5 Emergency Cardiac Ultrasound

Evaluation for Pericardial Effusion and Cardiac Activity

• Emergency cardiac ultrasound is performed by the emergency physician to assess for the presence of cardiac activity, determine whether a pericardial effusion is present, and answer other specific questions.

• Echocardiography can be used during cardiac arrest to guide resuscitation decisions.

• Emergency use of echocardiography is indicated for assessment of cardiac ejection fraction, wall motion abnormalities, and other critical findings that will direct acute diagnostic decision making.

Introduction

Echocardiography has been the “gold standard” for cardiologists for decades. Over the past 20 years, emergency physicians have adopted point-of-care (POC) cardiac ultrasound to answer specific questions on the management of critical patients. Assessment for pericardial effusion and for cardiac activity have traditionally been the principal indications for emergency physicians, but indications for bedside echocardiography are growing rapidly.1

What We Are Looking For

The initial and best evidence-based indications include applications for tamponade, cardiac arrest, and acute heart failure. Rapidly developing areas of cardiac ultrasound include eva-luation of hypotension, pulmonary embolism (PE), acute myocardial infarction, diastolic heart failure, and echocardiographically guided resuscitation (Box 5.1).1,2

Literature Review

Estimation of Global Cardiac Function and Ejection Fraction

Multiple studies have shown the ability of emergency phy-sicians to accurately evaluate cardiac function and ejection fraction.3,4 When compared with cardiologists, emergency physicians were found to have a correlation coefficient of 0.86 with cardiologists when assessing ejection fraction. Cardiologists had a similar coefficient of 0.84 among themselves.

How to Scan/Scanning Protocols

Specific Views

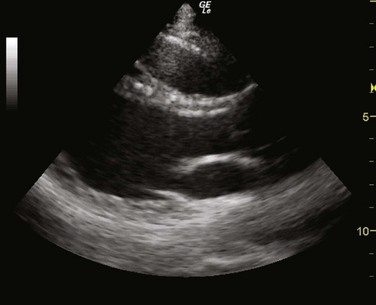

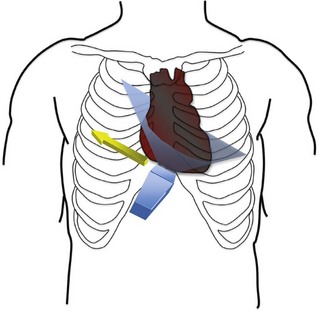

Parasternal Long Axis

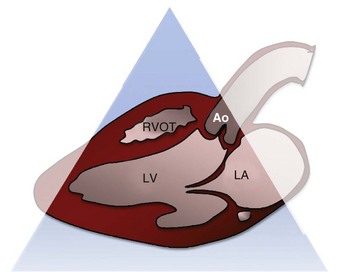

The parasternal long-axis view seen in Figure 5.1 is obtained by placing the probe in the third to fourth intercostal space with the probe marker pointed toward the patient’s right shoulder (Figs. 5.2 and 5.3). The long axis of the heart should be horizontal on the screen with the apex pointed to the left. If the apex is pointed up, the probe is too low and should be moved up an interspace. This view allows visualization of the left ventricle, mitral valve, left atrium, right ventricular outflow tract, aortic valve, and aorta. The descending thoracic aorta is often visualized posterior to the left ventricle in transection.

Fig. 5.2 Parasternal long-axis diagram.

Ao, Aorta; LA, left atrium; LV, left ventricle; RVOT, right ventricular outflow tract.

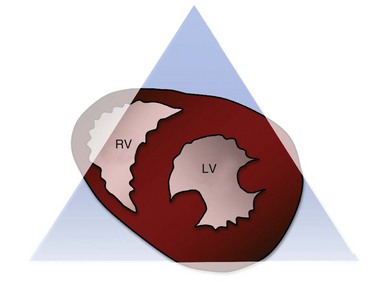

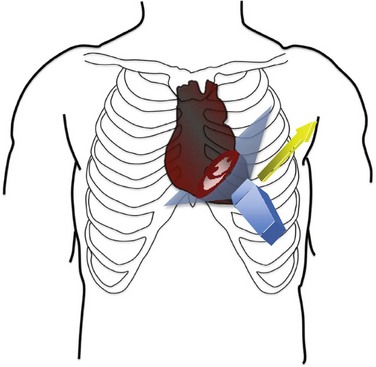

Parasternal Short Axis

The parasternal short-axis view is obtained by rotating the probe 90 degrees from the parasternal long-axis position so that the probe marker is pointed to the patient’s left shoulder (Figs. 5.4 and 5.5). The ultrasound beam is now transecting the heart in its short axis. If the physician tilts the probe so that it is pointing to the base of the heart, the aortic valve is visualized along with the “inflow and outflow” of the right heart. This view includes the right atrium, right ventricular outflow tract, and pulmonic valve. As the probe is tilted more apically, the aortic valve is lost and a cross-sectional view of the mitral valve is obtained (Fig. 5.6). At this point the right ventricle becomes more apparent and takes a position as a crescentic ventricle to the left and superficial to the mitral valve and left ventricle. Finally, as the probe is tilted more toward the apex, the mitral valve is lost and the muscular portion of the left ventricle is visualized. The posterior medial and anterior papillary muscles are visualized at this point, and the circular nature of the left ventricle can be appreciated (Fig. 5.7).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree