104 Delirium and Dementia

• Delirium is a medical emergency (not a psychiatric emergency) that can be superimposed on a chronic condition such as dementia.

• Because delirium is associated with high mortality, especially in the elderly, early recognition and treatment are essential.

• A systematic, detailed evaluation, including cognitive assessment, is critical to the diagnosis of delirium and differentiation of delirium from dementia.

• Hypoglycemia and hypoxia are easily identified and reversible causes of delirium.

• Infections and medication effects are common causes of delirium, and the management plan must focus on identifying and treating these processes.

Epidemiology

Altered mental status affects 5% to 10% of patients seen in the emergency department (ED) and in up to 30% of the older population.1 Delirium and dementia account for a significant proportion of the altered mental status. Hustey and Meldon reported that of 78 ED patients with changes in mental status, 62% had cognitive impairment without delirium and the remaining 38% had delirium.2 In a study at a single tertiary care center, it was found that emergency physicians (EPs) missed the diagnosis of delirium in up to 75% of patients older than 65 years; either the condition was misdiagnosed or the patients were discharged home.3 Some studies suggest a mortality rate as high as 9% in patients who are admitted to the hospital because of altered mental status. One study found that patients who were discharged home with unrecognized delirium had a mortality of 30.8% at 6 months.4 The challenge for the EP, who has not generally seen the patient previously, is recognizing delirium—an acute process—when it is superimposed on dementia—a chronic process. Therefore, a systematic approach to ED evaluation is necessary.

Alzheimer dementia is the most common form of dementia in adults (occurring in 50% to 60% of patients), followed by vascular dementia (15% to 25%), Lewy body dementia (5%), and Parkinson dementia (5%).5,6

Delirium

Pathophysiology

The exact mechanism of delirium is not known, but it is believed to arise from an imbalance of neurotransmitters at the cortical and subcortical levels. The principal neurotransmitters implicated in causing delirium include dopamine, an excitatory neurotransmitter, and acetylcholine and γ-aminobutyric acid, inhibiting neurotransmitters.7 Physiologic stressors such as infection, medications, and metabolic disturbances can alter the balance of the levels of neurotransmitters and lead to changes in cognition and attention. Inflammatory mediators such as cytokines and histamines are thought to be involved as well.

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

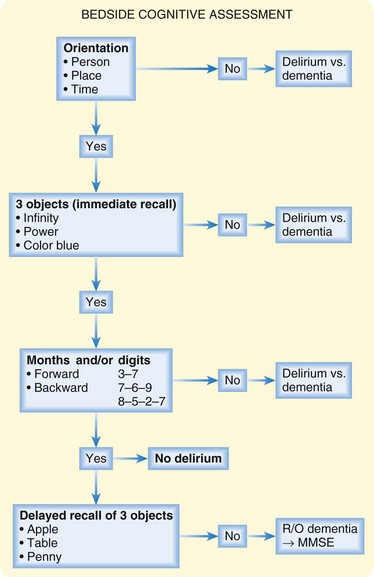

Delirium is a syndrome and not a specific disease; therefore, identifying the underlying cause requires a comprehensive approach that includes a medical and family history, physical examination, bedside cognitive assessment, and diagnostic testing. The confusion assessment method is a useful tool to screen for delirium in the medical setting.8 In an uncooperative or severely confused patient, information obtained from emergency medical service personnel and the patient’s family, personal items brought in with the patient, and a detailed physical examination with close attention to vital signs are important. Figure 104.1 provides a structured approach to assessing cognition at the bedside; patients who are oriented with immediate recall and the ability to sustain attention and recite months or digits in reverse but no delayed recall are unlikely to have delirium and should be suspected of having dementia.8 The EP should consider all possible reversible medical causes of delirium so that treatment can be initiated as soon as possible (Box 104.1).

Box 104.1 Causes of Delirium

Drug Toxicity

Many commonly prescribed medications can cause delirium as a result of improper dosing, change in metabolism, intentional overdose, and drug-drug interactions (Box 104.2).9 Family members or the patient’s personal physician may be able to provide valuable information about recent changes in medication dosages or the addition of new medications.