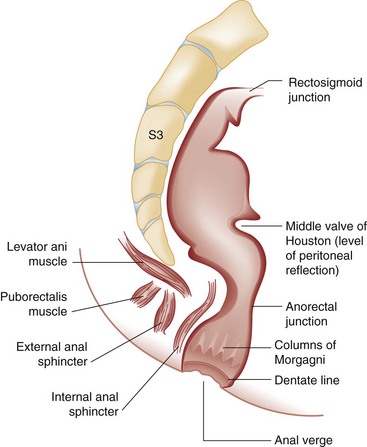

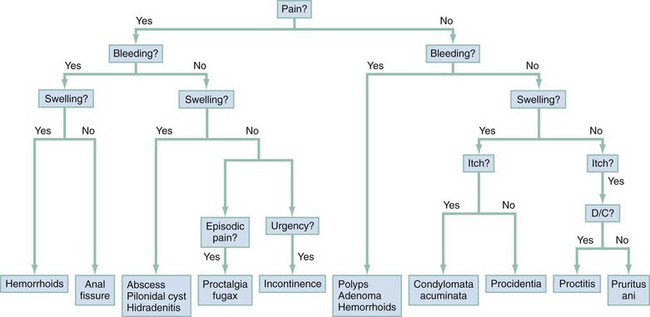

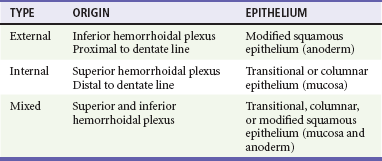

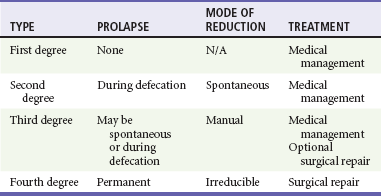

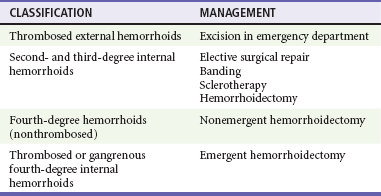

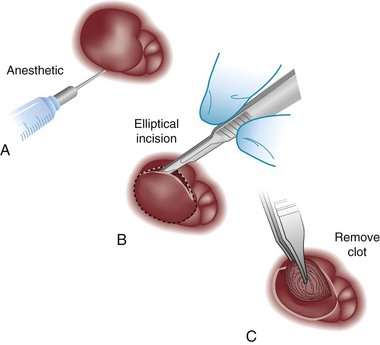

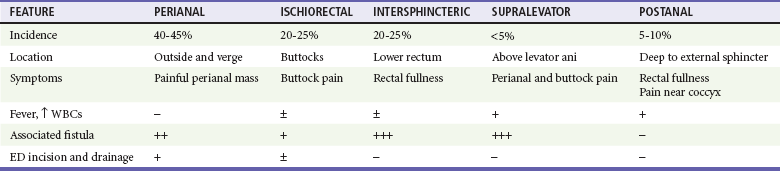

Chapter 96 The anorectum marks the end of the alimentary canal. From its beginning at the rectosigmoid junction at the level of the third sacral vertebra (S3), the rectum follows the sacral curvature for 12 to 15 cm and then sharply turns posteriorly and inferiorly at the puborectalis muscle (Fig. 96-1). Here the anal canal begins its 4-cm course to the anal verge, the orifice whereby stool exits the body. It is supported by three muscle groups, the levator ani and the internal and external anal sphincters. Anal valves are located 2 cm proximal to the anal verge at the dentate line. Above the valves are the anal crypts, which contain mucous glands to provide lubrication during defecation. These constitute a nidus for abscess formation, if occluded. Proximal to the crypts are the columns of Morgagni, where the epithelium of the anal canal changes from pink columnar (as in the rectum) to squamous.1 The superior, middle, and inferior hemorrhoidal arteries provide the blood supply to the anorectum. They arise from the inferior mesenteric, internal iliac, and internal pudendal arteries, respectively. The superior hemorrhoidal veins drain into the portal system, and the inferior hemorrhoidal veins drain into the caval system. Lymphatic drainage is to the inferior mesenteric nodes above the dentate line and to the inguinal nodes from all areas of the anorectum.1 Sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems function together to retain the contents of the rectum until evacuation is desired. Continence is maintained when sympathetic fibers from L1 to L3 (upper rectum) and presacral nerves (lower rectum) inhibit contraction of rectal smooth muscle and L5 fibers cause the internal sphincter to contract. Elimination occurs when parasympathetic fibers from the anterior roots of S2 to S4 cause the rectal wall to contract and the internal sphincter to relax. Voluntary external sphincter control is mediated by motor branches of the pudendal nerve (S2, S3) and the perineal branch of S4. The levator ani is supplied by the pudendal nerve and pelvic branches of S3 to S4 fibers. Sensory perception of rectal distention involves a signal pathway from extramural receptors to parasympathetic fibers from S2 to S4. The abundant sensory nerve endings of the distal anal epithelium perceive sensations that are transmitted by the pudendal nerve.1 Defecation begins as the rectum becomes distended, the internal sphincter relaxes, and stool enters the anal canal. At an appropriate time and place, the external sphincter is relaxed to complete the process of elimination. Sometimes voluntary straining is needed to assist in the passage of stool. When the Valsalva maneuver is performed, the abdominal muscles contract, the rectal angle straightens, and the pelvic floor descends. To postpone defecation, the external sphincter contracts voluntarily. This contraction relaxes the rectal wall and quells the urge to defecate unless there is an underlying sphincter disorder or an overwhelming volume of stool.1 A complete history of anorectal and gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms and the presence of systemic disease elucidate the diagnosis of most anorectal disorders (Box 96-1; Fig. 96-2). Common complaints include bleeding, swelling, pain, itching, and discharge. Standard historical questions about time and circumstances of onset, duration, quality, and exposure to radiation should be asked. Alterations in bowel habits should be noted. These include changes in color, frequency, or consistency of the stool and the presence of straining, flatus, and incontinence of solid or liquid stool. Persons with underlying GI disorders (e.g., Crohn’s disease, cancer, polyps) are predisposed to atypical presentations of anorectal problems. Similarly, those with underlying systemic diseases such as acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), cancer, diabetes mellitus, and coagulopathy are prone to develop more serious complications of standard anorectal conditions. Finally, patients should be asked directly about sexual practices involving the anus.2 The color, amount, and relationship to defecation are important factors in establishing the cause of rectal bleeding. Approximately 10 to 20% of the population experiences rectal bleeding at some time.3 Pain and bright red blood signify anal fissures or hemorrhoids. Fissure pain is sharp, sudden in onset, and not associated with swelling, whereas pain from a prolapsed or thrombosed hemorrhoid is gnawing, continuous, and of more gradual onset. Painless rectal bleeding occurs with internal hemorrhoids, cancer, or precancerous lesions. The relationship of bleeding to defecation is important. Visible blood on the toilet paper usually is caused by anal fissures or external hemorrhoids; however, minute quantities can result from any irritating condition. Bright red blood that drips into the toilet bowl or streaks around the stool is caused by internal hemorrhoids. Blood mixed with stool originates proximal to the rectum, whereas melena indicates a very proximal source. Bloody mucus is associated with cancer, inflammatory bowel disease, and proctitis.3 Patients who report a swelling near the anus or have the sensation of rectal fullness often list hemorrhoids as their chief complaint. Painful swellings that bleed usually are thrombosed hemorrhoids, but other painful lesions such as abscesses, pilonidal disease, and hidradenitis suppurativa must be considered. Painless, itchy swellings may be caused by condylomata acuminata or secondary syphilis. A mass protruding through the anal orifice may signal rectal prolapse. Perianal and rectal carcinoma should be considered in older persons and those with long-standing anorectal complaints.2 When the Philistines defeated the Israelites, the book of I Samuel reports the fate of the avengers: “A deadly panic had seized the whole city, since the hand of God had been very heavy upon it. Those who escaped death were afflicted with hemorrhoids, and the outcry from the city went up to the heavens.”4 In 1815 the battle of Waterloo marked the defeat of Napoleon’s army. Speculation purports that the great leader suffered from hemorrhoids at the time of his defeat.5 Hemorrhoidal disease continues to afflict modern humans, with a 5% incidence in the U.S. population. Both sexes are affected, and an increased frequency has been documented among whites, rural dwellers, and those of high socioeconomic status.6 Hemorrhoids occur when the anal vascular cushions become engorged. Rather than forming a continuous ring around the anal canal, the submucosa forms three distinct cushions of tissue that are richly supplied with small blood vessels and muscle fibers. Blood supply to these cushions is from the superior rectal artery, with some contribution from the middle and inferior hemorrhoidal arteries, which explains why hemorrhoidal bleeding is bright red. The muscularis submucosa cushions the anal canal during defecation to prevent injury and to aid in fecal continence.7 As the supportive tissue deteriorates, often starting in the third decade of life, venous distention, prolapse, bleeding, and thrombosis may occur. Some controversy exists about whether straining and constipation cause these changes by producing venous backflow when intra-abdominal pressure increases.7,8 In pregnant women, direct pressure on a hemorrhoidal vein can produce symptomatic hemorrhoids. Up to one third of pregnant women experience hemorrhoids in the last trimester of pregnancy or the postpartum period. An increased incidence of thrombosed hemorrhoids is associated with traumatic deliveries.9,10 Some familial predisposition is recognized, but whether this is a result of genetics or acquired factors such as diet is unknown. Hemorrhoids are not varicose veins; they are normal structures that manifest symptoms when the muscularis submucosa weakens and the anal cushions are displaced distally.7 Conditions that increase sphincter tone correlate with a higher prevalence of hemorrhoids.8 Portal hypertension does not cause hemorrhoids in adults. The incidence of symptomatic hemorrhoids is similar in patients with and in those without portal hypertension. Rectal bleeding in patients with portal hypertension may be caused by rectal varices, which are vascular communications between the superior and middle hemorrhoidal veins.6,11 A major exception to this observation occurs in the pediatric population; children with portal hypertension are susceptible to hemorrhoidal exacerbations.12,13 Hemorrhoids are classified according to their location and severity (Table 96-1). External hemorrhoids originate below the dentate line and receive their blood supply from the inferior hemorrhoidal plexus. They are covered with modified squamous epithelium (anoderm) and resemble the surrounding skin. Two syndromes are common. First, the veins beneath the skin of the hemorrhoid become dilated and the surrounding subcutaneous tissue becomes engorged, causing swelling or pressure after defecation. Painless, bright red bleeding may occur. Second, the veins can become thrombosed as clots form within them (Fig. 96-3A). This produces acute pain and tenderness to palpation. A bluish discoloration often is noted. Internal hemorrhoids originate above the dentate line and receive their blood supply from the superior hemorrhoidal plexus (Fig. 96-3B). They are covered with a mucosal surface consisting of transitional or columnar epithelium that looks very different from the surrounding anoderm. They are classified according to severity (Table 96-2). Symptoms and signs range from mild, painless bleeding with defecation to irreducible prolapse with unremitting and debilitating pain. First-degree internal hemorrhoids protrude into the lumen of the anal canal, causing a feeling of fullness. Because the mucosal wall lacks sensory nerve endings, these lesions do not cause pain. Second-degree internal hemorrhoids temporarily prolapse outside the anal canal during defecation but spontaneously return to their normal position at the end of the bowel movement. Both first- and second-degree hemorrhoids are amenable to medical management. Third-degree internal hemorrhoids prolapse spontaneously or during defecation and remain outside the body until they are manually replaced into the anal canal. A throbbing, pressure-like pain may accompany bleeding and subsides when the hemorrhoids are reduced. Fourth-degree internal hemorrhoids cannot be reduced and are permanently prolapsed. Continued prolapse leads to the formation of a thrombus with possible progression to gangrene. Definitive treatment for the intense pain and thrombosis is surgical.8,14 The symptoms of nonthrombosed external and nonprolapsing internal hemorrhoids can be ameliorated by the standard regimen—warm water, analgesics, stool softeners, and high-fiber diet (WASH)—aimed at combating the problems that led to the hemorrhoids’ formation (Box 96-2). Anal canal pressures decrease in warm water (40° C). Patients can direct a shower stream at the area for several minutes or take sitz baths. Mild oral analgesic agents reduce the pain. Several over-the-counter preparations are available for the treatment of hemorrhoidal symptoms; however, their use is directed at improved hygiene and temporary symptom relief rather than correction of the condition.15 The use of topical anesthetics, corticosteroids, astringents (e.g., witch hazel), mineral oils, and cocoa butter is controversial. Prolonged use of topical corticosteroids produces atrophic skin changes and is discouraged.7 Stool softeners can make the passage of stool easier, to prevent straining. A high-fiber diet (consumption of 20 to 30 g of dietary fiber per day) produces stool that is passed more easily.16 Patients with second- or third-degree internal hemorrhoids also benefit from this regimen; however, permanent resolution of their symptoms may require surgical intervention (Table 96-3). These patients can be discharged from the ED with the WASH regimen and referred to a surgeon for banding, sclerotherapy, or elective hemorrhoidectomy. Patients with acute, gangrenous, thrombosed fourth-degree internal hemorrhoids should be referred for emergent hemorrhoidectomy. Acutely thrombosed external hemorrhoids can be excised (not incised and drained) in the ED to provide prompt relief within the first 48 hours after the onset of symptoms (Fig. 96-4). Incision results in incomplete evacuation of the clot, subsequent rebleeding, swelling, and the formation of a skin tag.8,17 If not excised, the thrombosed external hemorrhoid resolves spontaneously after several days when it ulcerates and leaks the dark accumulated blood, with relief of associated symptoms. Residual skin tags may persist, making anal hygiene more challenging. In the ED setting, this procedure is not commonly performed in pediatric patients, pregnant women, or immunocompromised patients. Nonsurgical therapy with topical nifedipine (0.3%) and lidocaine (1.5%) gel has been shown to alleviate symptoms when applied twice daily for 2 weeks. The purported effectiveness of this regimen for treatment of thrombosed hemorrhoids is related to the ability of nifedipine to modulate resting sphincter tone and thereby reduce the associated pain and inflammation. However, this regimen is not widely used.18 The development of an anal fissure is the most common cause of intensely painful rectal bleeding of sudden onset. A superficial tear in the anoderm results when a hard piece of feces is forced through the anus, usually in patients who are constipated. Although anyone can experience an anal fissure, it is most common in the 30- to 50-year age bracket.19 It is the most commonly encountered anorectal problem in pediatric patients, especially infants.20,21 Males and females are affected equally. Most fissures occur along the posterior midline, where the skeletal muscle fibers that encircle the anus are weakest. Anterior midline fissures are more common in women than in men. Fissures that occur elsewhere are more likely to be associated with systemic disease such as leukemia, Crohn’s disease, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, tuberculosis (TB), or syphilis.19 Fissures not treated promptly may become chronic, with development of a classical “fissure triad” of deep ulcer, sentinel pile, and enlarged anal papillae (Fig. 96-5). A sentinel pile forms when the skin at the base of the fissure becomes edematous and hypertrophic. A resolving sentinel pile can form a permanent skin tag and may be associated with a fistulous tract. The patient reports sudden, searing pain during defecation that may be accompanied by a small amount of bright red blood in the stool or on the toilet paper. This is followed by a nagging, burning sensation that lasts for a few hours from internal sphincter spasm. Subsequent bowel movements are excruciating, and the external sphincter can exhibit a reflex spasm. Physical examination must be performed cautiously to avoid further spasm and pain. The depth of the fissure, its orientation to the midline, and the presence of a coexisting sentinel pile or edema are noted. Rectal examination during an acute exacerbation often is impossible because of pain and sphincter spasm.19 Specific measures for the treatment of anal fissures are summarized in Box 96-3. Treatment with the WASH regimen (see Box 96-2) focuses on eliminating constipation with a bulking agent, stool softener, and high-fiber diet. Warm sitz baths and limited use of topical anesthetics may be helpful. Parental encouragement of pediatric patients helps prevent encopresis, which can result from a fear of painful bowel movements. Most acute, uncomplicated fissures resolve in 2 to 4 weeks. For adult patients with chronic anal fissures, application of various topical agents aimed at reducing sphincter pressures has been effective.22–24 Hyperbaric oxygen has been used successfully for adjunctive therapy.25 Lidocaine ointment is effective in treating chronic anal fissures. In addition, nitroglycerin ointment applied topically to the anoderm two or three times daily has been shown to relieve the pain from anal fissures. Although it was not associated with more rapid healing, patients receiving this therapy have reported a higher level of comfort during the healing process. The typical side effect of a vasodilatory headache may be experienced by some patients.26 Nifedipine gel (0.2%) in combination with lidocaine (1.5%) applied to the anal area twice daily is effective in promoting healing and reducing discomfort in the management of anal fissures. The mechanism of healing is thought to be the reduction of anal canal pressures by local calcium channel blockade.27,28 When the efficacy of calcium channel blockers was compared directly with that of topical nitrates, the rates of healing and recurrence were similar; however, the incidence of side effects was lower in one study.29 Injection of botulinum toxin by colorectal surgeons (2.5 to 5.0 units of Botox preparation) is effective in relaxing the sphincter tone by inhibiting acetylcholinesterase release but may cause temporary, reversible fecal incontinence.24,27,30–33 Injection into the external (rather than internal) sphincter muscles may reduce this undesirable side effect. It has not yet been studied as a primary treatment in the ED or primary care setting. In comparison with the topical treatments, botulinum toxin may provide some advantages in its rate of permanent healing34; however, the first line of therapy is still dietary modification and the application of topical agents because of their cost, ease of application, and benign side effect profiles.24,33 Long-term treatment of recurrent fissures focuses on reducing resting anal pressures and may require anal dilation performed with the patient under anesthesia or surgical correction to reduce the tone of the internal sphincter.19 Anorectal abscesses and fistulae occur in otherwise healthy adults when the mucus-producing glands at the base of the anal crypts occlude. Abscesses are a manifestation of inflammatory bowel disease, trauma, cancer, radiation injury, and infection (TB, lymphogranuloma venereum, actinomycosis). Common causative bacteria are Staphylococcus aureus, Escherichia coli, Streptococcus, Proteus, and Bacteroides.35 An increased incidence in infants (85% in male babies) has been reported to be associated with congenital abnormalities.36 General Approach.: Anorectal abscess is an acute disease that naturally progresses to fistula formation in the body’s attempt to drain the infection spontaneously. Symptoms vary depending on the site of infection, but incision and drainage constitute the curative treatment in all cases (Table 96-4). Delay of medical management may allow extension of the infection and eventual compromise of the sphincter mechanism.37 Adjunctive antimicrobial therapy is indicated in patients who are immunocompromised or diabetic or have valvular heart disease. Tetanus immunization status should be verified. The sites of anorectal abscess formation are depicted in Figure 96-6. The difficulty in diagnosis is that pain often precedes physical findings of a mass or fluctuance. Approximately 34% of patients with AIDS develop anorectal abscesses and fistulae, which may include opportunistic organisms in addition to the usual ones. HIV-infected patients appear to be more likely than their seronegative cohorts to have an incomplete fistulous tract. This condition prevents adequate spontaneous drainage, highlighting the urgency of treating these patients promptly. A small incision is desirable, when possible, because wound healing in general may be impaired.

Disorders of the Anorectum

Principles of Disease

Clinical Features

Rectal Bleeding

Swelling and Masses

Specific Anorectal Problems

Perspective

Principles of Disease

Clinical Features

Management

Anal Fissures

Clinical Features

Management

Abscesses and Fistulae

Management

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Disorders of the Anorectum

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue