35 Diverticulitis

• Diverticulitis is an acute inflammatory process caused by injury and bacterial proliferation in an existing diverticulum.

• Patients with diverticular disease may be seen in the emergency department with inflammation manifested as abdominal pain or, less commonly, with hematochezia.

• Consider complicated disease (perforation of a diverticulum or abscess formation) and surgical consultation in patients who have peritoneal findings on examination.

Epidemiology

The prevalence of diverticulosis is related to age and ranges from 5% at 40 years to 65% by 85 years of age. Approximately 70% of patients with diverticula are asymptomatic, whereas the remainder of patients experience at least one major complication. Twenty percent have diverticulitis and 10% have episodes of bleeding from their diverticula.1 Diverticulitis accounts for 6% of emergency department (ED) visits for acute abdominal pain in the elderly and occurs more frequently than appendicitis in this age group.2

Pathophysiology

Diverticulosis

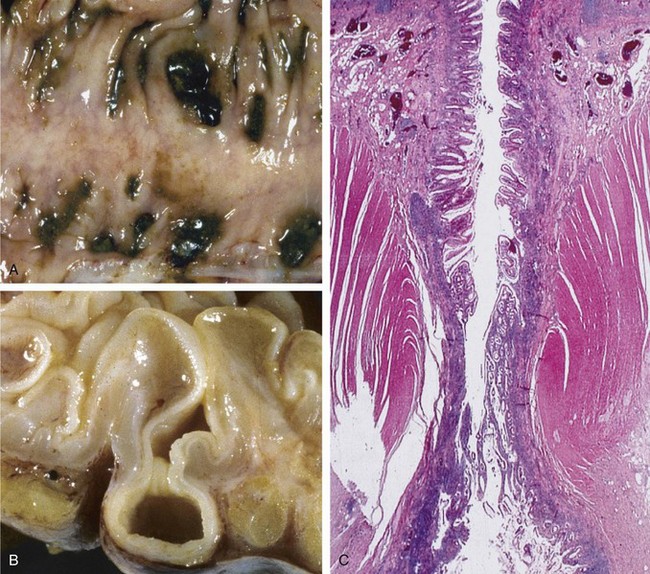

Diverticula are thought to arise from defects in the muscularis layer of the intestines (Fig. 35.1) and are related to abnormalities in muscle tone and increased intraluminal pressure; saclike protrusions eventually form at points of weakness. If stool is caught in these sacs, it becomes inspissated and hardened and causes abrasions of the mucosa that lead to inflammation, although the same end result can occur from pressure differentials alone without the presence of trapped fecal material.

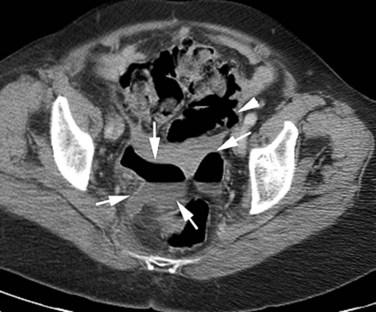

Fig. 35.1 Sigmoid diverticular disease.

(From Kumar V, Abbas AK, Fausto N, Aster J. Robbins and Cotran pathologic basis of disease, professional edition. 8th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2009.)

The left side of the colon is the most common site for diverticulosis in patients with westernized diets and lifestyle. Right-sided diverticula occur more frequently in certain Asian populations. Right-sided diverticula have a higher rate of hemorrhage because of anatomic differences in their development.3 Small bowel diverticula occur most commonly in the duodenum, where they are predominantly asymptomatic. About 20% of small bowel diverticula occur in the jejunum or ileum; complications develop in these diverticula at rates three times greater than in duodenal diverticula.4

Diverticulitis

Diverticulitis arises from the initial microperforation of a diverticulum (Table 35.1).5 The process starts with blockage of the colonic opening of the diverticulum or by direct contact with food and fecal particles lodged in the affected portion of the bowel. Increased intraluminal or direct local pressure causes erosion of the diverticular wall, which leads to inflammatory changes, focal necrosis, and eventually perforation. The process is generally mild and limited by local pericolic fat and mesentery. Virtually all cases of diverticulitis involve perforation of the intestines, with the course of the resultant illness determined by the extent of this perforation. Complicated diverticulitis refers to regional spread of the inflammatory process by the formation of larger abscesses, a fistula with adjacent organs, or peritonitis (Fig. 35.2).1,5 Patients with purulent peritonitis have a mortality rate of 6%, which rises to 35% when fecal soilage of the peritoneal cavity occurs. Patients with diverticular disease occasionally have segmental colitis of the sigmoid colon, probably from fecal stasis or localized ischemia. The effects can be mild or may resemble those of inflammatory bowel disease.1

Table 35.1 Classification of the Severity of Colonic Diverticulitis

| STAGE | DEFINITION |

|---|---|

| 1 | Small, confined pericolic abscesses |

| 2 | Larger purulent collections |

| 3 | Generalized suppurative peritonitis |

| 4 | Fecal peritonitis |

Adapted from Hinchey EG, Schaal PGH, Richards GK. Treatment of perforated diverticular disease of the colon. Adv Surg 1978;12:85-109.