CHAPTER 43 DIAPHRAGMATIC INJURY

ANATOMY AND PHYSIOLOGY

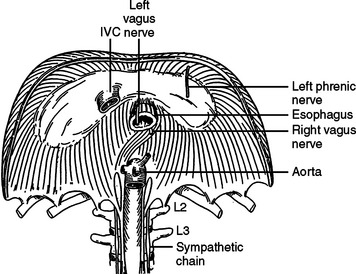

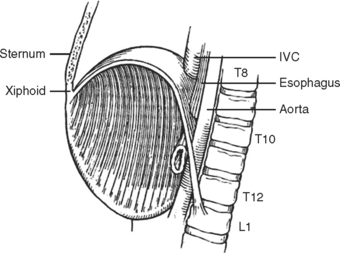

The diaphragm is a musculotendinous organ that separates the thoracic cavity from the abdominal cavity.1,2 This important organ arises from the confluence of the abdominal peritoneum and the parietal pleural during the first trimester of pregnancy. The muscular ingrowth represents an extension from the circumference of the thoracic inlet, specifically the posterior sternal border, the inner surfaces of the lower six costal cartilages, and the posterior lumbocostal arches. These three muscular groups join together as a central tendon, which has three leaflets, namely, left, right, and central leaflets (Figures 1 and 2). The most medial posterior margins are formed by the crura. The central leaflet is located posterior to the sternum and inferior to the heart; it contributes to the pericardial fibers. The right and left leaflets are located posterolaterally in each hemithorax. Incomplete closure of this posterior lateral leaflet results in herniation in the posterior lateral foramen of Bochdalek. Partial closure may result in pleural and peritoneal apposition without union as a central tendon.3 This results in an eventration that may be an important consideration in the differential diagnosis of blunt diaphragmatic injury (Figures 3 and 4).3

The diaphragm, as a muscular organ, varies widely in contour during the ventilatory cycle.1 During full expiration, the diaphragmatic dome extends high into the thoracic cavity. When the diaphragm contracts during forced inspiration, the central tendon is pulled inferiorly and becomes more plate-like.1 This reduces the intrathoracic pressure and raises the intra-abdominal pressure. The excursion of the diaphragm during forced expiration is great; the dome of the diaphragm elevates to the level of the fourth intercostal space at the sternal junction on the right side and to about the level of the fifth intercostal space on the left side.1,2 The diaphragm may extend inferiorly at least three intercostal spaces during full inspiration. The most inferior extension posteriorly occurs at the crura. The right crus arises from the bodies and fibrocartilages of the lumbar vertebrae one through three, whereas the smaller left crus arises from the first and second lumbar vertebrae. They join superiorly to encompass the esophagus at the esophageal foramen. The posterior lateral sulcus or recess of the diaphragm is directly posterior to many of the intra-abdominal organs. Consequently, the posterior sulcus extends inferiorly to the midportion of the kidneys. This inferior extension is often not appreciated when patients with upper abdominal gunshot wounds or stab wounds are treated for intra-abdominal injuries; thus, perforation of the diaphragm in this area is easily overlooked. The resultant hemothorax is diagnosed postoperatively. Careful inspection followed by repair and tube thoracostomy precludes the development of this complication.

The diaphragm has three major foramina (see Figure 1). The aortic hiatus is the most posterior, located between the diaphragmatic muscle and the 12th vertebra. The esophageal hiatus is bordered by the strong muscular crura; the left crus encircles the esophagus and forms an important part of the lower esophageal sphincter. Immediately posterior to the esophagus, sinuous fibers from each hemidiaphragm join as the median arcuate ligament, which is anterior to the aorta and superior to the celiac axis. Immediately posterior to the esophageal foramen on the right side is the foramen for the inferior vena cava (see Figure 1). There are also lesser diaphragmatic apertures. The anterior foramen of Morgagni is in the retroxiphoid space; the internal mammary arteries pass through this foramen while coursing from the mediastinum before dividing into the superior epigastric arteries and the subcostal arteries.4 The accompanying veins follow the same course.

The median plane of the diaphragm extending from the foramen of Morgagni to the esophageal foramen, the so-called median raphe, is less vascular than the more lateral muscular portions of the diaphragm (see Figure 2). This plane can be divided to provide better exposure to the inferior mediastinum. Care must be taken, however, to prevent injury to the phrenic vein, which may cross this median plane about 1 cm above the esophageal hiatus. This vein, if not controlled while dividing the median raphe between the foramen of Morgagni and esophageal hiatus, can lead to major hemorrhage.

The diaphragm is innervated by the phrenic nerve with arises from the cervical portion of the spinal cord, namely, C3, C4, and C5 (see Figure 1).1 After these nerves pass inferior through the mediastinum to the medial portion of the diaphragm, they curve laterally, like a fan, from the central medial portion of the diaphragm to the anterior, lateral, and posterior attachments (see Figure 1). In theory, one should protect these nerves while performing surgery on the diaphragm; this is accomplished by detachment of the diaphragm from the peripheral thorax. This is seldom necessary for most patients with diaphragmatic injury. When the origins of the diaphragm are to be relocated for treatment of unusual injuries, however, care should be taken to protect the neural innovation as much as is practical.

INCIDENCE OF DIAPHRAGMATIC INJURIES

The reported incidence of diaphragmatic injury varies widely. Asensio et al.,2 in a multicenter review, identified a 3% incidence of diaphragmatic injuries for all patients sustaining torso trauma with a range of 0.8%–5.8%; this wide range reflects the different types of injuries treated at each institution and the diligence one places on confirming a diaphragmatic perforation. Rural trauma centers are more likely to treat patients with blunt diaphragmatic injury, whereas penetrating diaphragmatic injury predominates in patients presenting to inner city trauma centers.5

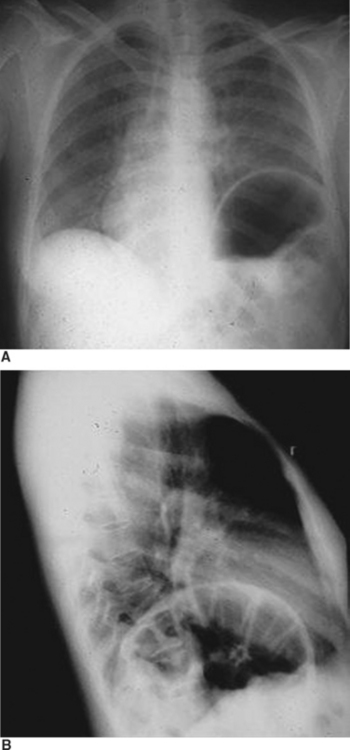

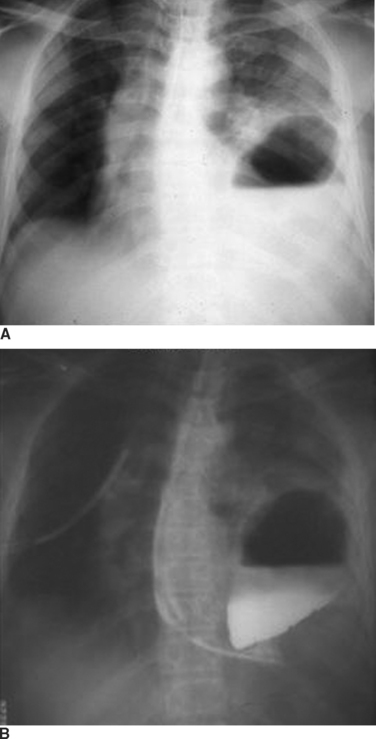

The reported incidence of diaphragmatic rupture may also reflect the different therapeutic approaches to patients with both blunt and penetrating abdominal wounds.6 Most patients with penetrating stab wounds to the abdomen are now being treated nonoperatively when the patient exhibits no signs of peritonitis or hemoperitoneum.7,8 This is also true for patients with lower thoracic stab wounds causing hemopneumothorax which, based on prior experiences with a more liberal approach to exploratory laparotomy, would be associated with a high incidence of confirmed diaphragmatic penetration.8 This includes some patients who have hemothorax treated by tube thoracostomy; many of these patients have unrecognized diaphragmatic perforation (Figure 5). Moreover, patients with through-and-through anterior to posterior right upper quadrant gunshot wounds near the liver and associated right-sided hemopneumothorax are being treated by tube thoracostomy alone, even though there are at least two diaphragmatic perforations. The missile in this setting would pass through the lower rib cage anteriorly, enter the anterior hemithorax, pass through the anterior portion of the diaphragm, transit the liver, re-enter the chest through the posterior portion of the diaphragm, and exit through the posterior chest wall.9 When treated only with right tube thoracostomy for hemothorax, the diaphragmatic perforations are not diagnosed, and therefore, not coded in the trauma registry.8 When diagnostic peritoneal lavage (DPL) was performed routinely for patients with penetrating wounds of the lower rib cage, the effluent would be pink with a red cell count less 100,000/cm3 in patients with isolated diaphragmatic perforation.8 Laparotomy in these patients would confirm a diaphragmatic perforation that was sutured.10 The current trend for routine ultrasonography (US) in patients with abdominal injury has replaced DPL; US is less sensitive for identifying small amounts of blood. Consequently, clinically insignificant diaphragmatic perforations are not being recognized and are not coded in the trauma registry. Penetrating diaphragmatic perforation after upper abdominal wounds may also go unrecognized despite laparotomy for repair of other intra-abdominal visceral injuries. The perforation may be missed because the missile is thought to have penetrated only the transversalis abdominus muscle. When a subsequent hemothorax appears postoperatively, the treating physician, hopefully, will recognize that there was a missed diaphragmatic injury. Patients with blunt injury are less likely to have a diaphragmatic injury that is not recognized during the same hospitalization (Figure 6). There are, however, a number of patients who present with a diaphragmatic hernia years after major blunt torso trauma when diaphragmatic injury was not recognized initially.

During the 1970s, when routine laparotomy was performed for all penetrating abdominal wounds and careful examination of the inferior diaphragmatic extensions was routine, the incidence of diaphragmatic perforation was approximately 19% for upper abdominal gunshot wounds and 11% for upper abdominal stab wounds.8 Now that laparotomy for penetrating abdominal wounds is performed more selectively, the incidence of confirmed diaphragmatic perforation is about 8% for gunshot wounds and 2% for stab wounds. In contrast, the recent incidence of diaphragmatic injury in patients admitted after blunt torso injury is less than 1%; most patients with blunt rupture of the liver or spleen are treated nonoperatively. Patients requiring laparotomy for blunt abdominal injury have about a 3% incidence of diaphragmatic rupture.5,8

MECHANISM AND LOCATION OF INJURY

The location of diaphragmatic perforation varies with mechanism of injury.2,8 The classic scenario for blunt diaphragmatic injury is a head-on motor vehicle collision or a T-bone impact causing a marked increase in the intra-abdominal pressure, thereby stretching the diaphragm to the point of rupture. The rupture typically occurs in the posterior lateral segment in the central tendon of the left diaphragm, often with extension into the muscular portion of the diaphragm. Blunt rupture can also occur after assaults, stompings, falls from a height, and explosions.11 Although the posterior lateral location is the most common site for injury, rupture may occur adjacent to the esophageal hiatus, near the bare area of the liver on the right side, and in a subxyphoid location on either side.

After blunt injury, most ruptures occur in the left hemidiaphragm.12 A review of 32 published series with 1589 patients by Asensio et al.2 showed a distribution of left-sided rupture in 1187 patients (75%), right-sided rupture in 363 patients (23%), and bilateral rupture in 39 patients (2%). This observation parallels the authors’ experience. The relative protection of the right hemidiaphragm, historically, has been attributed to the protective effects of the liver, which blunts the rapid rise in the intraabdominal against the right hemidiaphragm.13 A less common explanation may reflect a weaker left hemidiaphragm that undergoes a later intrauterine closure14; an inherent tendinous or muscular weakness, however, has not been demonstrated with carefully constructed bursting tests.15 The site of injury with penetrating wounds may be anywhere. Bilateral perforations are more likely with missiles. Stab wounds are more commonly located along the periphery of the diaphragm.8

SEVERITY OF INJURY

The severity of diaphragmatic rupture or injury is best judged by the organ injury scale for diaphragmatic injury developed by the American Association for the Surgery of Trauma.16 This scale identifies five grades of injury. Grade I injury is a contusion or hematoma without rupture. Grade II injury is a laceration less than 2 cm in diameter. Grade III rupture is a laceration greater than 2 cm but less that 10 cm in magnitude. Grade IV rupture is greater than 10 cm or has loss of diaphragmatic tissue, which is less than 25 cm2. Grade V injury is an extensive tear with tissue loss greater than 25 cm2.

Patients with penetrating stab wounds and gunshot wounds likely have minor ruptures (grades I and II); some patients with low-velocity missile perforations will have grade III perforations. Patients with blunt injury are more likely to have grade III or grade IV lacerations. The massive injuries with extensive tissue loss (grade V) are more likely to be caused by a close-range shotgun blast, high-velocity rifle perforation, or explosions.17,18

DIAGNOSIS OF DIAPHRAGMATIC INJURY

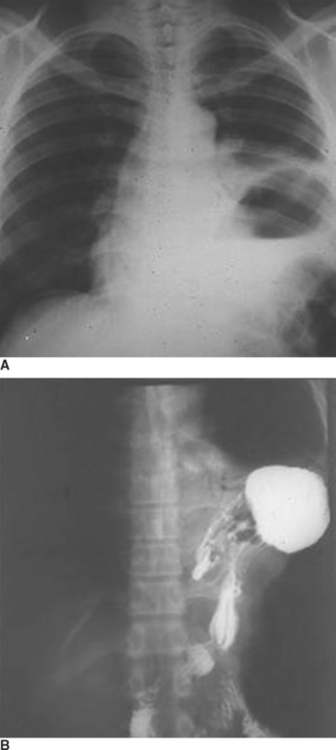

The diagnosis of diaphragmatic rupture after blunt injury is usually made on the basis of a chest x-ray that demonstrates the gastric bubble in the left hemithorax (see Figure 6). This can easily be confirmed to be the gastric bubble by showing that the nasogastric tube will pass up into the thorax and contrast agent injected through this tube will fill the gastric bubble. Because a routine chest x-ray is obtained in all patients with significant blunt injury, this provides the simplest and quickest method of diagnosis.2,7,19 Patients with multisystem injuries involving the chest and pelvis in the presence of hypotension, are more likely to have an associated diaphragmatic injury.20 When the diaphragmatic perforation is not appreciated on the initial chest x-rays, a subsequent computed tomography (CT) scan of the trunk may show the injury; the diagnosis of diaphragmatic rupture by CT, however, is not very sensitive.21 The features which lead to the diagnosis being made or suspected by chest x-ray include obfuscation of the costal phrenic angle, apparent elevation of the hemidiaphragm, and the presence of the gastric bubble in a location that is too superior to be intra-abdominal (see Figure 6). Although not readily apparent, the spleen and splenic flexure of the colon, with or without omentum, are also commonly relocated into the left thorax after blunt diaphragmatic rupture.2,8

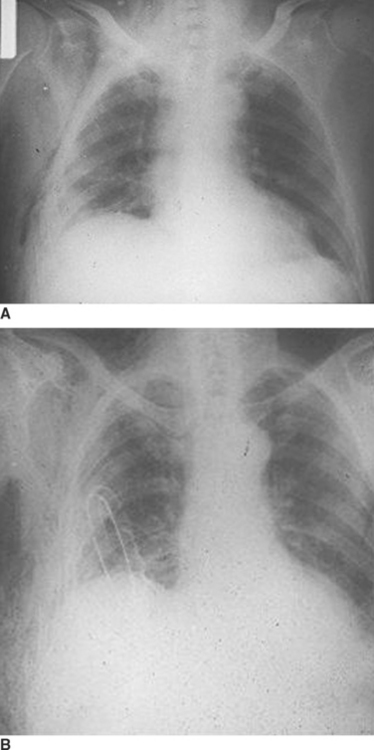

When the blunt injury occurs on the right side, the liver may prevent abdominal viscera from entering the right hemithorax with the result that the injury may be overlooked.7 Patients presenting with blunt trauma and significant bleeding from a right-sided pneumothorax, however, should be suspected of having a right-sided hemidiaphragmatic tear in the bare area of the liver, which is also injured and is the source of bleeding (Figure 7). Bilateral diaphragmatic rupture is much less frequent but, when present, may lead to a delay in diagnosis resulting from the apparent lack of diaphragmatic elevation on either side. Both costophrenic angles, however, show lack of clarity (Figure 8). Repeat chest x-rays in such patients will typically show further elevation of one or both hemidiaphragms (see Figure 8). The elevation on the left side would be more likely to show an intrathoracic gastric bubble even in patients after a delay in diagnosis. When the chest x-ray shows what appears to be a large rupture of the left hemidiaphragm in a patient who has minimal symptoms, one should obtain a good history to rule out previous anatomic changes of the left hemidiaphragm and, if possible, obtain old chest x-rays that might identify the presence of an eventration (see Figure 8).

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree