Difficult and Failed Airway Management in EMS

Jan L. Eichel

Mary Beth Skarote

Michael F. Murphy

THE CLINICAL CHALLENGE

The prehospital environment presents an array of unique circumstances to the airway practitioner: The scene is often chaotic and may pose hazards to the emergency medical services (EMS) personnel (e.g., flood, fire, radiation, electrical wires, toxic environment, etc.). In addition, access to the patient and the airway may be challenging because of a variety of factors related to extrication and patient or paramedic position. Even with the patient on a stretcher in an ambulance or helicopter, positioning for airway management may be difficult. In fact, some would argue that all airway management in the field is difficult, particularly if more than basic maneuvers are to be used.

Environmental conditions faced by EMS providers are uncontrollable: both the darkness of night and bright sunlight of day present unique difficulties. Dark environments may hinder the preintubation airway assessment and obscure nonverbal communications among personnel that are inherent in complex rescue environments. Alternatively, bright sunlight is likely to interfere with laryngoscopic visualization of the larynx. Weather conditions, scenes of violence, tactical rescue, large crowds, equipment limitations, well-meaning bystanders, lack of knowledgeable assistants, and other factors conspire to enhance the degree of difficulty posed to the EMS airway manager.

Identifying a difficult airway and managing a failed airway are both technical skills that are no different in the out-of-hospital environment than they are in-hospital. Thus, the cognitive and technical skills required of prehospital practitioners are comparable to those practicing in emergency departments (EDs), operating rooms (ORs) and other in-hospital venues, differences in available equipment and backup not-with-standing.

FACTORS SPECIFIC TO THE OUT-OF-HOSPITAL DIFFICULT AIRWAY

There are two interrelated considerations governing management of the difficult airway in the prehospital environment: time factors and anatomical factors.

Time Factors

When is it better to wait?

Although all emergency airway management situations share this feature, identification of a difficult airway might influence the provider either to be more or less likely to intubate the patient before transport. Consider, for example, the following two cases, each with an anticipated 10-minute transport time:

A 40-year-old, 80-kg man with sudden collapse, Glasgow Coma Scale 6, with no swallowing reflex, normal respiratory pattern with O2 saturations of 99%, and severe ankylosing spondylitis.

A 40-year-old, 80-kg man extricated from a house fire, with stridor, O2 saturations of 70%, and evidence of upper airway burns.

Both patients have clear indications for securing the airway, although the decision making, particularly with respect to urgency, should be quite different.

In the first case, if the patient is not deteriorating further, it often is best to defer intubation to the ED, where a more formal and controlled neuroprotective RSI can be performed and there are additional options, such as flexible endoscopy, for this difficult airway. The patient’s respiratory status, and his or her oxygen saturation, are adequate. Training must emphasize that preservation of vital functions equates to gas exchange, and does not necessarily equate to endotracheal intubation. Additionally, the patient has a chronic difficult airway, one that will not become increasingly difficult if intubation is delayed. The provider and system medical directors must be wary of the technical imperative—that operators generally will perform an authorized procedure more often

than it is required or indicated. In fact, there is growing evidence that in certain situations, prehospital intubation may not improve outcomes, and may even lead to worse outcomes, and may even lead to worse outcomes.

than it is required or indicated. In fact, there is growing evidence that in certain situations, prehospital intubation may not improve outcomes, and may even lead to worse outcomes, and may even lead to worse outcomes.

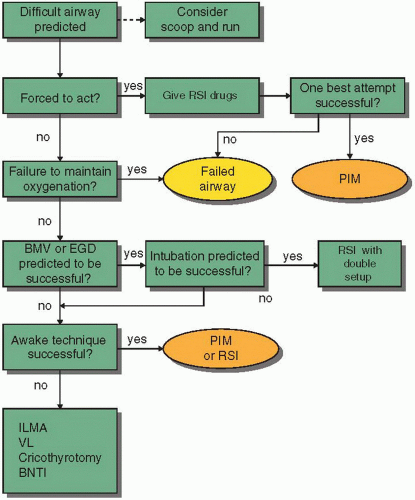

In the second case, the operator is forced to actively manage the airway despite predicted difficulty with laryngoscopy. Even a brief delay, such as a 10-minute transport, allows time for further deterioration, increasing the threat to the patient and making intubation progressively more difficult. The decision to intubate here is clear, and the provider must proceed deliberately down the EMS Difficult Airway Algorithm (Fig. 30-1).

Anatomic Factors

Predicting the difficult airway

The preintubation airway assessment is essential to identify patients likely to present difficulties for laryngoscopy, bag-mask-ventilation (BMV), extraglottic device (EGD) placement, or cricothyrotomy based on a focused examination of external anatomic features (see Chapter 2). This evaluation permits one to make appropriate airway management plans (Plans A, B, and C) that are most likely to be successful.

The patient with acceptable oxygen saturations and a short transport time displaying predictors of difficult laryngoscopy might be better served by a timely transport to the nearest ED, where

there are more resources and skilled personnel. This is particularly the case when the difficult airway is chronic or stable, and is not the reason the patient requires intubation. For example, consider the 40-year-old patient above, who had experienced sudden collapse. Suppose that the anticipated transport time is not 10 minutes, but 20 minutes. Suppose also that preintubation assessment identifies that the patient has had head and neck surgery and radiation for cancer, and has limited mouth opening, neck scarring, and some distortion of anatomy. The difficult airway here is stable and will not worsen during transport to an ED, thus making even more compelling the decision to defer intubation until after ED arrival. This extends the window of time that is “acceptable” for transport without intubation because the risk/benefit ratio argues in favor of taking the patient, unintubated, to the ED. This is in stark contrast to the second patient described above with upper airway burns and stridor. Consider this patient in the context of a 5-minute transport time. Here, regardless of how short the transport time is, the likelihood of imminent deterioration both compels intubation and argues for undertaking this at the earliest opportunity. Thus, both the nature and the “stability” of the difficult airway become key factors in the “intubate versus transport” decision. This has been identified as ‘context sensitive’ airway management.

there are more resources and skilled personnel. This is particularly the case when the difficult airway is chronic or stable, and is not the reason the patient requires intubation. For example, consider the 40-year-old patient above, who had experienced sudden collapse. Suppose that the anticipated transport time is not 10 minutes, but 20 minutes. Suppose also that preintubation assessment identifies that the patient has had head and neck surgery and radiation for cancer, and has limited mouth opening, neck scarring, and some distortion of anatomy. The difficult airway here is stable and will not worsen during transport to an ED, thus making even more compelling the decision to defer intubation until after ED arrival. This extends the window of time that is “acceptable” for transport without intubation because the risk/benefit ratio argues in favor of taking the patient, unintubated, to the ED. This is in stark contrast to the second patient described above with upper airway burns and stridor. Consider this patient in the context of a 5-minute transport time. Here, regardless of how short the transport time is, the likelihood of imminent deterioration both compels intubation and argues for undertaking this at the earliest opportunity. Thus, both the nature and the “stability” of the difficult airway become key factors in the “intubate versus transport” decision. This has been identified as ‘context sensitive’ airway management.

Figure 30-1 • The EMS Difficult Airway Algorithm. See discussion of the Difficult Airway Algorithm in Chapter 3 for explanation. RSI, rapid sequence intubation or other medication-assisted intubation technique; PIM, post-intubation management; EGD, extra-glottic device; ILMA, intubating laryngeal mask airway; VL, video laryngoscopy; BNTI, blind nasal tracheal intubation. |

APPLYING THE EMS DIFFICULT AIRWAY ALGORITHM

When intubation of a difficult airway is required, the EMS Difficult Airway Algorithm (Fig. 30-1) directs one to weigh carefully the RSI (or other medication-assisted intubation) versus “awake” intubation decision. The thought process is identical to that described in Chapter 3. At any point after initiation, if the chosen method is unsuccessful, and oxygenation cannot be maintained, one should move promptly to the failed airway algorithm (Chapter 3). In situations where difficulty is predicted, and airway management is urgently indicated, securing help using on-scene personnel is advisable.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree