Fig. 41.1

MRI sagittal view of active infiltrative metastatic process as evidenced by STIR (short tau inversion recovery) images. STIR is an MRI image that causes loss of fat signal (bone marrow) from the relaxation properties of fat protons. STIR imaging is the most sensitive modality for visualization of edema and thus of acute fractures. MRI axial view in T2-weighted images shows invasive of the infiltrative metastatic process in the left pedicle. Images from personal library

Patient is scheduled for kyphoplasty. During procedure, after placement of the cannulas, the balloons are inflated in the targeted position.

Upon cement injection, it is clear that the posterior and superior walls are compromised, likely by the infiltrative metastatic process. Cement of a more paste-like consistency is deposited carefully to limit leak of the injectate toward the L3–L4 intervertebral disc or the epidural space. Posterior leak of cement in the epidural, although minimal, is noted. After the procedure, the patient’s back pain is resolved, but radicular pain increases with slight, new right quadriceps weakness 4+/5. A second radiographic image performed in the recovery room confirms tracking of the cement toward the posterior vertebral wall and shows only minimal epidural leak (Figs. 41.2 and 41.3).

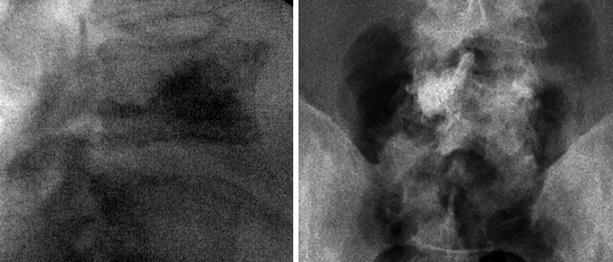

Fig. 41.2

Intraoperative fluoroscopy, lateral view, showing back track of cement toward the posterior elements; portable anteroposterior image does not clearly show cement leak. Images from personal library

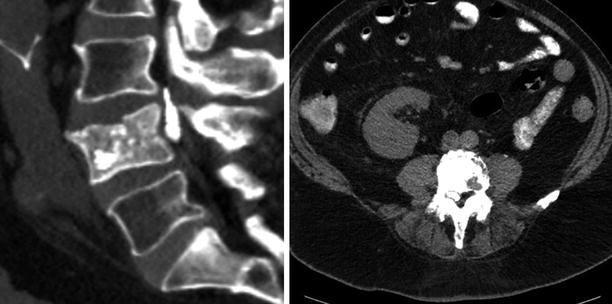

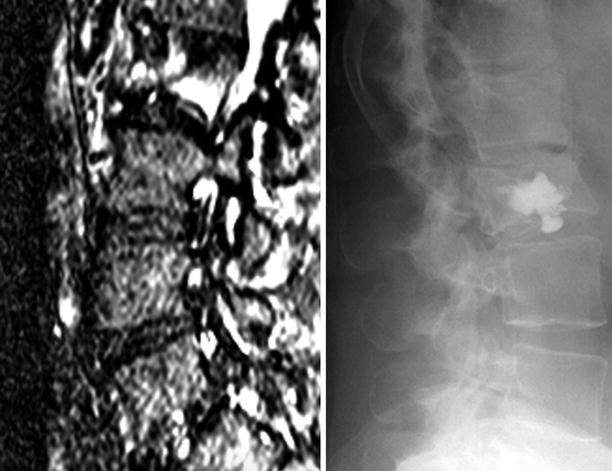

Fig. 41.3

Sagittal CT scan showing cement extravasation in the epidural space; after initial radiculitis, patient became asymptomatic after conservative treatment. In the axial view, the cement is seen toward the right L4 nerve root. Images from personal library

The patient is admitted for observation. His pain and weakness improve with an IV steroid taper, and a repeat MRI shows the right-sided cement leak that, together with underlying degenerative changes, contributes to the severity of right L4 foraminal stenosis. After a neurosurgery consultation, the patient is not considered a surgical candidate. The patient is discharged home, pain-free with a minor burning sensation in the right L4 distribution, and full motor strength. He is instructed to enroll in outpatient physical therapy. Following an aggressive physical therapy session, the patient complains of severe positional headache and severe back pain. When he returns to the hospital 2 days later, a CT of the lumbar spine with contrast is performed. It confirms a cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leak and fluid accumulation around the L4 vertebra, likely from dural proximity to the hardened cement during aggressive physical therapy. CT also confirms end plate depression of the vertebrae adjacent to the kyphoplasty-treated L4, likely from cement leak in the intervertebral disc. The patient’s headache responds well to a subsequent epidural blood patch, and his back pain improves with a conservative regimen and a back brace. He is able to enroll in a chemotherapy trial given his improved functional status after the interventions.

41.2 Case Discussion

41.2.1 Background

Vertebral compression fractures (VCFs) are associated with severe pain even with only minimal movement. In severe cases, pain from a VCF can be debilitating, leaving patients bedridden. The annual incidence of vertebral compression fractures has been reported to be 1.21% in women and 0.68% in men in those 50–79 years old, worsening with age and in women of all age groups [1]. When a VCF is identified, conservative management of pain is first attempted with medication, support braces, and in some cases gentle physical therapy. A normal course for a noncomplicated, stable vertebral compression fracture is gradual decrease of pain with healing of the fracture within 3 months. When pain is debilitating, functional capacity decreases, or when initial conservative measures are ineffective, interventional treatments such as vertebral augmentation procedures are involved earlier after the diagnosis.

The first percutaneous vertebroplasty was performed in France in 1984. The procedure has been improved since then. Although an excellent technique to treat VCF, vertebroplasty has been associated with several complications: adjacent-level fracture, pulmonary embolism, cement leak, systemic toxicity, infection, CSF leak, and epidural hematoma [2]. Recently, the advent of kyphoplasty has decreased the incidence of some of these complications such as cement extravasation [3].

With regard to technique, vertebroplasty and kyphoplasty are similar with a few notable exceptions. During vertebroplasty , fluoroscopic guidance is used to advance a needle into the cancellous bone of a vertebra to inject cement at the site of a fracture. In kyphoplasty, the needle is guided with the same technique, but a balloon is inflated in the vertebral body before injecting cement. Inflation is thought to compress the bone and create a cavity for injecting the cement under low pressure to minimize extravasation [4]. If the working kyphoplasty cannula and balloon are close to a compromised wall of a vertebra, an “egg shell technique” recreates the defected wall. Details of this technique are described later in this chapter.

Currently, polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA) is widely accepted as the standard cement type for both kyphoplasty and vertebroplasty. In some studies that have compared PMMA with calcium phosphate cement (CPC), loss of correction at 6 weeks was found on radiographic images in CPC compared to PMMA. CPC may have lower resistance to flexing, tractive, and sheer forces than PMMA. In burst fractures, CPC had a higher risk of cement failure, and patients’ pain scores approached preoperative levels after 1 year. With PMMA pain levels were lessened 1 year post-procedure [5]. Other studies argue that CPC is equally safe and effective, but because there is no literature to date proving its superiority to PMMA, PMMA remains the standard cement used [6].

Kyphoplasty also may have the added benefit of correcting prevalent kyphosis. A VCF follows an increase of anterior column load in response to hyperflexion forces that ultimately contribute to the progressing kyphosis often present in VCFs. With the added benefit of “fracture reduction” and kyphosis correction, kyphoplasty may offer an advantage over vertebroplasty in select cases [7]. Thus far, kyphoplasty has been successfully utilized by practitioners in thousands of patients who have improvement in short-term pain, quality of life, and function [8]. Improvements in pulmonary function also have been noted with respect to forced vital capacity and maximum voluntary ventilation [9]. Based on a comparison of transcortical and vascular extravasation of contrast, the risk of cement extravasation is lower with kyphoplasty than with vertebroplasty [3].

The two most common causes of vertebral compression fractures are osteoporosis and malignancy. Symptoms are almost indistinguishable between the two forms, but they differ depending on a patient’s medical history. A diagnosis of either osteoporosis or cancer is helpful in determining the type of fracture. Risk factors for osteoporotic fractures include alcohol or tobacco use, early menopause, dementia, frailty, and vitamin D deficiency [10]. Osteoporotic fracture is by far the more common of the two, often presenting after trivial events such as lifting objects, a vigorous sneeze, or turning in bed especially in cases of severe disease [11]. In moderate osteoporosis, trauma after falling off a chair or tripping can precipitate fracture. For patients younger than age 55, undiagnosed malignancy also should be considered [11]. During a vertebral augmentation procedure, the diagnosis is confirmed with an intraoperative bone biopsy. MRI distinguishes an osteoporotic from a malignant compression fracture. Studies of imaging have reported 100% sensitivity and 93% specificity for diagnosing metastatic compression fractures [12]. Lesions on the convex posterior border of vertebral bodies, abnormal signal intensity of the pedicle of the posterior element, epidural extension, encasing epidural mass, focal paraspinal mass, and other spinal metastases suggest a metastatic compression fracture.

Low signal intensity band on T1- and T2-weighted images, spared normal bone marrow signal intensity of vertebral body, retropulsion of posterior bone fragment, and multiple compression fractures suggest an osteoporotic compression fracture [12]. Adding axial diffusion-weighted imaging to standard spine MRI improves diagnostic accuracy in osteoporotic and malignant compression fractures [13]. For patients with osteoporotic VCF, the risk factors for developing more fractures are smoking, female gender, and history of treated or untreated VCF [14]. Indications for treatment of both types of fractures are pain refractory to conservative measures, but some patients with malignant fractures may have a better prognosis with radiation therapy.

41.3 Cement Extravasation

Despite advancements in vertebral augmentation techniques, the procedures are not risk-free. Rates of cement extravasation in kyphoplasty may be higher than originally postulated. Many case reports of significant spinal cord injury and nerve damage have been linked to vertebroplasty; recently, several reports document injury with kyphoplasty as well. In a study that reviewed 100 radiographs of consecutive balloon kyphoplasties, the overall cement leakage rate was 31%, with most leakages being anterior and superior [15]. Only 2% were posterior, and most leakages were below 3 mm. Of the distribution of leakages reported from kyphoplasty, 48% were paraspinal, 38% intradiscal, 11% epidural, 1.5% pulmonary, and 1.5% foraminal [16]. Epidural cement leakage has had the worst neurological outcomes [17]. Paraspinal and intradiscal leakages have been less harmful, although some describe intradiscal leakage as one of the most significant predictors of adjacent vertebral fracture [18] (Fig. 41.4).

Fig. 41.4

MRI STIR images showing a fracture line over the L2 vertebral body; post-kyphoplasty portable fluoroscopic image showing escape of the cement through the fractured vertebral end plate into the inferior vertebral disc. Images from personal library

After performing kyphoplasty, the proceduralist must ask the patient about any new symptoms postoperatively. With an epidural cement leak, the patient may experience improvement in back pain but complain of new-onset radicular pain in the lower extremities, in addition to weakness and numbness. Patients may not be able to ambulate and have a positive straight leg raise. There have been reports of epidural cement leakage after pedicle breakage that causes neurological damage after kyphoplasty [2].

Monitoring cement leakages can be difficult, especially since fluoroscopy under a C-arm is the only practical method of imaging during the procedure. Patients are often under deep sedation for the procedure, making intraoperative neurological assessment difficult. Some believe that it is difficult to confirm a cement leak on simple radiogram, and oftentimes a leak can be observed only in a lateral and not anteroposterior view [2]. Furthermore, leakage through the pedicle wall can be difficult to assess, and some report that oblique images would be helpful for prompt detection of leakages after pedicle wall perforation [15]. For these reasons, urgent CT scan post-procedure is recommended if neurological symptoms occur [2]. In a study of 76 vertebrae in 49 patients who underwent vertebroplasty for osteoporotic VCF, more leaks were identified on CT scans than on radiographs by a factor of 1.5 [19].

Cement extravasation into the paravertebral veins may lead to pulmonary embolism or cardiovascular distress [16]. Despite the lower incidence of cement leak in kyphoplasty than in vertebroplasty, there was no correlation between cement embolism to the lungs and the type of procedure performed when post-procedure radiographs in 64 patients were obtained to assess for the presence of pulmonary cement emboli [20]. All patients with pulmonary cement emboli remained asymptomatic. Occasionally, patients have mild dyspnea and rarely experience cardiopulmonary instability making surgical embolectomy necessary.

41.4 Prevention and Treatment

Preventing epidural cement leaks begins with patient selection. Vertebral augmentation should be reserved for patients with intractable, debilitating pain that requires high-dose IV or oral opiates. Similarly, the procedure should be considered in patients for whom conservative management such as physical therapy, oral analgesics, bracing, and epidural steroid injections has failed.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree