CHAPTER 66 COMPARTMENT SYNDROMES

Compartment syndrome is a diagnosis that demands a decision. The diagnosis should be followed by immediate operation. Whether it occurs in a limb or the abdomen, compartment syndrome is a crisis that can be averted by surgical decompression. Fasciotomy treats compartment syndrome in limbs and laparotomy in the abdomen. Any alternative treatment should be compared with that standard.

Abdominal compartment syndrome (ACS) occurs in patients with massive intra-abdominal injuries and hemorrhagic shock. In the abdomen, elevated compartment pressure is manifested by oliguria and reduced cardiac output that do not improve with intravascular fluid replacement and increased airway pressures. Organ impairment and increased airway pressure can be detected at a pressure of 15 mm Hg. At 25–30 mm Hg, organ failure is evident and immediate laparotomy should be performed.1 Measuring intra-abdominal pressures will confirm the diagnosis.

INCIDENCE

Trauma, vascular, and orthopedic surgeons will likely diagnose and treat compartment syndrome because of its association with vascular injury and fractures. The incidence is relatively low, even though the presentation and treatment are dramatic and memorable. In our Level 1 trauma center, the overall incidence of compartment syndrome was 0.004 among trauma admissions over a 2-year period.2 This number includes compartment syndrome in the leg, arm, and abdomen.

Other published reports suggest that the incidence is much higher. A review of leg injuries reported an incidence of 30%–35% (up to 64%) of popliteal artery injuries with knee dislocations.3 A large series of brachial artery injuries reported 12.1% incidence of fasciotomy.4 Ivatury et al.5 reported 100% incidence of ACS among patients with damage control laparotomy and primary fascial closure. The incidence was reduced to 38% with open abdomen techniques.5 Improvements in open abdomen techniques and widespread appreciation of the syndrome have reduced the incidence of ACS even further. The low incidence of compartment syndrome among all trauma patients should not mitigate vigilance in patients with high-risk injuries.

MECHANISM OF INJURY

Arterial occlusion followed by reperfusion injury is a common presentation. Long bone fractures often precipitate compartment syndrome because of hematoma and tissue swelling at the site. Gulli and Templeton6 report that it occurs in 3%–17% of closed tibia fractures. Compartment syndrome associated with femur injuries is rare if the fracture occurs at the shaft and absent associated vascular injuries.7,8

Venous pathology also causes compartment syndrome. There are several reports of compartment syndrome occurring with phlegmasia cerulea dolens.9–11 The muscle compartments deserve attention in these patients.

In the upper arm and forearm, compartment syndrome can occur with supracondylar humerus fractures, IV drug abuse, electrical injuries, complications of IV sites, prolonged tourniquet use, and even weight lifting.12 Many of these patients will present in ambulatory settings, where the index of suspicion may be low. Deep pain and tense swelling of the limb should prompt further investigation.

Abdominal compartment syndrome often develops in trauma patients who have had laparotomies and resuscitation for hemorrhagic shock. The abdominal cavity will stretch anteriorly and superiorly (along the diaphragm) to accommodate visceral edema or accumulating blood until it reaches the limits of its compliance. At this point, the abdomen becomes a rigid compartment, and pressure rises sharply, impairing organ function. Increased vascular resistance and reduced venous return impair cardiac output. Reduced renal perfusion pressure causes oliguria. Encroachment into the chest and tension on the diaphragm increase ventilator and airway pressures. Loss of functional residual capacity (FRC) and ventilation-perfusion mismatch (V/Q) cause hypoxia.13

Intoxications and systemic disease can cause compartment syndrome. Rutgers et al.14 reported four cases of nontraumatic rhabdomyolysis and compartment syndrome in young male alcoholics receiving treatment with benzodiazepines. Ergotamine and cocaine intoxication have also been implicated in cases of compartment syndrome.15,16 Patients with type I diabetes mellitus can suffer spontaneous compartment syndrome.17–19

Systemic diseases or drugs that cause vasoconstriction can induce muscle ischemia and subsequent compartment syndrome. Local factors that increase mass within the inelastic fascial compartments can also raise intracompartment pressure sufficiently to cause the feared syndrome. These include hematoma, fluid injection, infection, and even metastatic melanoma.20 The careful clinician should remember the pathology, not only the common clinical settings, for compartment syndrome.

DIAGNOSIS

Physical Examination

The combination of inordinate muscle pain, pain on passive motion, muscle weakness or paralysis, hyperesthesia, and tense muscle compartments have been well described and repeated to generations of surgery residents.21–23 Recognition of the symptom constellation should prompt immediate measurement of compartment pressure. If accurate measurements cannot be performed, or if the results are conflicting, then clinical diagnosis should supersede. Once the diagnosis has been made, the patient should not suffer delay in fasciotomy.

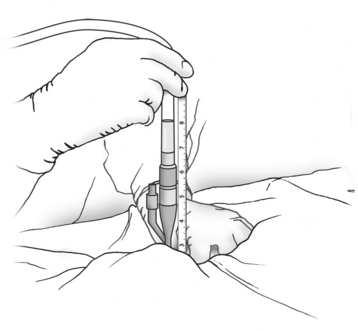

Abdominal compartment syndrome should be suspected in the patient with a tense, distended abdomen within a few hours after laparotomy for trauma or massive bleeding. Visceral swelling or continued bleeding push abdominal compliance beyond its limits. Oliguria that does not respond to fluid boluses is an early sign of intra-abdominal hypertension (IAH), and should prompt measurement of intra-abdominal pressure. This can be accomplished easily at the bedside by measuring the bladder pressure through a Foley catheter1,9 (Figure 1). Frequent ventilator alarms from high airway pressures as the ventilator pushes against abdominal pressures of 60 cm H2O or more herald the final stages of ACS. In this case, immediate abdominal decompression should be performed, even at the bedside, to permit ventilation and oxygenation.

Compartment Measurements

There are several techniques for measuring compartment pressures.24–26 There are two variations—wick and slit—of the catheter technique. The catheters are inserted into the muscle through large-bore needles and then connected to a pressure transducer or manometer via saline-filled tubing. Because insertion and connection of the catheters are cumbersome, measuring several compartment pressures is difficult. The new electronic transducer-tipped catheter is promising, but shares many of the shortcomings with the other catheter techniques, such as need for tubes, catheter kinking, and poor placement beneath the fascia.27 Other techniques for measuring compartments are readily available at the bedside and are easier to use.

Manufactured pressure monitors such as the Stryker (Stryker Instruments, Kalamazoo, MI) (Figure 2) employ modifications of the needle technique. They measure the pressure directly through a needle inserted into the muscle compartment. They are self-contained units requiring no assembly, which makes multiple measurements easier at various sites or at different times. If a manufactured monitor is not available, a homemade version can be assembled using an 18-gauge needle, saline-filled pressure tubing, and a manometer or transducer.

Noninvasive Methods

There is a tenacious search for noninvasive diagnostics, and it extends to compartment syndrome. Several techniques that have clinical utility in other settings have been tried here. Near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS) has been studied.28–30 It measures muscle perfusion, not pressure, and can reliably diagnose ischemic tissue. Oxyhemoglobin saturation of less than 60% correlates with muscle compromise of compartment syndrome. Champions for its use argue that it directly identifies ischemic tissue rather than compartment pressure, which is a proxy for tissue compromise. If clinicians monitor for tissue ischemia rather than a rise in pressure, unnecessary fasciotomies might be prevented. Conversely, skeptics argue that waiting until ischemia is manifest may delay surgery. Also, the probe’s range is limited to 2 cm or less below the skin surface. Therefore, it may miss deep muscle ischemia.

Digital pulse-oximetry is commonly available in the emergency room, operating room, and the intensive care unit. It is easy to use and inexpensive. It is not, however, sensitive in diagnosing compartment syndrome and muscle ischemia. It relies on pulsatile arterial flow to the distal digit to accurately measure the hemoglobin oxygen saturation. Because the arterial blood measured in the toe or finger bypasses the muscle compartments, measuring the former gives little useful information of the latter. A clinical series by Mars and Hadley31 confirms this theoretical limitation.

Scintigraphy using 99mTc-methoxyisobutyl isonitrile (99mTc-MIBI) has been used to diagnose chronic exertional compartment syndrome.32,33 The study requires a stable, ambulating patient, a trip to the nuclear medicine department, and a repeat study the next day with the patient at rest. With these limitations, nuclear medicine is no help with trauma patients.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree