INTRODUCTION

GUNSHOT WOUNDS

Gunshot injuries can be accurately identified and classified as entrance, atypical entrance, exit, or atypical (grazing) wounds based upon their physical characteristics. Wounds are not classified based upon their size. Physical findings in and around these wounds may offer evidence as to the actual mechanism of injury, supporting or refuting the initial history given to the provider. As most physical findings are transient in nature (cleaned, debrided, or eventually healed), the emergency physician must be diligent in recognizing and documenting them at the time of presentation. The physician’s failure to accurately document the physical characteristics of the wounds or correctly interpret the physical findings can compromise the legal process and obstruct justice.

Gunshot wounds of entrance are divided into four categories based on their range of fire: distant, intermediate, close, and contact. Range-of-fire is the distance from the gun’s muzzle to the victim’s skin or clothing.

The size of the entrance wound bears no relation to the caliber of the inflicting bullet. Entrance wounds over elastic tissue will contract around the tissue defect and have a diameter much less than the caliber of the bullet.

Distant Wounds: The distant wound is inflicted from a range sufficiently distant that the bullet is the only component expelled from the muzzle that reaches the skin. There is no visible tattooing or soot deposition associated with a distant entrance wound. As the bullet penetrates the skin, friction between it and the epithelium results in the creation of an “abrasion collar” (Fig. 19.1). The width of the abrasion collar will vary with the angle of impact. Elongated abrasion collars from projectiles that enter on an angle may produce a collar with a “comet tail” (Fig. 19.2). Most entrance wounds will have an abrasion collar; however, gunshot wounds to the palms and soles are exceptions—their entrance wounds appear slit-like. Bullets that pass through an intermediate object, a door or windshield for example, will become deformed or misshapen (Fig. 19.3). A misshapen bullet creates an irregular abrasion collar (Fig. 19.4) as compared to the smooth abrasion collar created by a nondeformed bullet (Fig. 19.1).

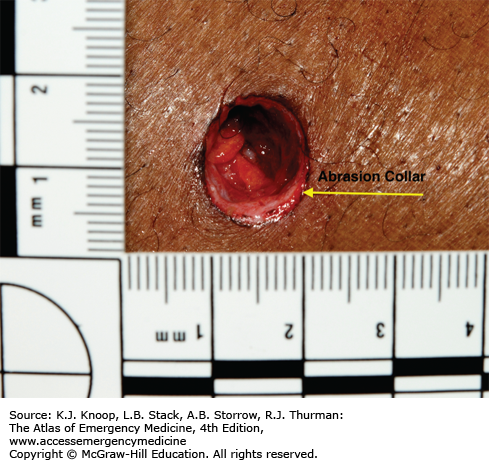

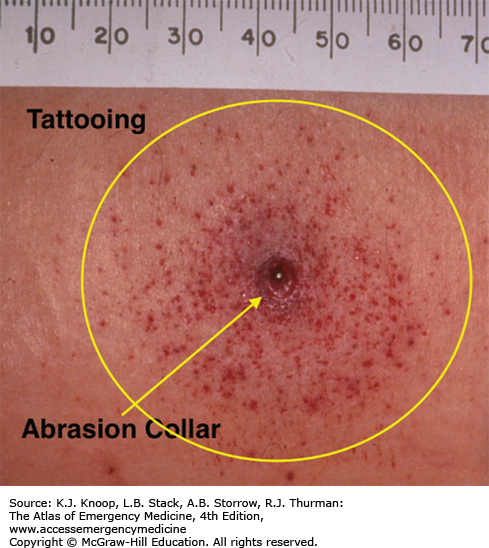

FIGURE 19.1

Distant Gunshot Wound. An abrasion collar surrounds the wound defect and is created from the friction of a bullet passing through the skin. All entrance wounds will have an abrasion collar with the exception of entrance wounds to the palms and soles. The lack of soot, seared skin, or gunpowder tattooing confirms this is a “distant” range of fire. (Photo contributor: William S. Smock, MD.)

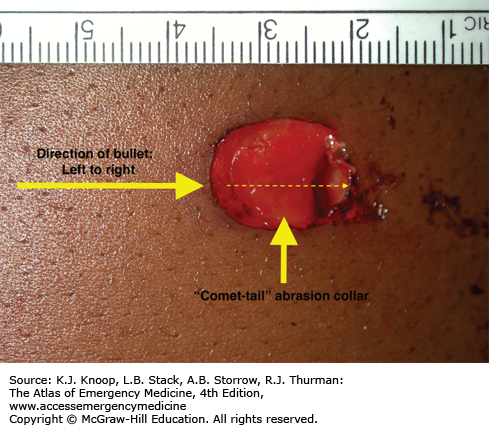

FIGURE 19.2

“Comet-Tailed” Abrasion Collar. The “comet tail” abrasion collar located on the lateral aspect of the wound indicates that the bullet entered the wound at an angle. The “comet tail” also indicates the bullet’s direction of travel: from left to right. (Photo contributor: William S. Smock, MD.)

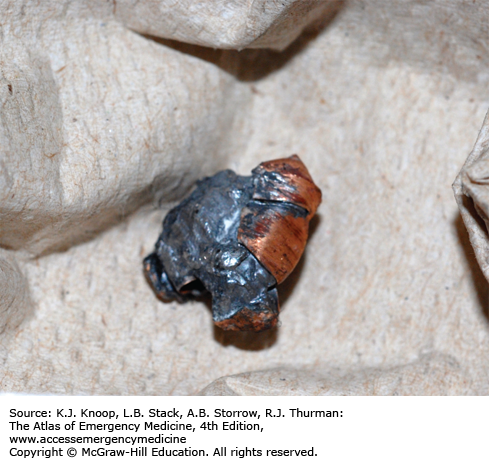

FIGURE 19.3

Deformed Bullet. This bullet passed through a car windshield and deformed prior to striking the suspect in the arm. The bullet’s irregular shape created the atypical abrasion collar associated with the entrance wound seen in Fig. 19.4. (Photo contributor: William S. Smock, MD.)

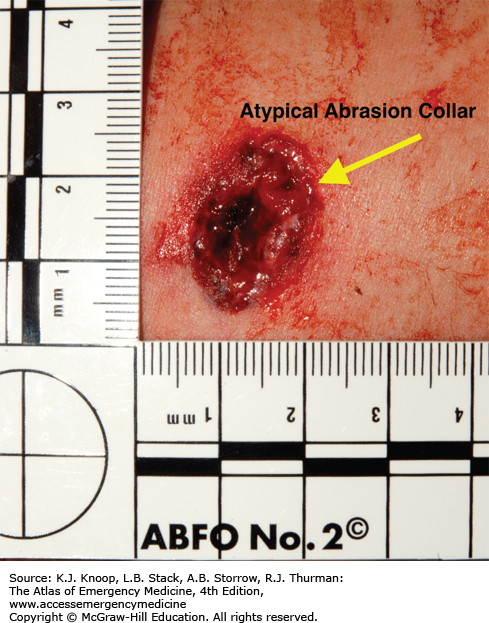

FIGURE 19.4

Atypical Abrasion Collar. When a bullet passes through an intermediate object, ie, a door or windshield, it can become deformed or misshapen with an irregular surface. When a misshapen bullet (Fig. 19.3) passes through skin, the abrasion collar it generates appears irregular and jagged when compared to the smooth one caused by the nondeformed bullet (Figs. 19.1 and 19.2). (Photo contributor: William S. Smock, MD.)

Intermediate-Range Wounds: Tattooing is pathognomonic for an intermediate-range gunshot wound and presents as punctate abrasions from contact with partially burned or unburned grains of gunpowder (Fig. 19.5). This tattooing cannot be wiped away. Clothing and hair, as intermediate objects, may prevent the gunpowder grains from making contact with the skin. Tattooing can, but rarely does, occur on the palms and soles owing to the thickness of their epithelium.

FIGURE 19.5

Intermediate-Range Gunshot Wound. Punctate abrasions present on the skin are the result of impact from gunpowder that is either wholly or partially unburned. This phenomenon is termed tattooing or stippling. Tattooing is pathognomonic for intermediate-range (less than 48 inch) gunshot wounds. (Photo contributor: William S. Smock, MD.)

Tattooing has been reported with a range of fire as close as 1 cm and as far away as 4 feet. The density of the abrasions and the associated pattern will depend upon the barrel length, muzzle-to-skin distance, type of gunpowder (ball, flattened ball, or flake), presence of intermediate objects, and caliber of the weapon. Spherical powder travels farther and has greater penetration than flattened ball or flake powder. “Pseudotattooing” (Fig. 19.6) is punctate abrasions from fragments created when bullets pass through intermediate objects like wood or glass.

Close-Range (Near-Contact) Wounds: “Close range” is defined as the maximum range at which soot is deposited on the clothing (Fig. 19.7) or wound (Fig. 19.8) and typically is a muzzle-to-victim distance of 6 inches or less. On rare occasions, however, soot has been found on victims as far as 12 inches from the offending weapon. The concentration of soot will vary inversely with the muzzle-to-victim distance and its appearance will be affected by the type of gunpowder and ammunition used, the barrel length, the caliber, and the type of weapon.

FIGURE 19.7

Soot and Bullet Wipe. Soot is the carbonaceous residue from the burning of gunpowder. Soot is associated with close-range wounds, 6 inches or less. Bullet wipe is residue and/or lead from the surface of the bullet that is transferred to clothing or skin. Bullet wipe can be seen at any range of fire. Clothing should be collected and packaged in separate paper bags for submission to the crime laboratory. (Photo contributor: William S. Smock, MD.)

Contact Wounds: A contact wound occurs when the barrel or muzzle is in contact with the skin or clothing as the weapon is discharged. Contact wounds can be described as tight, where the muzzle is pushed hard against the skin, or loose, where the muzzle is incompletely or loosely in contact with the skin or clothing. Wounds sustained from tight contact with the barrel can vary in appearance from a small hole with seared, blackened edges (from the discharge of hot gases and an actual flame), to a gaping, stellate wound (from the expansion of the skin from gases) (Figs. 19.9 and 19.10). Large stellate wounds are often misinterpreted as exit wounds based solely upon their size and without adequate examination of the wound characteristics.

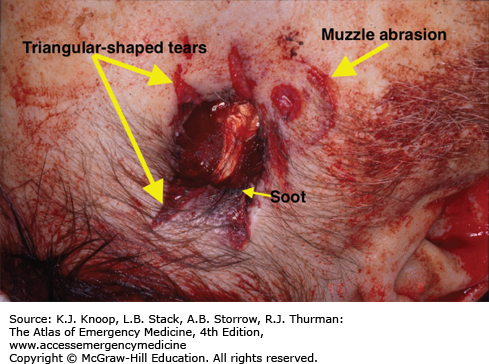

FIGURE 19.9

Contact Gunshot Wound with Muzzle Abrasion. A contact gunshot wound to the right temple from a 9 mm semiautomatic handgun. Note the triangle-shaped tears, soot, seared wound margins and a muzzle-abrasion at the 2-o’clock position. The muzzle abrasion or muzzle imprint was the result of the injection of gases into the skin, causing a rapid and forceful expansion of the skin against the barrel. (Photo contributor: William S. Smock, MD.)

In a tight-contact wound, all materials—the bullet, gases, soot, incompletely combusted gunpowder, and metal fragments—are driven into the wound. If the wound overlies thin or bony tissue, the hot gases will cause the skin to expand to such an extent that it stretches and tears. These tears will have a triangular shape, with the base of the tear overlying the entrance wound. Larger tears are associated with ammunition of .32 caliber or greater, or magnum loads.

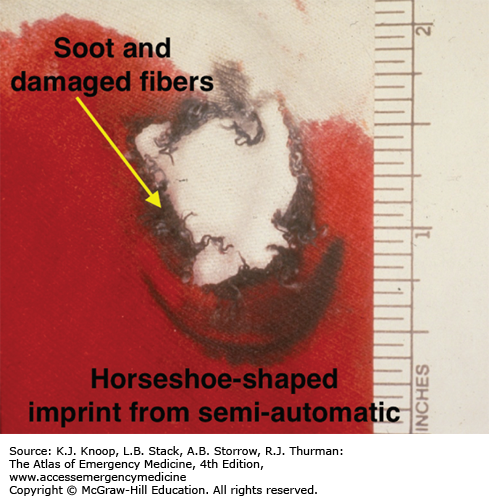

Stellate tears are not pathognomonic for contact wounds. Tangential wounds, ricochet or tumbling bullets, and some exit wounds may also be stellate in appearance. These wounds are distinguished from tight-contact wounds by the absence of soot and powder within the wound. In some tight-contact wounds, expanding skin is forced back against the muzzle of the gun, causing a characteristic pattern contusion called a muzzle contusion (Fig. 19.9). An outline of the barrel can also be imprinted on the overlying clothing and is associated with contact wounds through clothing (Fig. 19.11). These patterns are helpful in determining the type of weapon (revolver or semiautomatic) used to inflict the injury and should be documented prior to wound debridement or surgery.

FIGURE 19.11

Muzzle Imprint, Soot, and Seared Fibers. The clothing exhibits a “horseshoe-shaped” soot mark reflecting the outline of the frame of a semiautomatic handgun. Seared fibers are the result of flame and hot gases expelled from the barrel when it is in contact with clothing. (Photo contributor: William S. Smock, MD.)

With a loose-contact wound, where the muzzle is angled or held loosely against the skin, soot and gunpowder residue will be present in and around the wound. The angle between the muzzle and skin will determine the soot pattern. A perpendicular, loose-contact or near-contact injury results in searing of the skin and deposition of the soot evenly around the wound. A tangential loose or near-contact injury produces an elongated searing pattern and deposit of soot around the wound.

“Bullet wipe” is a residue from soot, soft lead, or lubricant, which may leave a gray or black rim or streak on the skin or clothing overlying an entrance wound (Fig. 19.7). This discoloration may also be found around the abrasion collar but is usually more prominent on clothing.

Determining whether a wound is an entrance or an exit wound should be based on the physical characteristics and physical evidence associated with the wound and never upon the size of the wound. The size of the exit wounds are the result of a bullet pushing and stretching the skin from inside outward. The skin edges are generally everted, with sharp but irregular margins (Figs. 19.12, 19.13, 19.14). Abrasion collars, soot, searing, and tattooing are not associated with exit wounds. Soot can be seen at an atypical exit wound site if the entrance wound is close to the associated exit wound. Soot can be propelled through the wound from entrance to exit when the wound track is extremely short. If this is noted, the soot deposition will be more pronounced at the entrance and only faintly observed within the exit wound.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree