182 Epidemic Infections in Bioterrorism

• Anthrax is the agent considered most likely to be used in a bioterrorist attack.

• Suspect a bioterrorism attack when large groups of patients present in a short time period with respiratory or neurologic symptoms, or when an index patient has characteristic findings.

• Use isolation precautions, and give antibiotics based on clinical suspicion, before diagnostic confirmation.

• Always draw blood cultures and send Gram stains in suspicious cases.

• Refer to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) website (www.bt.cdc.gov) for more detailed information on bioterrorism threats, and report any confirmed cases to the CDC.

Perspective*

Biologic agents have the potential to cause as many casualties in a densely populated area as a nuclear weapon. If used in a terrorist attack on civilian populations, biologic weapons could also result in widespread social disruption and complete exhaustion of health care resources.1,5–7

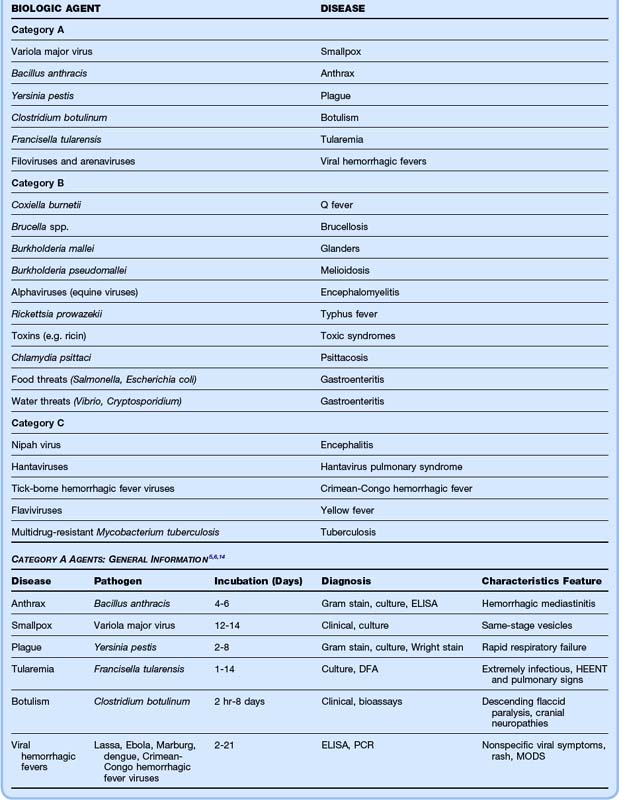

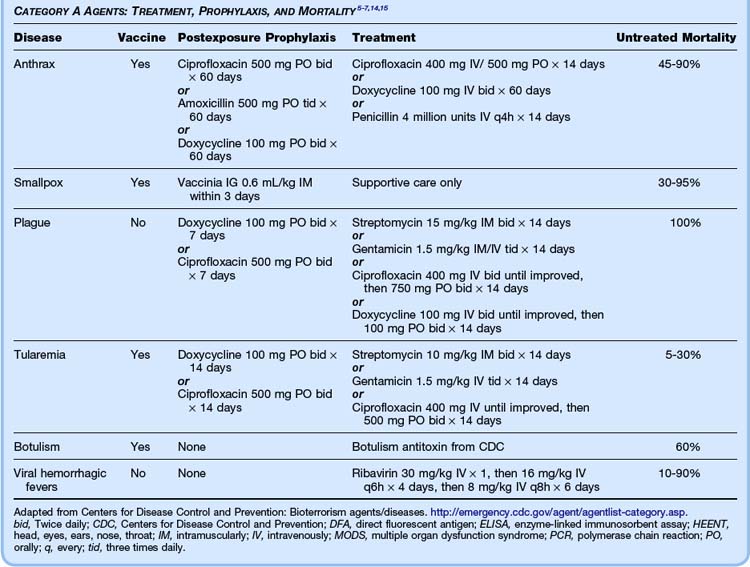

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) classified the major bioterrorist threats into three categories, based on the overall danger to the American public.8 Category A agents are the most easily weaponized and disseminated, cause the highest mortality, produce extensive social disruption, and require special public health preparedness systems. Category B agents do not cause as high mortality as category A agents, but they still result in considerable morbidity and require enhancement of current surveillance systems. Category C agents are the third-highest priority and comprise new and emerging agents that are concerning because of their potential to cause significant morbidity. The list of category A, B, and C agents is given in Table 182.1.

Bioterrorism agents are most dangerous to humans when these agents are in aerosolized form.6 Particles smaller than 10 mcg effectively reach the alveoli. Certain agents (e.g., anthrax, botulinum) are more resistant to environmental degradation than others (e.g., plague). Some agents (e.g., plague, smallpox) may be transmitted from person to person, thus causing high rates of dissemination and requiring strict isolation measures. Until biologic contaminants are excluded, pulmonary isolation measures should be instituted in all these patients. At present, only anthrax and smallpox have vaccines licensed by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, and both vaccines require complex administration schedules.9

Surveillance and management protocols should be instituted at the hospital level for dealing with large numbers of patients who present with respiratory complaints over a short period of time. If surveillance methods do indicate a bioterrorist attack, the community must work to prevent widespread contamination, to help curb the strain on health care resources. A joint report by the CDC and the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services in February 2007 established guidelines to limit the spread of a pandemic infection.10 Measures such as the recommendation that ill individuals stay home from work or school, cancellation of large public gatherings, and the use of strict hygiene techniques in the workplace could help avert a health care crisis.

Anthrax†

![]() Red Flags

Red Flags

Most cases caused by bioterrorism agents manifest initially as nonspecific viral syndromes.

Inhalational anthrax and pneumonic plague are extremely difficult to distinguish clinically and radiographically, and Gram stain may be necessary.

Cutaneous anthrax is often mistaken for a brown recluse spider bite.

Consider smallpox if large numbers of patients who have already had chickenpox present with a diffuse vesicular rash.

Botulism may resemble organophosphate toxicity or a variant of Guillain-Barré syndrome.

![]() Priority Actions

Priority Actions

| Problem | Action |

|---|---|

| Respiratory distress? | Have a low threshold for intubation in these patients. Respiratory failure and hypoxemia can occur rapidly. Always wear a mask while intubating and use rapid-sequence induction to minimize coughing. |

| Septic shock? | Institute early goal-directed therapy with fluids, vasoactive agents, antibiotics, and hemodynamic monitoring. |

| Neuromuscular weakness? | Obtain a vital capacity early in patients with botulism.Diaphragmatic weakness quickly leads to respiratory failure. |

| Potential for spread to health care workers? |