Emergency Department Management of Acute Coronary Syndromes

Charles V. Pollack Jr.

Richard L. Summers

The essential role of the acute care physician is to identify possible ACS patients in a timely fashion, initiate an immediate reperfusion strategy in patients with STEMI, risk-stratify other patients, initiate appropriate therapy and provide for timely specialty consultation as indicated. The challenge to a knowledgeable acute care physician is to individually apply the dearth of group-derived guidelines data to individual patients and orchestrate the necessary comprehensive interdisciplinary care that will largely determine outcome success in ACS.

Management of the ACS patient beyond triage (see also Chapter 3)

Updated AHA/ACC/ACEP guidelines and clinical policies, 2007

Special considerations for reperfusion therapy: primary PCI and patient transfer

A key consideration: systems of care and multidisciplinary cooperation and management

Profile of the ACS Patient

The term “acute coronary syndrome” (ACS) encompasses a spectrum of acute conditions punctuating the chronic atherosclerotic progression of coronary artery disease. These clinical syndromes include unstable angina, ST-segment-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI, formerly termed Q-wave MI), and non–ST-elevation MI (NSTEMI, formerly termed non–Q-wave MI).1 The diversity and variability of presentations within ACS reflect a pathophysiology that inherently is dynamic and progressive in nature. From the moment of plaque disruption (the typical initiating event of ACS), a platelet and coagulation cascade results in restriction of coronary blood flow that may ultimately be partial or complete, stable or dynamic. The essential role of the acute care physician is to identify the ACS patient in a timely fashion, initiate an immediate reperfusion strategy in patients with STEMI, risk-stratify other patients, and initiate appropriate risk-directed therapy and timely specialty consultation as indicated.

Due to the acute nature of the coronary event, the initial risk-stratification process typically takes place in the emergency department (ED) setting. Differentiation of acute coronary syndromes is critical from the emergency medicine perspective, as it relates to the “3 Ts” of emergency coronary care (triage, treatment, and timeliness of specialty consultation).

Initial Triage of the ACS Patient

Triage is the general process of prioritizing patients based on their need for immediate medical treatment and the estimate for benefit from possible interventions. For the ACS patient, triage also initiates empiric therapy and a risk-stratification process, with a primary focus on the STEMI patient because of the extremely time-sensitive nature of reperfusion therapy. The effectiveness of the initial triage is frequently the critical element determining the outcomes for these patients.

Patient Considerations

Patients who opt for emergency care begin their own triage when they consider their symptoms and choose a method of transport to the ED. There are still a significant number of patients who never seek medical attention for a possible coronary event. Many will delay medical attention for varied reasons. The significance of this fact is evident in the poor survival rates reported in those experiencing an out-of-hospital cardiac arrest.2 Over the past few years, national campaigns and public education efforts have brought some improvement in symptom recognition and self-triage experience, but there has been little durable impact, and there are many difficult economic and cultural barriers to be overcome3 (see also Chapter 4).

Emergency Medical Services

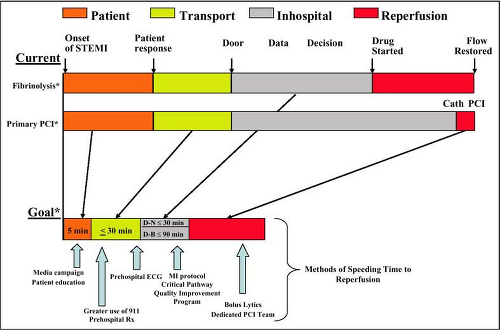

When a patient decides to seek medical attention for a suspected ACS event, emergency medical services (EMS), which include the ambulance and other prehospital services are utilized 25% to 53% of the time.4,5 Although transport is usually a relatively small increment in overall time delay (Fig. 5-1), the responsiveness, assessment, performance of a 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG) (when feasible), and transport by EMS to the destination hospital may be a highly significant component in determining time to treatment.

EMS determination of the initial destination facility of the patient is also an important aspect of EMS triage. Of the approximately 5,000 acute-care hospitals in the United States, 2,200 have cardiac catheterization laboratories and only 1,200 have the capability for percutaneous coronary angiography and intervention.6,7 Some states have developed “cardiac zones,” with well-defined destination protocols, for ambulance services to better assist in the appropriate triage of the ACS patient.8

Emergency Department Triage

The task of ED triage is one of the most difficult responsibilities in health care. Overcrowding and severe limitations in resources often result in extended waiting time during initial triage. This ED triage decision is usually made by an experienced nurse using limited information in a short time frame. Differentiating the ACS patient from one with noncardiac chest pain can be a major initial challenge. Since the timely treatment of the ACS patient is critical in determining outcome, the risk of delays to definitive care is important. To address these issues for the patient with acute chest pain, guidelines have been developed for the identification of ACS patients by ED registration clerks and triage nurses9 (Table 5-1).

STEMI Priority

The STEMI patient has the most time-sensitive ACS condition, requiring reperfusion therapy as early as possible for best outcome.10 Reperfusion therapy has been shown to decrease mortality11 and infarct size,12 and improves regional13 and global left ventricular function.14,15,16 For survivors of MI, the incidence and severity of heart failure is reduced with prompt reperfusion.17,18 Therefore patients must be recognized as early as possible at the time of initial evaluation, whether outside the hospital or in the ED. Current guidelines from the American

College of Cardiology/American Heart Association for reperfusion therapy include a “door-to-needle” time of 30 minutes for fibrinolysis and a “door-to-balloon” time of 90 minutes for primary intervention. It should be realized that these time limits are not goals but the outside limits of timely reperfusion. Reperfusion should be accomplished as early as possible.

College of Cardiology/American Heart Association for reperfusion therapy include a “door-to-needle” time of 30 minutes for fibrinolysis and a “door-to-balloon” time of 90 minutes for primary intervention. It should be realized that these time limits are not goals but the outside limits of timely reperfusion. Reperfusion should be accomplished as early as possible.

Table 5-1 • Guidelines for the Identification of ACS Patients by ED Registration Clerks or Triage Nurses | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Unstable Angina and NSTEMI

Complete risk stratification of ACS patients based upon traditional risk factors, presenting symptoms, and physical findings alone has been shown to be insufficient. Prognosis and selection of treatment strategies for patients with unstable angina (UA)/NSTEMI require further risk stratification.19 However, the 12-lead ECG is central to the triage and diagnosis of ACS and should be obtained rapidly and early in the risk-stratification process. The 12-lead ECG should be obtained within 10 minutes of ED arrival and interpreted by a senior physician knowledgeable in ECG interpretation and ACS triage protocols.20,21 The presence of ST-segment elevation >1 mm in two anatomically contiguous leads consistent with injury has high specificity for STEMI and triggers the institutional reperfusion protocol. Some evidence supports the use of >2 mm in the anteroseptal leads, as this increases the specificity for anterior infarctions (see “Electrocardiography,” below).22 A new or presumably new bundle-branch block obscuring ST-segment analysis may also be indicative of STEMI (see “Electrocardiography,” below).23,24 If ischemic ST-segment depression or dynamic T-wave changes are found on the ECG, the patient may require aggressive anticoagulant (antiplatelet and antithrombotic) therapy.

In summary, triage personnel must maintain high vigilance and a low threshold for consideration of the possibility of ACS. In the absence of an obvious noncardiac cause for chest discomfort, rapid, triage for possible ACS should be initiated. This also requires that the triage nurse be experienced in recognizing patients with atypical symptoms, especially in women, the elderly, and diabetic patients.

Risk Stratification of the ACS Patient

Risk stratification is the process of categorizing patients according to the severity of their illness, potential for an adverse outcome, and the likelihood of incremental benefit from treatment (see also Chapter 1). The CRUSADE Investigators have evaluated mortality risk stratified by patient risk at presentation (low/intermediate/high), and found a convincing association between the number of guideline-recommended therapies used, patient risk, and mortality (Fig. 5-2

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree