Gynecologic

Endometriosis

Pelvic inflammatory disease, chronic endometritis, chronic salpingitis

Pelvic congestion syndrome

Ovarian remnant syndrome

Residual ovary syndrome

Vulvodynia

Vulvar vestibulitis

Vaginismus

Urologic

Interstitial cystitis/painful bladder syndrome

Chronic urethritis

Gastrointestinal

Irritable bowel syndrome: constipation-dominant, diarrhea-dominant, mixed

Chronic constipation

Dyspepsia

Musculoskeletal

Pelvic floor tension myalgia, including levator spasm, piriformis syndrome

Abdominal wall trigger points

Low back pain

Temporomandibular joint disorder

Fibromyalgia

Neurologic

Peripheral neuropathies

Headaches, migraines

Endometriosis

The presence of endometrial glands and stroma documented outside of the uterine corpus occurs in approximately 15 % of reproductive-aged women [8]. Notwithstanding the relatively high prevalence of this disorder, may women remain asymptomatic. This feature is somewhat critical to the surgeon who incidentally notes endometriotic lesions at the time of surgery for non-pain indications. It is absolutely acceptable to leave these lesions undisturbed; however, if preoperative symptoms are suggestive of endometriosis, which is subsequently encountered, then surgical management is recommended. Typical symptoms include progressively worsening menstrual cramps that often begin quite painfully at menarche (dysmenorrhea), deep pain with intercourse (dyspareunia), dyschezia (pain with bowel movements), or chronic, noncyclic pain that occurs regardless of timing during the menstrual cycle. Endometriosis can also contribute to infertility. Although we are focusing on reproductive-aged women, endometriosis has been documented in many stages of life, from premenarcheal to postmenopausal years.

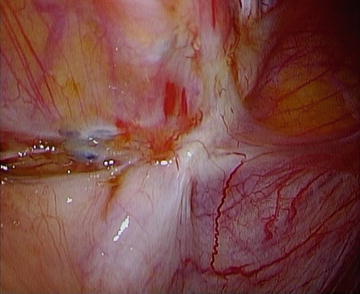

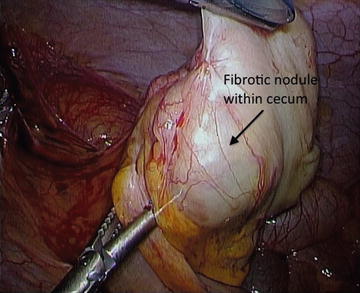

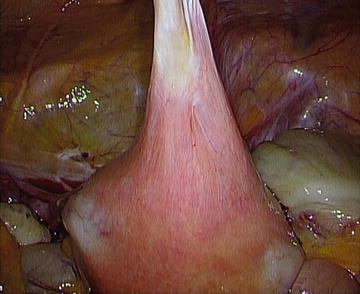

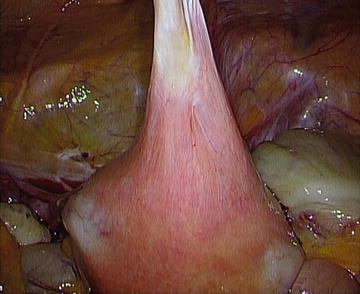

Endometriosis is characteristically described as a disease that affects peritoneal surfaces and the ovary (seen as endometrioma , or “chocolate cysts ”), but it also represents an inflammatory process, whereby chronic fibrosis and infiltrating disease can occur. Sampson originally described his theory of retrograde menstruation in the early twentieth century, but most menstruating women will demonstrate this phenomenon [9]. It has been suggested that women with endometriosis then have a deficiency in their cell-mediated immune response, and foreign bodies, such as menstrual effluent passed retrograde through the oviducts, remain untargeted after being exposed to peritoneal surfaces [10]. Repeated exposure, facilitated stromal infiltration, and an activated inflammatory response result in the development of persistent lesions that can manifest in a myriad of ways from small peritoneal blebs to peritoneal fibrosis. See Figs. 12.1, 12.2, 12.3, and 12.4 for varying types of disease seen at laparoscopy.

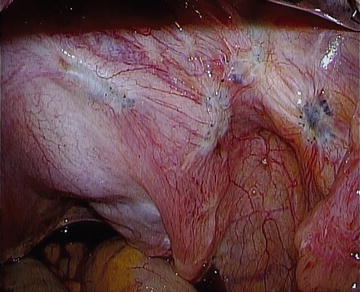

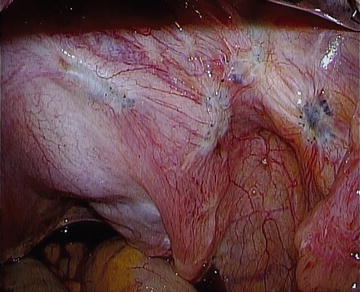

Fig. 12.1.

Endometriosis as peritoneal blebs in the midline posterior cul-de-sac.

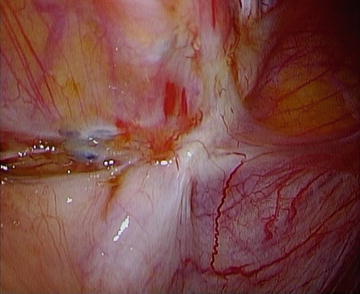

Fig. 12.2.

Endometriosis as powder burn lesions in right ovarian fossa.

Fig. 12.3

Endometriosis as fibrotic lesions on pelvic brim (white ridge).

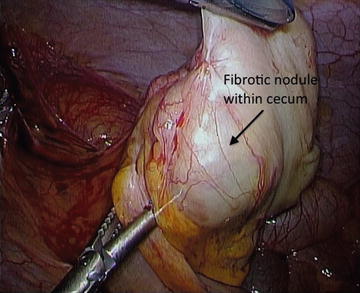

Fig. 12.4.

Fibrotic cecal nodule with proven endometriosis (obliterated appendix).

Endometriosis is a disease state most readily diagnosed with a good history and physical examination. A tender, retroverted, and fixed uterus can be suggestive of deeply infiltrating endometriosis (DIE) that distorts normal and mobile pelvic anatomy. However, physical findings may also be unremarkable. Patients with progressively worsening pain complaints who are often refractory to first-line agents raise a diagnostic flare. This process is often aided by simple measures such as transvaginal ultrasound (TVUS) . TVUS is used to evaluate for ovarian or the occasional bladder infiltrative disease, which is clinically useful because treatment options, to be discussed later, would then differ. Pelvic exam is a relatively poor predictor for DIE, but TVUS is consistently more effective than more sophisticated and expensive tools such as MRI [11]. Surgery with histopathologic confirmation has been the historical gold standard for diagnosing endometriosis; however, treatment can be initiated based on clinical suspicion alone without visual confirmation.

Traditional first-line therapies used to manage pain from endometriosis include pharmacological agents that suppress endogenous steroid hormone production [12–15]. Table 12.2 provides a summary of medical options.

Table 12.2.

Medical options for treating endometriosis-associated pain.

Medication | Route of administration | Notes |

|---|---|---|

Combined oral contraceptives (COCs) | Cyclic or continuous oral daily use | Lack high-quality clinical trials No agent seems to be more effective than another |

Progestins | Continuous oral daily use (Norethindrone acetate 5–20 mg daily; Medroxyprogesterone acetate (5–100 mg daily)) Intramuscular depot form (150 mg IM q 3 months) Intrauterine (levonorgestrel-intrauterine system; LNGIUS) | Reduction in pain compared to placebo in clinical trials Depot form no more effective with more side effects Intrauterine administration effective even for DIE with fewer side effects |

Androgens | Daily oral, vaginal or intrauterine | Not all forms available in the US Untoward androgenic side effects especially with oral forms |

Gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists (GnRH-a) | Intramuscular depot (leuprolide acetate 3.75 mg IM [1 month], 11.25 mg [3 month]) | Reduction in pain compared to placebo in clinical trials Comparable to COCs and progestins Positive response in empiric trial Hormonal add-back therapy required after 6 months of use to minimize side effects (vasomotor symptoms, reduction in bone mineral density); can be initiated immediately |

Aromatase inhibitors | Daily oral use | Limited data, but may be effective in reducing pain for DIE Use with progestins or GnRH-a to prevent ovarian follicle development |

Most operative strategies used to treat women with symptomatic endometriosis focus on conservative measures designed to preserve reproductive options. Hysterectomy with bilateral adnexectomy and excision of infiltrating disease, however, may have the potential to eliminate pain in women with refractory symptoms [16]. Any therapy short of hysterectomy predisposes women to recurrent symptoms. Laparoscopic ablation or excision of endometriotic lesions has been evaluated in a number of clinical trials, with up to 80 % of women reporting significant improvement in pain symptoms [17]. Notwithstanding adequate trial design, these studies documented a 30 % placebo effect; the difference, however, was that the therapeutic benefit was much longer-lasting for those in the treatment arms [18].

DIE is not consistently recognizable by the unfamiliar surgeon, and since depth of infiltration correlates with pain symptoms, excising these lesions seems more logical [19]. Ovarian endometrioma, often associated with DIE, are better managed by enucleating the cyst rather than ablation [20, 21]. Data to support postoperative suppression are limited, although the benefits of surgery may be extended with combined oral contraceptives (COCs), progestins, or gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists (GnRH-a).

Adenomyosis

Adenomyosis is an enigmatic disorder characterized anatomically as endometrial glands and stroma existing within the myometrium diffusely. Focal lesions are referred to as an adenomyoma . Although traditionally gynecologists have considered adenomyosis a cause of heavy, prolonged, and/or painful menses, it is apparent from studies of hysterectomy specimens for a spectrum of benign disorders that adenomyosis is an extremely common entity, found in approximately 25–65 % of hysterectomy specimens.

Until relatively recently, adenomyosis was something diagnosed based on clinical suspicion and confirmed only at the time of hysterectomy. Advances in uterine imaging have provided the clinician with the opportunity to diagnose this entity with reasonable accuracy. In the relatively small uterus, TVUS is an effective means of identifying adenomyosis, assuming adequate sonographer skill and real-time evaluation of the study, as opposed to review of still images [21]. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may be an effective secondary tool used to confirm adenomyosis, especially when the uterus is large or associated with concomitant uterine myoma.

The relationship between adenomyosis and abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB) or CPP remains unclear, in particular because many trials were performed to evaluate symptom reduction without performing a hysterectomy. The levonorgestrel intrauterine system (LNG-IUS) has proved to be more effective than other modalities in quality of life measures when compared to hysterectomy in a randomized trial [22].

Adhesions

There is a tendency to associate pelvic adhesions with CPP, but there is very little evidence that a clear relationship exists. The exception may be for dense connections involving viscera, but the lack of control groups for surgical studies weakens the cause-and-effect association, and the therapeutic benefits are more difficult to quantify [23]. As an example, Fig. 12.5 demonstrates a thick adhesion between the uterus and anterior abdominal wall after Cesarean section. Clinical trials to determine the incidence of such adhesions, its correlation with pain, and recurrence after adhesiolysis would require second-look laparoscopic evaluation; such trials have not been approved to date. Current recommendations focus on the implementation of microsurgical techniques to minimize the risk of de novo adhesions. When adhesions are encountered during surgical exploration in a woman with CPP, seek to identify an underlying cause of adhesions such as endometriosis, and divide only adhesions necessary to accomplish the surgical objectives.

Fig. 12.5.

Dense uterine adhesion to anterior abdominal wall from prior cesarean section.

Myofascial and Musculoskeletal Pain

Patients with myofascial pain complain of aching pain that is worse with activity or at the end of the day, and improved with rest or relaxation such as a warm bath. Just as lumbar muscles can be the source of pain in low back pain, pelvic floor muscles can be the source in patients with pelvic pain [24]. Dyspareunia is a common presenting symptom. Evaluation begins with a careful examination of the lower back and sacroiliac joints, and then progresses to a complete abdominal exam. The patient is asked to locate any discrete locus of pain and examine herself with palpation until pain is elicited. At this point, a Carnett maneuver (having the patient contract her rectus muscles by raising her head into a half situp) can be helpful to help distinguish a visceral from a somatic source. Finally, the examiner moves to the pelvic exam, using a single digit to palpate the levator muscles (iliococcygeus, pubococcygeus, puborectalis) just inside the introitus. Moving further back, the obturator is palpated as a square-shaped muscle just deep to levator ani. Finally, the piriformis can be palpated as a rubber-band-like structure that emerges during isometric contraction when the knee is externally rotated at the hip against the examiner’s hand. In each case, the examiner asks the patient if the muscle is tender, if pain is felt at the site or migrates elsewhere, and if the pain experienced is similar to symptoms offered in the history, such as dyspareunia. Trigger point injections can be helpful for abdominal wall pain, but the treatment of myofascial pain is generally physical therapy, where a variety of strength, balance, relaxation, and control modalities are employed. In pelvic pain, referral should be made to a therapist specifically trained to address women’s health and pelvic floor issues.

Pelvic Congestion Syndrome

Similar to the case for pelvic adhesions, high-quality data linking pelvic pain with radiological evidence for pelvic congestion of the gonadal veins are lacking. It has been suggested that faulty valves within these vessels create flow disruption and resultant distention, similar to what has been described for varicoceles in men. Pelvic congestion syndrome (PCS) is not an uncommon finding in women; however, it is not clear if the finding is associated with the complaint of pain. Controlled studies are needed to provide better guidance regarding treatment outcomes [25]. To date, multiple procedures have been described in observational trials and include internal iliac/ovarian vein embolization, sclerotherapy, and ovarian vein ligation.

Ovarian Remnant Syndrome

Women at risk for ovarian remnant syndrome (ORS) , whereby a functional portion of the ovary is inadvertently left in place after oophorectomy, include those in whom the fibrovascular attachments are obscured from dense pelvic adhesions, endometriosis, or reproductive malignancy [26]. Resulting pain symptoms are typically cyclic and are accompanied by a solid pelvic mass with ovarian follicular development. Follicle stimulating hormone (FSH) and serum estradiol levels are in the premenopausal range if bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy was undertaken; however, hormone levels are not conclusively diagnostic. Nonsurgical attempts to manage pain with steroid hormone suppression should first be considered, given the predisposing surgical risks. Properly identifying and resecting the remaining disease can also prove to be extremely difficult, and has not been evaluated sufficiently in clinical trials.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree