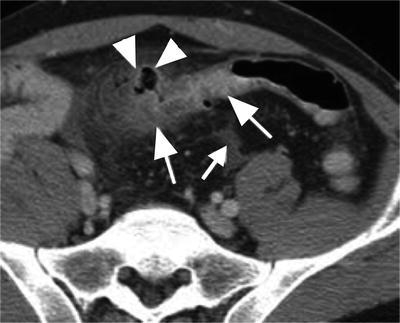

Fig. 26.1

Diverticular disease: (left) diverticulosis, (right) diverticulitis

Diverticulitis refers to inflammation or infection of a diverticulum. The patient with diverticulitis will commonly present with fever, leukocytosis, and left lower quadrant pain; however, the absence of these does not preclude a diagnosis of diverticulitis as about half of patients will not have a fever or leukocytosis [7]. The presence or absence of symptoms can be attributed to the severity of the underlying inflammatory process. Therefore, the diagnosis of diverticulitis is further characterized into uncomplicated and complicated to reflect the severity of the episode. Uncomplicated diverticulitis may be clinically silent with the exception of a mild variance in bowel habits. It accounts for the majority (75%) of cases and is usually amenable to medical therapy. Complicated diverticulitis refers to inflammation of the diverticula in concert with perforation, abscess, obstruction, or fistula. The majority of patients with complicated diverticulitis will require intervention.

Bleeding is the other major complication of diverticular disease. The etiology of a lower gastrointestinal bleed in this setting is secondary to progressive weakening of the vasa recta as the diverticulum forms. The vessels are placed under tension and the protective layers are progressively thinned, ultimately leaving them exposed to injury and rupture [8]. Diverticular disease accounts for approximately 40% of all lower gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding and is self-limiting 90% of the time. Massive bleeding occurs in 5–7% of cases and risk factors are anticoagulation, ischemic heart disease, and the use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Despite accounting for only 10% of diverticula, the right side of the colon is the bleeding source in 50% of cases. Diverticulitis does not increase the risk of diverticular bleeding and inflammation is not classically present during a bleeding episode [9].

Diagnosis

The initial evaluation of a patient with suspected acute diverticulitis includes a history and physical examination, a complete blood count (CBC), urinalysis, and plain abdominal radiographs in selected clinical scenarios. A diagnosis of acute diverticulitis can often be made based on history and physical exam findings, especially in patients with a history of diverticulitis. However, in many cases of abdominal pain, it may be unclear whether diverticulitis is the causative etiology and adjunctive studies may be helpful and warranted. Alternative diagnoses include irritable bowel syndrome, gastroenteritis, bowel obstruction, inflammatory bowel disease, appendicitis, ischemic colitis, colorectal cancer, urinary tract infection, kidney stone, and gynecologic disorders. An elevated white blood cell count often is helpful in confirming the presence of an inflammatory process. Pyuria may reveal a urinary tract infection, and hematuria may suggest a kidney stone. Plain abdominal films may show pneumoperitoneum from a perforated viscus, or signs of bowel obstruction.

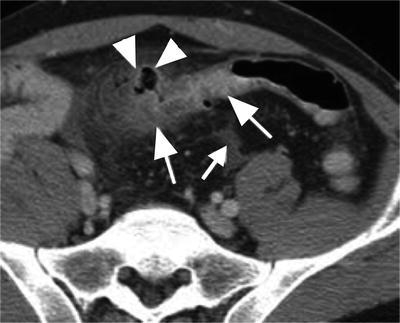

In the modern era, computerized tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen and pelvis is usually the most appropriate imaging modality in the assessment of suspected diverticulitis (Fig. 26.2). Accuracy is enhanced if oral, intravenous, and rectal contrast is used. In this setting, CT is highly sensitive and specific, with a low false-positive rate [10]. Features typical of diverticulitis on CT are: presence of diverticula in descending or sigmoid colon, surrounding fat stranding, and bowel wall thickening. Complications, such as phlegmon, abscess, adjacent organ involvement and fistula, can also be identified and may alter the treatment regimen. A large abscess found on initial CT scan may prompt early percutaneous drainage and delay operative intervention. Severity staging, most commonly utilizing the Hinchey classification system, aids in the selection of patients who are most likely to respond to conservative therapy (Table 26.1) [11]. The severity of diverticulitis at the time of the first CT scan not only predicts an increased risk of failure of medical therapy on index admission but also a high risk of secondary complications after initial nonoperative management [12]. The incidence of a subsequent complication is highest in patients with severe disease on the initial CT scan [13].

Fig. 26.2

CT findings of diverticulitis

Table 26.1

Hinchey classification system

Hinchey stage | |

|---|---|

I | Pericolic abscess |

II | Retroperitoneal or pelvic abscess |

III | Purulent peritonitis |

IV | Fecal peritonitis |

Contrast enema and endoscopy are also occasionally useful in the initial evaluation of a patient with suspected acute diverticulitis. A gently administered single contrast enema may show stenosis/spasm with intact mucosa and associated surrounding diverticulosis. Diverticular strictures may also be apparent as they are usually longer and more regular than in carcinoma [14]. This diagnostic modality has largely been abandoned given the risk of perforation and subsequent complications. Endoscopy has limited use in the acute setting and may exacerbate inflammation or cause perforation [15]. As a follow-up modality, however, endoscopy should be utilized to exclude an oncologic component to the inflammatory disease process. An Australian study conducted by Lau et al. examined the incidence of malignancy after an acute attack of left-sided diverticulitis [16]. Almost 3% of patients received a diagnosis of colorectal cancer, while 26% of patients were diagnosed with polyps >1 cm. The odds of a diagnosis of colorectal cancer were 4 times higher in patients with local perforation, 6.7 times higher in patients with an abscess, and 18 times higher in patients with a fistula when compared to patients with uncomplicated diverticulitis. Once the acute attack has resolved, colonoscopy should be performed to exclude malignancy prior to elective operative intervention.

Management of Diverticular Disease

Uncomplicated Diverticulitis

The treatment of patients with diverticulitis has changed significantly in recent years. Patients may be treated on an outpatient basis in the absence of systemic signs. If they demonstrate mild abdominal tenderness, low-grade fever, and the ability to tolerate oral intake, reliable patients can be treated with oral antibiotics, low residue diet, and close follow-up. Antibiotics should be directed toward typical lower gastrointestinal flora. Oral antibiotic regimens, based on consensus rather than randomized trials, include gram-negative coverage typically with a fluoroquinolone or sulfa-based drug. Anaerobic coverage should be provided with metronidazole or clindamycin. Patients not meeting outpatient criteria will need to be hospitalized for intravenous fluids and antibiotics. Immunocompromized patients will also benefit from inpatient treatment. Intravenous antibiotic regimens such as ampicillin-sulbactam, timentin-clavulanate, or piperacillin/tazobactam are appropriate in this setting. For patients who require intravenous antibiotics but have a demonstrated beta-lactam intolerance, alternative regimens consist of a fluoroquinolone and metronidazole or monotherapy with a carbapenem. Subsequent to successful treatment of acute diverticulitis with conservative therapy, approximately 1/3 of patients will experience another episode. After a second episode, another 1/3 of patients will be subjected to a third attack. Of all patients with diverticulitis, about 1/5 will ultimately require operative intervention [17].

Elective resection can be safely performed 4–6 weeks after the most recent episode has resolved. Guidelines from the American Society of Colorectal Surgeons (ASCRS) taskforce in 2000 recommended segmental resection after two uncomplicated attacks of diverticulitis or after a single episode of complicated diverticulitis. This traditional surgical dictum has been called into question since that time. In a study from the Lahey Clinic, Hall et al. demonstrated that although diverticulitis recurrence was common (36%) following an initial attack that was managed medically, complicated recurrence was uncommon (3.9%) over a follow-up period of 5 years. Right-sided diverticulitis also had a low rate of recurrence [18]. Family history of diverticulitis, length of involved colon >5 cm, and a retroperitoneal abscess were independent risk factors associated with recurrence. In light of these and other data [19] we have become more liberal in our application of expectant management, but still generally endorse the guidelines from the ASCRS while also taking into consideration:

1.

Physiologic reserve

2.

Frequency of attacks

3.

Severity of attacks

4.

Impact on quality of life

Overall, morbidity after open colectomy for diverticulitis ranges from 9 to 54%, while mortality ranges from 0 to 1.2%. Risk factors for morbidity after elective left colectomy for diverticular disease are [20]:

1.

Greater than 10% weight loss

2.

Body mass index (BMI) >30

3.

Left hemicolectomy (versus left segmental colectomy)

Traditionally, patients afflicted with an episode of diverticulitis are initially treated with bowel rest. Once the clinical picture begins to improve they are instructed to consume a clear liquid diet. The diet is then advanced as tolerated. A more aggressive approach limits the concept of bowel rest, with immediate resumption of a low-residue diet instead. Once an acute flare has subsided, a high fiber maintenance diet has been advocated. This may decrease both the formation of diverticula and the chance of a symptomatic recurrence. This recommendation is based on the idea that long-term fiber supplementation produces a bulky stool that results in a larger diameter colon, thereby decreasing segmentation and subsequent pressure, which may be protective in the formation of diverticula. The data in support of this and other dietary measures is not conclusive. Other anecdotal recommendations are to avoid caffeine, alcohol, and tobacco but the data do not indicate that these are risk factors [21]. Additional dietary restrictions frequently given to patients are to avoid seeds, corn, and nuts. While this advice makes intuitive sense, these small difficult to digest particles could become lodged in a diverticulum and predispose a patient to diverticulitis or perforation, a large observational study did not reveal an association with diverticular disease [22].

Complicated Diverticulitis

Small localized and intramural abscesses may resolve without intervention. Larger abscesses (>3 cm) are best managed with percutaneous drainage. After source control has been achieved, clinical improvement should occur within 48 h. In the absence of clinical improvement or if the condition of the patient worsens, repeat imaging may identify a previously undetected abscess, or worsening of an existing abscess, which would prompt a change of therapy. Conservative management of diverticulitis has grown more aggressive, recognizing the benefits of converting an emergency surgical intervention into an elective one. Advances in imaging, critical care, parenteral nutrition, and interventional techniques have lent themselves towards this goal. Mutch et al. examined the efficacy of nonoperative management in acute complicated diverticulitis [23]. Complicated diverticulitis was defined as having an associated abscess or free air diagnosed by CT scan. Out of 136 patients, 28% required percutaneous drainage, and 27% required parenteral nutrition. In total, only 5% (seven patients) failed medical management and required urgent surgery. Forty-eight percent then went on to have elective resections of their diverticular disease. Contraindications to a nonoperative approach include hemodynamic instability, generalized peritonitis, CT scan with significant free air and fluid, or immunosuppression. Operative intervention is also required for clinical deterioration after a period of expectant management.

Operative Approaches

The principles surrounding operative intervention focus on control of sepsis and determination of proper intestinal continuity. Preoperative considerations consist of aggressive intravenous fluid resuscitation and correction of electrolyte abnormalities. Bowel preparation is not indicated in the emergent setting. Historically there have been four basic approaches:

1.

Staged procedure of (a) proximal diversion and drainage, (b) subsequent resection, and (c) final restoration of bowel continuity at a third procedure.

2.

Resection and colostomy (modified Hartmann procedure)

3.

Resection with primary anastomosis and diversion

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree