32 Diseases of the Stomach

• Dyspepsia, gastritis, peptic ulcer disease, and gastric carcinoma represent a progressive spectrum of illness.

• Helicobacter pylori is the causative agent of 90% of duodenal ulcers and 60% of gastric ulcers; it is a precursor to gastric carcinoma and is the only bacterium listed as a class I carcinogen.

• In the absence of H. pylori, use of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs is the cause of peptic ulcer disease in up to 60% of patients.

• The findings associated with acute dyspepsia and acute coronary syndrome are often indistinguishable in the emergency department. The primary diagnostic goal of the emergency physician is to exclude acute coronary syndrome through risk stratification and appropriate testing.

• In a hemodynamically stable patient with peptic ulcer disease without perforation, first-line treatment consists of a 6-week trial of a proton pump inhibitor.

• Serologic testing for H. pylori is more cost-effective than empiric treatment without testing.

• All emergency department patients with dyspepsia require referral for outpatient evaluation for serologic testing or endoscopy (or both) to exclude malignant disease.

Epidemiology

Dyspepsia refers to chronic or recurrent pain of gastroduodenal origin centered in the upper part of the abdomen. Dyspepsia affects 25% to 40% of people in industrialized nations, who regularly experience pain accompanied by any or all of the following associated symptoms: bloating, fullness, early satiety, nausea, anorexia, heartburn, regurgitation, and belching.1 Patients experiencing dyspepsia with endoscopic evidence of gastric mucosal inflammation are said to have gastritis, and those with ulcerations of the stomach or duodenal lining have peptic ulcer disease (PUD). Dyspepsia, gastritis, PUD, and the long-term complication gastric carcinoma represent a progressive spectrum of illness.

Dyspepsia accounts for 2% to 5% of annual visits to primary care physicians in the United States, and more than 1 billion health care dollars is spent on prescription medications for this disorder each year.1 PUD chronically affects large portions of the U.S. population and leads to impressive health expenditures because many affected patients leave the workforce. More than 7000 American deaths are attributed to PUD each year, largely as a result of perforation and gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding.

In up to 60% of patients in whom dyspepsia is diagnosed, the results of endoscopic evaluation are nondiagnostic.1 The remaining 40% generally have one of three causative diagnoses: PUD, gastroesophageal reflux disease, or gastric cancer.2 The broad differential diagnosis of recognized causes of PUD is summarized in Table 32.1.

Table 32.1 Differential Diagnosis of Peptic Ulcer Disease

| Cardiovascular | |

| Gastrointestinal | |

| Esophageal | |

| Stomach | |

| Other | |

From Ferri FF. Ferri’s clinical advisor 2007: instant diagnosis and treatment. St. Louis: Mosby; 2006.

Duodenal ulcers occur three to four times more frequently than gastric ulcers worldwide, with men being affected more commonly than women for both ulcer types. The male-to-female ratio for duodenal ulcer (4 : 1) is higher than that for gastric ulcer (2 : 1). Such distributions are observed mainly in the developing countries of Africa and Asia. In westernized societies, the distribution of both ulcer types between the sexes has become more equal over the past few decades, although the mechanisms underlying these epidemiologic changes are unknown.3

PUD is the most common cause of upper GI bleeding in the United States and accounts for 27% to 40% of all cases.4 Patients with PUD who are at highest risk for upper GI bleeding include alcoholics, chronic users of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and patients with renal dysfunction.

Pathophysiology

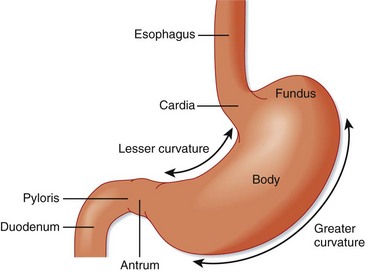

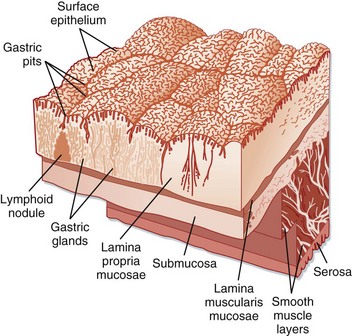

The stomach is anatomically subdivided into three parts: the fundus, the corpus (body), and the antrum (Fig. 32.1).5 This subdivision reflects differences in function. The stomach functions as a reservoir for ingested meals, as well as the site of food agitation with gastric secretions—the first step in digestion (see Fig. 32.1). The acidic fluid is secreted by parietal cells in the fundus and body of the stomach under the control of hormones secreted by endocrine cells in the antrum. Acid secretion is controlled by the complex interaction of gastrin from G cells and histamine from enterochromaffin-like cells. Somatostatin further regulates these cells by inhibition (Fig. 32.2).

Fig. 32.1 Divisions of the stomach.

(From Zuidema G. Shackelford’s surgery of the alimentary tract. 4th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1995.)

Fig. 32.2 Surface of the gastric mucosa.

(From Zuidema G. Shackelford’s surgery of the alimentary tract. 4th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1995.)

PUD results from a complex interplay of factors that disrupt the delicate balance between the production of protective barrier agents, such as bicarbonate-rich mucus, and the hypersecretion of acid from parietal cells. Recognition of Helicobacter pylori as the causative agent of 90% of duodenal ulcers and 60% of gastric ulcers has led to a paradigm shift in the understanding and management of PUD.6

Infectious Causes

H. pylori, a gram-negative, helix-shaped bacterium, infects at least 50% of the population worldwide and is recognized as an important risk factor for the development of PUD and ultimately gastric adenocarcinoma and lymphoma. Infection is probably acquired in childhood and, in the absence of antimicrobial therapy, persists for life with an estimated lifetime risk for PUD of 15%.7–9 Risk factors for the acquisition of H. pylori include sharing of a bed in childhood, large number of siblings, lower socioeconomic status, and lack of a fixed hot water supply.6,19 Although it is still unclear whether transmission occurs person to person, three different mechanisms for such transmission have been postulated: fecal-oral, through saliva, and by vomitus.6,9

H. pylori causes acute dyspepsia characterized by epigastric pain, nausea, vomiting, and halitosis. Symptoms usually last several weeks and then disappear, although the organism loiters within the stomach. Gastritis persists throughout life in various locations; it shifts from an antrum-predominant pattern to a corpus-predominant pattern or pangastritis.10 The chronic phase of the disease is usually benign, but in susceptible individuals, complications such as gastric or duodenal ulcers may arise.

If sufficiently virulent, H. pylori gastritis leads to destruction of the gastric mucosa, which can ultimately result in the development of intestinal metaplasia or eventually carcinoma. The rate of gastric acid secretion declines, thereby fostering conditions beneficial to colonization of the gastric lumen by fecal organisms. H. pylori eventually disappears because the organism is ill-equipped to compete with a growing number of other organisms and is unable to thrive on metaplastic cells in the absence of hyperacidic conditions. Despite its eventual demise, the initial invasion of the stomach lumen by H. pylori incites conditions that favor the evolution of non-cardia–associated gastric cancer.6

Though most common, H. pylori is not the sole infectious cause of PUD. Helicobacter heilmannii, another spiral nonspirochetal bacterium transmitted via domestic animals and monkeys, has been associated with H. pylori–negative duodenal ulcers. It is much rarer than H. pylori, is less pathogenic, and can easily be differentiated by routine histology. Treatment strategies similar to those for H. pylori are successful in eradicating this organism.10

Additional infectious agents include cytomegalovirus (CMV), herpes simplex virus type 1, (HSV-1) and syphilis. CMV was first associated with peptic ulcers in renal transplant recipients and is the only organism to be significantly associated with peptic ulceration in persons positive for human immunodeficiency virus. The ulcers in these patients are usually gastric and numerous. The diagnosis is confirmed by the finding of intranuclear inclusion bodies or CMV DNA (or both) in the gastric mucosa on biopsy specimens taken from the base of the ulcer. HSV-1–induced ulcers are generally located in the antrum and often occur in immunocompetent individuals.10

Drug-Related Causes

In the absence of H. pylori, use of NSAIDs is the cause of PUD in up to 60% of patients.10 Because gastroduodenal damage does not occur in all patients taking NSAIDs, it is important to identify those at increased risk (Box 32.1). Factors associated with higher rates of NSAID-related GI complications are a previous history of PUD or hemorrhage, age older than 65 years, prolonged use of high-dose NSAIDs, use of more than one NSAID, concomitant use of corticosteroids or anticoagulants, and serious comorbid illness such as cardiovascular, renal, or hepatic impairment, diabetes, or hypertension.11 Many other drugs are associated with PUD and are listed in Box 32.2.

Box 32.1

Nonsteroidal Antiinflammatory Drug–Induced Risk Factors for Peptic Ulcer Disease

History of complications of peptic ulcer disease

Concurrent use of other anticoagulants

High dose of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs or prolonged use

Significant comorbid diseases (coronary artery disease, chronic kidney disease)

From Dincer D, Duman A, Dikici H, et al. NSAID-related upper gastrointestinal bleeding: are risk factors considered during prophylaxis? Int J Clin Pract 2006;60:546-8.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree