95 Cranial Nerve Disorders

• The 12 cranial nerves supply motor and sensory innervation to the head and neck.

• Cranial nerve disorders generally cause visual disturbances, facial weakness, or facial pain or paresthesias, depending on the nerve or nerves involved.

• Trigeminal neuralgia and Bell palsy are common cranial nerve disorders.

• A thorough history and physical examination should focus on assessing the potential for trauma (skull fracture), tumor, cerebrovascular accidents, vascular derangements (aneurysm, dissection, thrombosis), and infection (meningitis, abscess).

• The presence of concomitant focal neurologic or systemic signs should heighten suspicion for a central rather than a peripheral cause of the neurologic dysfunction.

Epidemiology

Cranial neuropathies are a heterogeneous group of disorders with a variety of causes. Trauma is a common cause, and diabetes and hypertension are common comorbid conditions. Cranial nerves I, VI, and VII are the most frequently affected after minor head trauma.1 Trigeminal neuralgia is a common cause of facial pain that affects approximately 4.5 per 100,000 individuals; women are affected twice as often as men, and it is more common in those older than 60 years.2 Trigeminal neuralgia can be severely debilitating and has been termed the “suicide disease.”3 Bell palsy is the most common cause of acute facial paralysis worldwide. The peak age at incidence has been reported to be between 15 and 45 years,4 but other investigators have noted an increased incidence in individuals older than 70.5,6 Pregnant women and patients with diabetes have an associated increased incidence of the disease. A familial association of Bell palsy is noted in 4% of cases,4 and it can cause both significant psychologic and physical morbidity.

Pathophysiology

Cranial Nerve II (Optic Nerve)

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

Orbital compressive tumors or aneurysms cause mass effects that compromise optic nerve function.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential patterns of visual loss are described in Box 95.1.

Box 95.1 Differential Patterns of Visual Loss

A central retinal etiology of the fovea or optic disk compromises visual acuity or causes central loss of vision in the affected eye only.

Unilateral blindness is usually associated with an optic nerve lesion, and only the affected eye has complete visual field loss.

Unilateral nasal visual field loss can be caused by an internal carotid artery aneurysm compressing the lateral optic chiasm.

Bitemporal hemianopia can be caused by a midchiasmatic lesion.

Homonymous hemianopia from an optic tract lesion causes full contralateral visual field loss in both eyes.

Homonymous quadrantanopia secondary to a Meyer loop lesion causes contralateral one-quarter visual field loss in both eyes.

Cranial Nerve III (Oculomotor Nerve)

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

Cranial nerve III palsy is more common in patients older than 60 years and in those with diabetes or hypertension (Fig. 95.1).

Patients with herniation syndromes will have a history of trauma (Fig. 95.2), tumor, or other neurologic findings.7

Pain associated with unilateral mydriasis should alert the emergency physician (EP) to look for an aneurysm involving the terminal internal carotid artery. Computed tomographic angiography is more reliable than magnetic resonance angiography.8

Patients with an abscess or cavernous sinus thrombosis may have headaches, altered mental status, and seizures. This diagnosis should be considered in patients with signs and symptoms in the contralateral eye, previous sinus or midface infection, fever, chemosis, eyelid or periorbital edema, and exophthalmos. Extension of internal carotid artery dissection intracranially into the cavernous sinus can result in third, fourth, and sixth cranial nerve palsies.9

Cranial Nerve IV (Trochlear Nerve)

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

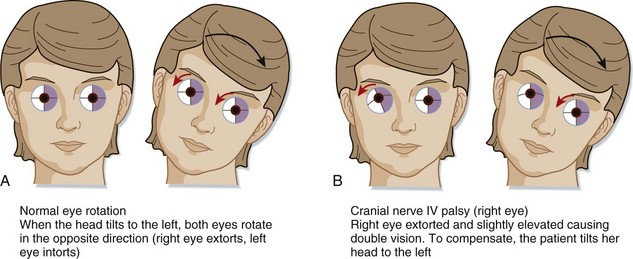

Patients with a fourth cranial nerve palsy have double vision exacerbated by looking downward. The classic complaint is difficulty going down stairs. Most commonly, a history of trauma is reported. On physical examination the patient may unconsciously tilt the head away from the affected side (Fig. 95.3). Etiologic mechanisms are similar to those for the third cranial nerve and include inflammatory processes, trauma, and vascular causes.10

Cranial Nerve V (Trigeminal Nerve)

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

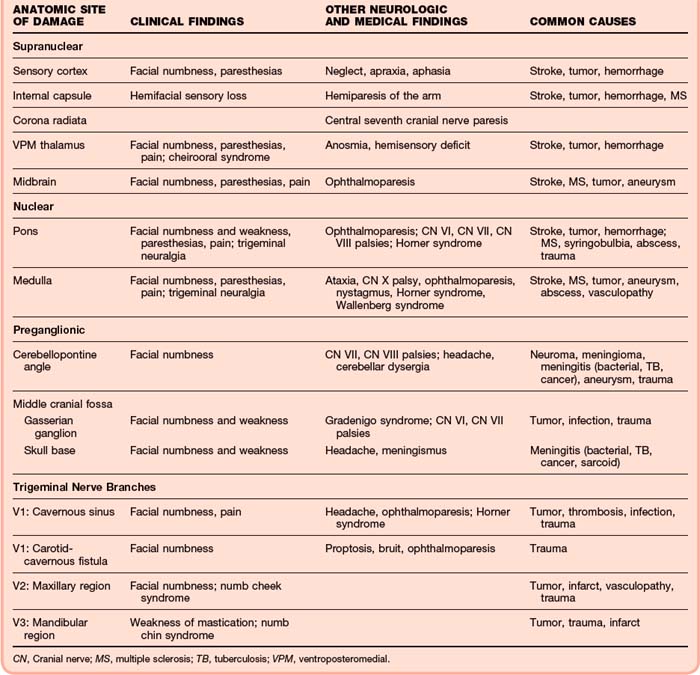

The presence of associated cranial nerve deficits (III, IV, IV, or any combination of these nerves) suggests cavernous sinus involvement. In the setting of trauma, if a bruit over the orbit can be detected, a carotid–cavernous sinus fistula may be present. Associated involvement of cranial nerve VII or VIII or gait ataxia should raise suspicion for a cerebellopontine angle or lateral pontine tumor (Table 95.1).

Associated Horner syndrome may indicate a cervical or lateral brainstem lesion.

The main categories of trigeminal nerve dysfunction are trigeminal neuralgia and trigeminal neuropathy. A sudden onset of symptoms should raise suspicion for a vascular, traumatic, or demyelinating cause, whereas a more indolent course suggests tumor or inflammation (Table 95.2).

Table 95.2 Selected Specific Causes Associated with Trigeminal Nerve Disorders

| ETIOLOGIC CATEGORY | SELECTED SPECIFIC CAUSES |

|---|---|

| Structural Disorders | |

| Developmental | Brainstem vascular loop, syringobulbia |

| Degenerative and compressive | Paget disease |

| Hereditary and Degenerative Disorders | |

| Chromosomal abnormalities, neurocutaneous disorders | Hereditary sensorimotor neuropathy type I, neurofibromatosis (schwannoma) |

| Degenerative motor, sensory, and autonomic disorders | Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis |

| Acquired Metabolic and Nutritional Disorders | |

| Endogenous metabolic disorders | Diabetes |

| Exogenous disorders (toxins, illicit drugs) | Trichloroethylene, trichloroacetic acid |

| Nutritional deficiencies, syndromes associated with alcoholism | Thiamine, folate, vitamin B12, pyridoxine, pantothenic acid, vitamin A deficiencies |

| Infectious Disorders | |

| Viral infections | Herpes zoster, unknown |

| Nonviral infections | Bacteria, tuberculous meningitis, brain abscess, Gradenigo syndrome, leprosy, cavernous sinus thrombosis |

| HIV infection, AIDS | Opportunistic infection; abscess, herpes zosterStroke, hemorrhage, aneurysm |

| Neurovascular Disorders | |

| Neoplastic Disorders | |

| Primary neurologic tumors | Glial tumors, meningioma, schwannoma |

| Metastatic neoplasms, paraneoplastic syndromes | Lung, breast; lymphoma, carcinomatous meningitis |

| Demyelinating Disorders | |

| Central nervous system disorders | Multiple sclerosis, acute demyelinating encephalomyelitis |

| Peripheral nervous system disorders | Guillain-Barré syndrome, chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathyTolosa-Hunt syndrome, sarcoidosis, lupus, orbital pseudotumor |

| Autoimmune and Inflammatory Disorders | |

| Traumatic Disorders | Carotid-cavernous fistula, cavernous sinus thrombosis, maxillary/mandibular injury |

| Epilepsy | Focal seizures |

| Headache and Facial Pain | Raeder neuralgia, cluster headache |

| Drug-Induced and Iatrogenic Neurologic Disorders | Orbital, facial, dental surgery |

AIDS, Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus.

From Goetz CG, editor. Textbook of clinical neurology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2003.

Trigeminal Neuropathy

Until proved otherwise, neuropathies of cranial nerve V, the chin (numb chin; V3), and the suborbital region (numb cheek) should be presumed to be due to malignancies.11