cocaine, and steroid nasal sprays. Epistaxis may be due to inflammatory disorders such as upper-respiratory infection, sinusitis, and allergic rhinitis. Environmental causes such as dry air during the winter months have been correlated with higher rates of admission for epistaxis (9). Other causes include foreign bodies (especially in children, the developmentally delayed, and elderly institutionalized patients), iatrogenic causes such as nasogastric and nasotracheal intubation, surgical complications, and overzealous treatment of self-limited hemorrhage.

Hypertension has been cited as a cause of epistaxis, but the relationship is controversial. Although studies have shown a higher prevalence of hypertension in epistaxis it is postulated that the sight of blood may cause a hypertensive or “white coat” response (8). Many hereditary bleeding disorders can present with epistaxis, including hemophilia, von Willebrand disease, and thrombocytopenia. Heavy alcohol use and a history of renal failure also increase the risk of epistaxis.

Numerous medications increase the risk of epistaxis via inhibition of normal clotting mechanisms. The most common class is nonsteroidal agents (including aspirin), which interfere with the cyclooxygenase pathway and inhibit platelet aggregation (6). Other commonly implicated medications include warfarin and other antithrombotic agents as well as antiplatelet medications. Many herbal supplements have anticoagulant properties including those that contain garlic, gingko, ginseng, and vitamin E (9).

Occasionally, patients present with massive epistaxis that is initially confused with hemoptysis or hematemesis. Blood from an episode of epistaxis that is swallowed or aspirated may further confuse the issue. If blood is coming from the nose and mouth and the source is unclear, the patient should be asked to sit upright, blow the nose, and rinse the mouth with water, and the oropharynx should be examined under suitable light. Blood dripping from the posterior nasopharynx confirms nasal hemorrhage. Table 69.1 lists some causes of epistaxis.

TABLE 69.1

Causes of Epistaxis

ED EVALUATION

Initial evaluation of the patient with epistaxis should focus on control of the bleeding to facilitate a directed history and physical examination and to alleviate the patient’s anxiety. These measures should be initiated in triage and include the direct application of pressure by the thumb and index finger to the nasal alar area and the anterior septal area. The patient should be instructed to bend forward at the waist and spit out any blood that may pool in the throat. Swimmer’s clips may be applied to the nasal area to control hemorrhage (10). Patients presenting with massive epistaxis or unstable vital signs require immediate resuscitation and airway management as well as direct control of the bleeding site. This precludes a lengthy history and physical examination. Once the patient has been stabilized, a more detailed history and examination can be obtained.

The history should focus on the initial site, duration, and amount of bleeding. One should inquire about precipitating events, including trauma and intranasal medications (illicit or otherwise) (3) as well as previous episodes of bleeding and whether control was achieved at home or in the hospital. Episodes of hematemesis may suggest a posterior source of epistaxis. Easy bruising or prolonged bleeding after minor surgical procedures suggests the possibility of coagulopathy, and recurrent episodes of epistaxis, even if self-limited, should raise suspicion for intranasal tumors. Use of alcohol and medications, especially aspirin, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents, warfarin, or other antithrombotic or antiplatelet agents, should be noted, as these not only predispose to epistaxis but make treatment more difficult.

KEY TESTING

• Clotting studies (PT [INR], PTT): only for suspected bleeding diathesis, liver disease, or the anticoagulated patient (11,12).

• CBC, Platelets: if the patient relates a history of easy bruising, platelet disorder, neoplasia, or recent chemotherapy.

ED MANAGEMENT

The first priority in the management of epistaxis is to address the airway, breathing, and circulation (ABCs). Patients with unstable vital signs or severe hemorrhage should have intravenous access, as well as continuous cardiac monitoring and pulse oximetry. Massive hemorrhage may require endotracheal intubation to protect the airway and facilitate nasal packing. Elderly patients with massive bleeding may deteriorate rapidly, so aggressive resuscitation is vital (8). Rapid control of epistaxis that is associated with multiple trauma or significant facial injuries is best secured immediately with epistaxis balloons (13). This allows other life-threatening injuries to be addressed expeditiously. In patients with nontraumatic massive epistaxis, rather than making lengthy attempts at locating a bleeding source, the physician should proceed directly to packing with nasal balloons or tampons.

Most cases of epistaxis, however, are minor, and the episode frequently terminates with the proper application of pressure. When simple compression fails to stop the bleeding, the source of epistaxis must be located and then treated appropriately. Available treatments include topical vasoconstrictors, chemical or electrical cautery, nasal packing using prefabricated nasal tampons or epistaxis balloons, or traditional nasal packing. Every ED should have a prepackaged epistaxis tray or have key materials readily available (Table 69.2).

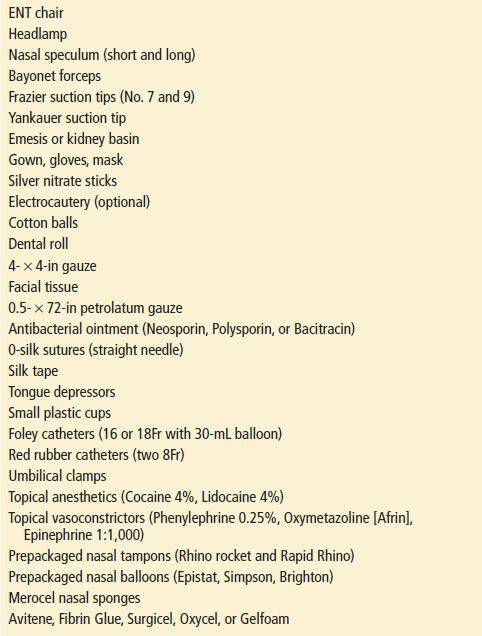

TABLE 69.2

Equipment Used for Management of Epistaxis