Corneal Abrasion and Foreign Bodies

Lori A. Weichenthal

Corneal abrasions and foreign bodies are among the most frequent ocular conditions that present to the emergency department (ED). It is estimated that the incidence of nonpenetrating injuries to the eye is 15.7 per 100,000 persons per year (1). Although a corneal abrasion is usually a self-limited process, a persistent corneal foreign body or undiagnosed intraocular foreign body can cause unnecessary morbidity.

The emergency physician (EP) must be able to accurately diagnose and treat corneal abrasions and foreign bodies to reduce pain and prevent complications such as infection, ulceration, and vision loss. It is also important that the EP be aware of the potential for intraocular foreign body and be attentive to the historical and physical clues that suggest ocular penetration. This chapter provides an overview of the evaluation and management of corneal abrasions, corneal foreign bodies, and intraocular foreign bodies in the ED.

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

Corneal abrasions and corneal foreign bodies often present with a similar history. The patient often reports that something struck or flew into the eye, followed shortly by the development of pain. At times, the patient does not recall feeling an object entering the eye, but he or she reports being in a situation where such a possibility exists (using a leaf blower, sawing wood, grinding metal, etc.). Contact lenses may also cause corneal abrasions, because of prolonged wear, an improper fit, foreign material under the lenses, or trauma associated with the placement or removal of the lenses. Some patients develop recurrent corneal erosions, which are characterized by pain upon awakening, usually at the site of a recent abrasion.

Whether a foreign body is present, the patient often complains of a persistent foreign body sensation. With this sensation, there is usually pain, tearing, photophobia, blepharospasm, and a minimal decrease in visual acuity. A headache may also be present but is usually mild.

An intraocular foreign body should be suspected when there is a history of a high-velocity injury to the eye. The injury may be caused by a blast effect or activities such as grinding metal or jack hammering cement without the use of protective eyewear. Patients with intraocular foreign bodies usually present with similar symptoms as patients with corneal abrasions or foreign bodies, although they often describe more visual disturbances.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

The differential diagnoses of corneal abrasion, corneal foreign body, and intraocular foreign body should include all the disease processes that present with an acute red eye. For a complete discussion of the red eye, please refer to Chapter 56. When there is no history of a foreign body or trauma, the concern for an infection, inflammatory reaction, or acute angle-closure glaucoma should be heightened.

Infections of the conjunctiva (conjunctivitis) and the cornea (keratitis) are most common and are usually viral or bacterial, but in immunocompromised patients, fungal keratitis is also possible. Patients with eye infections will have symptoms similar to those described for corneal abrasions and foreign bodies. They may also describe mucopurulent discharge and other symptoms of infection (cough, congestion, etc.). The pain associated with eye infections also tends to be more gradual in onset or is first noticed upon awakening (2).

Autoimmune and inflammatory disorders can also cause symptoms similar to those of corneal abrasions and foreign bodies. Anterior uveitis and scleritis are two examples. Patients with these disorders often have other systemic complaints that will help the EP in differentiating them from simple abrasions and foreign bodies.

Acute angle-closure glaucoma can present with a painful red eye. This disease process, however, is usually associated with a severe, unilateral headache and decreased visual acuity, which differs from abrasions and foreign bodies.

In contact lens wearers, although corneal abrasions are common, concern for more serious injury and infection should be heightened. Corneal ulcers and infectious keratitis can occur. Chemical irritation caused by the preservatives in contact lens solutions or the enzymes used to clean some contact lenses can also lead to symptoms similar to corneal abrasions or foreign bodies.

In the setting of trauma, the differential should include corneal or scleral lacerations, hyphema, globe rupture, and traumatic iritis (see Chapter 25). Corneal or scleral lacerations range from simple partial-thickness lacerations to injuries that penetrate the eye. When the laceration is extensive and deep enough, the injury is considered a ruptured globe, which is an ophthalmic emergency. Traumatic iritis can present with symptoms very similar to corneal abrasion and foreign bodies; however, it usually occurs after significant blunt trauma and is associated with headache, photophobia, and decreased vision. If the history is of a high-velocity impact to the eye, intraocular foreign body should always be suspected.

In patients presenting with the story of multiple episodes of corneal abrasions, the diagnosis of recurrent corneal erosions should be entertained. Recurrent corneal erosions often occur in people with epithelial basement membrane dystrophy and/or a history of trauma (3).

ED EVALUATION

When a patient presents to the ED with the complaint of a foreign body sensation to the eye, the history should focus upon the preceding events and a description of all symptoms, including pain, redness, visual changes, or discharge. The time of onset and progressions of symptoms should also be elicited. If the history suggests an actual foreign body, the suspected type of foreign body (wood, metal, organic material, etc.) as well as the setting (high velocity vs. low velocity) should be determined. Previous injuries or surgeries to the eye should be documented, as should the use of glasses or contact lenses. A thorough review of systems and a general medical history should be obtained to evaluate for systemic illness. If nothing in the history suggests a possible systemic problem or multisystem trauma, the physical examination can be focused on the eye.

Visual acuity should be measured as soon as possible. In patients with corneal abrasions and foreign bodies, the visual acuity is frequently normal or mildly decreased. When an intraocular foreign body is present, the visual loss can be significant. The use of a topical anesthetic (proparacaine 0.5% solution or tetracaine 0.5% solution), one to two drops in the affected eye, will make the patient more comfortable and aid the EP in the examination. The use of topical anesthetic can also be helpful in making the correct diagnosis. If the anesthetic does not relieve the patient’s pain, it suggests that the pathology is deeper than the corneal epithelium.

A complete examination of the eye should follow instillation of the topical anesthetic. For a detailed discussion of the eye examination, please refer to Chapter 54. Patients with a corneal abrasion or foreign body often have a slightly swollen eyelid, and the conjunctiva and sclera will be hyperemic. It is particularly important to search the corneal and conjunctival surfaces for a foreign body. This examination should be done under magnification with a bright light or a slit lamp. As the superior tarsal plate is a common place for foreign bodies to lodge, lid eversion should be performed in all patients when suspicion of a foreign body exists. To perform lid eversion, ask the patient to look down, grasp the eyelashes of the upper lid, pull the lid down and out, place a cotton-tipped applicator horizontally above the tarsal plate, and fold the upper lid over the applicator to expose the underlying conjunctival surface (4).

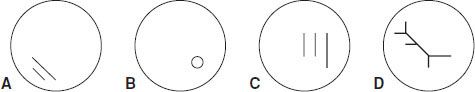

Also of importance in evaluation of the patient with a suspected corneal abrasion or foreign body is an examination with fluorescein. Fluorescein will permanently stain soft contacts, so they should be removed before instilling fluorescein. The patient should be advised to refrain from wearing contacts for several hours. Fluorescein should be instilled in the eye, and the patient should be asked to blink several times. The eye should then be examined with a cobalt blue light or a Wood lamp. Defects of the corneal epithelium will appear green. Particular patterns of uptake can suggest specific injuries. A simple abrasion from a low-impact foreign body will often appear as a single linear uptake. Uptake of multiple linear markings perpendicular to the eyelid suggests a retained foreign body in the superior tarsal plate. A dendritic lesion viewed on fluorescein examination should suggest herpes keratitis. Corneal ulcers and infectious keratitis may appear on fluorescein examination as corneal staining with surrounding opacification (Fig. 57.1).

FIGURE 57.1 Corneal fluorescein uptake patterns for particular injuries. A: Typical abrasion. B: Abrasion around a corneal foreign body. C: Abrasion from a foreign body under the lid. D: Herpetic dendritic lesion.