109 Connective Tissue and Inflammatory Disorders

• Dry eyes and dry mouth unrelated to a medication side effect suggest primary Sjögren syndrome.

• Loss of sensation, paresthesias, and pain in the digits on exposure to cold or emotional stress are characteristics of Raynaud phenomenon.

• Many patients in whom systemic sclerosis eventually develops are initially found to have symptoms of Raynaud phenomenon and symmetric, nonpitting digital edema (without any fibrosis).

• Gastrointestinal symptoms in the presence of symmetric, digital edema or fibrosis suggest systemic sclerosis.

• Symptoms of edema and fibrosis proximal to the elbows or knees can represent an aggressive, diffuse form of systemic sclerosis with a high likelihood of internal organ involvement.

• An angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor should be considered for hypertensive patients with a presumed or definite diagnosis of systemic sclerosis.

• The diagnosis of sarcoidosis should be suspected in patients with only bilateral hilar lymphadenopathy on chest radiography, especially if they either have long-standing pulmonary complaints or are entirely asymptomatic.

• Early, vague subjective symptoms of fatigue, joint pain, or muscle discomfort may herald autoimmune disease.

Sjögren Syndrome

Pathophysiology

Activation of the innate immune system, possibly in response to environmental or as yet unrecognized infectious triggers, results in elevated levels of type 1 interferon and characteristic cytokine profiles, including increased B-cell–activating factor. The ensuing infiltration of the salivary or lacrimal glands by periductal and periacinar foci of aggressive T lymphocytes marks the adaptive immune response. What follows is destruction and eventual loss of exocrine function.1 In addition to T cells, polyclonal activation of B cells within and at the border of foci can result in hypergammaglobulinemia.

More recently, animal models suggest that lacrimal and salivary gland dysfunction need not always rely on innate and adaptive inflammation as a prerequisite. Rather, they may be related to abnormalities in water and ion channels as a result of genetic, hormonal, or autonomic imbalances antecedent to the inflammatory response.2 Other exocrine glands in the body (lining the respiratory tree, integument, and vagina) can also be affected in Sjögren syndrome and produce a dry cough, dry skin, dysuria, or dyspareunia.

Differential Diagnosis and Medical Decision Making

If dry eyes and dry mouth dominate the clinical picture, the patient may have primary Sjögren syndrome. However, these symptoms can be associated with a number of other autoimmune disorders that more accurately characterize the clinical findings (rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, scleroderma), in which case such patients probably have secondary Sjögren syndrome (Box 109.1).

Box 109.1 Differential Diagnosis of Sjögren Syndrome

Most Common

Medication effects (antihypertensives, antipsychotics, antihistamines, antidepressants)

Viral sialadenitis, human immunodeficiency virus, human T-cell lymphotropic virus type I

Lacrimal gland infiltration in sarcoidosis or amyloidosis

Chronic sialadenitis, conjunctivitis, blepharitis

Malnutrition (alcoholism, bulimia)

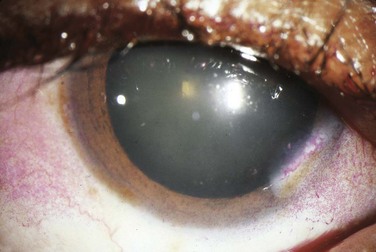

The cracker test, in which the patient tries to chew and swallow a dry cracker, is probably the most useful bedside diagnostic maneuver. Patients with Sjögren syndrome will have a difficult time completing this task, with adherence of food to the buccal mucosa. Slit-lamp testing with fluorescein may show epithelial defects over the cornea consistent with keratitis secondary to dryness. Rose bengal staining (Fig. 109.1) is generally regarded as a more sensitive means of depicting these defects but is usually performed by an ophthalmologist. The Schirmer test involves placing standardized tear testing strips between the unanesthetized eyeball and the lateral margin of the lower lid and noting advancement of a tear film over a period of 5 minutes. Anything less than 5 mm is considered abnormal.

Treatment

Xerophthalmia

Artificial tears with or without preservatives may be used throughout the day, and lubricating ointments can be used at night. Oral pilocarpine, 5 mg four times per day, will stimulate muscarinic gland receptors, increase lacrimal flow, and provide subjective improvement.3,4 More severely affected patients with keratoconjunctivitis sicca who are taking cevimeline, 30 mg three times per day, have reported a reduction in the severity of symptoms.5,6 Topical ocular nonsteroidal and steroidal preparations or topical 0.05% cyclosporine can be prescribed by an ophthalmologist for a short term.5 Occlusion of the nasolacrimal duct temporarily with plugs or permanently by surgical intervention is last-line therapy.

Xerostomia

Though available, artificial saliva tends to be short-lived and less well accepted by patients. Meticulous oral hygiene is necessary to prevent dental caries, gingivitis, or periodontitis secondary to dryness. Sugarless sialogogues (lemon drops) stimulate flow. Lifestyle modifications such as the use of a humidifier or avoidance of dry environments and excessive air conditioning can help retain moisture. Mycostatin oral suspension, Mycostatin vaginal tablets (also dissolve orally), or clotrimazole troches should be considered for the treatment of oral candidiasis in patients with Sjögren syndrome. Oral pilocarpine, 5 mg four times per day, or cevimeline, 30 to 60 mg three times per day, can stimulate muscarinic receptors and improve salivary flow in those with more significant symptoms.5,7–9 One must beware of side effects related to systemic muscarinic activation, including bradycardia, bronchospasm, gastrointestinal symptoms, or impaired mydriasis and trouble with night vision.

Autoimmune Lymphocyte Activity

Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) can be prescribed from the emergency department (ED) for symptomatic control of minor rheumatic complaints. Hydroxychloroquine has no clear benefit in ameliorating these symptoms.5 The rheumatologist may prescribe prednisone, methylprednisolone, cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, or azathioprine to control lymphocyte activity. Newer therapies include monoclonal antibodies (rituximab) that target B cells.5 Future investigations are directed at blocking type 1 interferon, B-cell–activating factor, and other cytokines that link the initial innate immune response to the subsequent adaptive response composed of activated lymphocytes.

Systemic Sclerosis (Scleroderma)

Epidemiology

Systemic sclerosis is a generalized thickening and fibrosis of the skin and internal organs that affects 1 in 4000 adults in the United States.10 Its incidence ranges from 2 to 23 cases per million per year.11 Women are more likely to be affected than men, with the onset of disease peaking between 30 and 50 years of age.

Pathophysiology

Patients can have localized patches of skin fibrosis, or the disorder may progress to diffuse skin involvement with fibrosis and dysfunction of internal organs. Although the precise trigger is not known, an underlying functional and microstructural vascular abnormality is believed to play a central role. In association with oxygen radical species, findings include endothelial cell dysfunction and apoptosis, an imbalance favoring endothelin over prostacyclin, vascular smooth muscle hyperplasia, and pericyte proliferation in the perivascular space. Concomitantly, an adjacent inflammatory response occurs and is composed of lymphocytes, macrophages, and fibroblasts that lay down increasing amounts of extracellular matrix, including collagen.12 Cytokines and growth factors such as transforming growth factor-β and platelet-derived growth factor are involved in the amplification of this response, which includes activation and differentiation of fibroblasts.10 The types of systemic sclerosis are listed in Box 109.2.

Box 109.2 Types of Systemic Sclerosis

Localized scleroderma consists of fibrosis in scattered, circular patches of skin (morphea), linear streaks (linear scleroderma), or nodules and is seen primarily in children. There is no systemic or internal organ involvement, and sequelae are cosmetic and sometimes functional.

Limited systemic sclerosis implies that fibrosis occurs distal to the elbows or knees and above the clavicles only. It is generally slowly progressive.

CREST syndrome previously referred to a fibrotic process that involved the skin, digits, and esophageal wall. Patients have calcinosis cutis, Raynaud phenomenon, esophageal dysmotility with symptoms of reflux and dysphagia, sclerodactyly, and telangiectasia. This particular classification is no longer commonly used.

Diffuse systemic sclerosis is characterized by fibrosis extending proximal to the elbows and knees. It may be rapidly progressive and can be associated with significant internal organ fibrosis.

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

Skin findings are the most useful in the ED. Edema is a hallmark of early scleroderma, as well as rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, and other connective tissue disorders. Painless swelling of the fingers and hands is common (Fig. 109.2). Erythema and pruritus are associated findings caused by an early inflammatory response and deposition of components of the extracellular matrix. Nonpitting edema need not be limited to the distal end of extremities but may spread proximally or to the face and neck over the course of weeks.

Fig. 109.2 Changes in the hands associated with connective tissue diseases.

A, Edematous phase. B, Atrophic phase with contractures and skin thickening (sclerodactyly).

(From Goldman L, Ausiello D, editors. Cecil textbook of medicine. 22nd ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2004.)

Fibrosis can ensue in weeks or months. Gradually, collagen is deposited and the edematous areas are replaced by firm, thick, taut skin that may become bound to underlying tissue. In the fingers, tight skin can produce joint flexion contractures plus breaks or ulcerations as it is stretched over bony prominences (knuckles) in the condition termed sclerodactyly (see Fig. 109.2

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree