27 Ear Emergencies

• Ears are exquisitely sensitive organs. Treating pain is important in caring for patients with ear problems and will facilitate performance of the examination.

• Simple otitis externa can be treated with topical medications and débridement.

• Many cases of uncomplicated otitis media resolve spontaneously. Watchful waiting with use of a “rescue” antibiotic prescription has been shown to decrease unnecessary antibiotic use and improve patient and parent satisfaction.

• Subtle malalignments or malformations after repair of ear trauma can have profound cosmetic consequences.

• Pain from the teeth, pharynx, or temporomandibular joint or from cranial or cervical neuropathies can be referred to the ear.

• Hearing loss must be categorized as conductive or sensorineural. Conductive lesions can often be diagnosed clinically. Sensorineural hearing loss requires urgent referral to an otolaryngologist to improve the chance for recovery of hearing.

Ear Pain

Infections

Otitis Externa

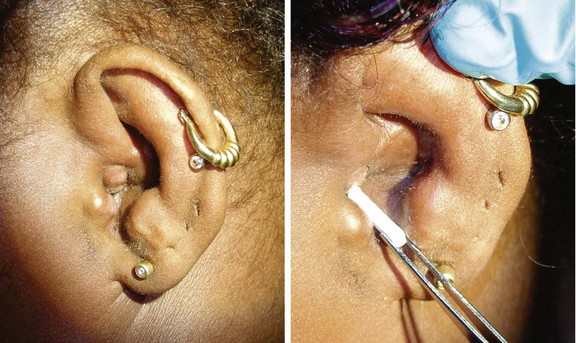

The diagnosis of external otitis is made from the history and findings of pain, pruritus, canal irritation, and edema on physical examination. Thick greenish discharge suggests Pseudomonas, whereas golden crusting implicates S. aureus. Other colored or black discharge may indicate fungal infections, of which Candida and Aspergillus are the most commonly isolated species.1 Small abscesses in the external ear canal can cause obstruction. These abscesses often require incision and drainage, as well as standard treatment of otitis externa.

Treatment

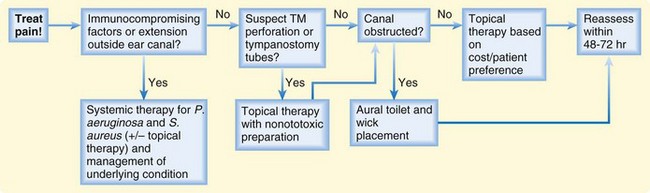

Treatment consists of débridement or aural toilet and antibiotics. Despite a relative lack of controlled studies, the American Academy of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery Foundation has released clinical practice guidelines based on evidence available as of 2005 (Fig. 27.1; also see the Patient Teaching Tips box).2 Briefly, these guidelines are as follows:

1. Distinguish acute external otitis from other causes of otalgia, otorrhea, and inflammation. Diagnostic criteria include rapid onset (2 to 3 days) and a duration of less than 3 weeks. Symptoms include otalgia, itching, or fullness. Signs include tenderness of the pinna or tragus or visual evidence of canal erythema, edema, or otorrhea.

2. Assess for factors that may complicate the disease or treatment (e.g., perforation of the tympanic membrane or eustachian tubes, immunocompromising states, previous radiotherapy). These factors raise the level of treatment needed and heighten suspicion for more invasive disease states such as necrotizing otitis externa (see later). These guidelines pertain to patients older than 2 years with normal states of health.

3. Pay attention to assessment and treatment of pain! Mild to moderate pain usually responds to acetaminophen or a nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug alone or in combination with an opioid.

4. Topical preparations are first-line agents for the treatment of acute uncomplicated otitis externa. Reserve systemic therapy for immunocompromised patients or extension of disease beyond the ear canal. Topical therapy produces drug concentrations 100 to 1000 times that available with systemic administration and can thus overwhelm resistance mechanisms. No clear evidence points to the superiority of one particular treatment. Antiseptic and acidifying agents (e.g., aluminum acetate and boric acid) appear to work as well as antibiotic-containing solutions (e.g., solutions that contain cortisone and Neosporin or a fluoroquinolone). Corticosteroids in the drops decrease the duration of pain by approximately 1 day.3

5. Make sure that the patient can instill the drops correctly. Edema can prevent the drops from entering the canal. Debris or detritus should be removed or irrigated out. Placement of a compressed cellulose or ribbon gauze wick in the canal will enable the drops to penetrate, but placement can be painful. Within 1 to 2 days the canal edema should subside, and the wick falls out or can be removed (Fig. 27.2).

6. If you cannot be sure that the tympanic membrane is intact, use a nonototoxic, pH-balanced preparation such as ofloxacin and ciprofloxacin-dexamethasone.

7. Educate and reassess your patients. Pain should decrease significantly in 1 to 2 days and resolve by 4 to 7 days. Failure to improve may indicate more invasive disease (e.g., necrotizing otitis), inability of drops to reach the canal (wick needed), or noncompliance with therapy.

Fig. 27.1 Algorithm for the treatment of acute otitis externa.

(Adapted from Rosenfeld RM, Brown L, Cannon CR, et al. Clinical practice guideline: acute otitis externa. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2006;134;S4-23.)

![]() Patient Teaching Tips

Patient Teaching Tips

Otitis Externa

Most patients with otitis externa can be managed as outpatients. Follow-up in 1 to 2 days is indicated if a wick is placed for treatment, if oral antibiotic therapy is started, or if the pain does not begin to resolve in 24 to 36 hours.

Patients should discontinue use of the drops after full resolution of their symptoms. Continued use of antibiotics (especially neomycin) can predispose to changes in the environment of the ear canal and foster fungal infections or sensitivity reactions.

Patients must avoid getting water in the ear during the healing process. Cotton balls soaked in petroleum jelly work well as earplugs. Any water that gets into the ear can be removed by gentle blow-drying.

Patients with evidence of significant immunocompromise or failure to improve in 1 to 2 days should be considered for admission to the hospital to be evaluated for more extensive disease.

Drying the ear after swimming or showering helps prevent otitis externa. Placing drops of acetic acid (vinegar) and rubbing alcohol in the ear two or three times a week during periods of heavy water exposure (summer vacation) helps dry the ear and restore the acidic environment that protects against otitis externa.

Otitis Media (Acute and Chronic)

Accumulation of fluid in the middle ear (medial to the tympanic membrane) is termed otitis media. Fluid collections can be clinically sterile, as in barotrauma-mediated effusions or chronic otitis media with effusion, or can result from infectious causes (acute otitis media [AOM]). Infection-mediated effusions may be serous (usually viral in origin) or suppurative (primary or secondary bacterial infection). The common link between all these processes is eustachian tube dysfunction. The eustachian tube acts as a vent and conduit between the middle ear and posterior pharynx in which air pressure between the middle ear and ambient air is equalized and fluid can drain from the middle ear cavity. After infections (primarily upper respiratory infections [URIs]), edema can cause blockage of the tube. Air is easily absorbed through the middle ear tissues, thereby leading to a relative negative pressure in the middle ear. This negative pressure draws fluid into the enclosed cavity. Native or invasive bacteria can work their way into this enclosed area and proliferate.4,5 Common bacterial pathogens are the same as those frequently found in sinus infections and include Streptococcus pneumoniae, nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae, and Moraxella catarrhalis. Currently, approximately 60% to 70% of S. pneumoniae species are covered by the polyvalent pneumococcal vaccine (Pneumovax).6,7

Otitis media is one of the most common reasons for pediatric physician visits, with estimates that $5 billion is spent as direct or indirect costs annually. A significant proportion of cases are probably misdiagnosed, and guidelines have been issued to ensure proper diagnosis and thus curb wasting of resources.8 “Visualization of the tympanic membrane with identification of a middle ear effusion and inflammatory changes is necessary to establish the diagnosis with certainty.”8 Effusions are signified on physical examination by bulging of the tympanic membrane, bubbles or fluid levels behind the membrane, loss of the light reflex (opacification or cloudiness of the membrane), and (most definitively) loss of tympanic membrane mobility on pneumatic insufflation. Newer modalities, such as acoustic reflectometry and tympanometry, also demonstrate middle ear effusions but are not available in many EDs. Tympanic membrane injection (common in crying children) or the presence of fluid alone is not enough to make the diagnosis of AOM. Accompanying fever, pain, purulent drainage, or other systemic signs point to acute infection.

The role of infectious organisms in chronic otitis media is unclear. It was originally thought to be a noninfectious entity, but studies have shown the presence of bacteria (and bacterial DNA, mRNA, and proteins) in a biofilm model of chronic otitis media.9 Current guidelines offer the option of a trial of antibiotics (typically amoxicillin) or watchful waiting as treatment.8