27 Chest Pain

Initial Approach

Initial Approach

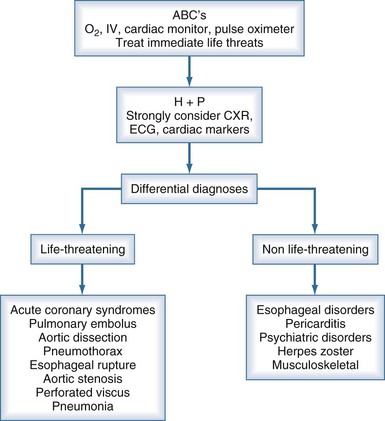

Several life-threatening conditions can cause chest pain in the critically ill, and the initial approach should focus on prompt evaluation and resuscitation of the airway, breathing, and circulation. Assess the patient’s level of consciousness, palpate the pulse, and listen to the breath sounds and heart. Obtain vital signs, including oxygen saturation by pulse oximetry, and ensure that the patient is on a cardiac monitor and has adequate intravenous (IV) access. Adhering to this algorithmic approach (Figure 27-1) in patients with chest pain will ensure that critical conditions such as hypoxemia, hypotension, tension pneumothorax, and unstable ventricular arrhythmias are quickly identified and treated. These conditions, as well as the life-threatening causes of chest pain discussed below, are covered in greater detail in other chapters in this textbook.

History

History

After the initial evaluation and stabilization, obtain a more detailed history. If the patient can communicate, start with an open-ended question like “What’s going on, Mr. Jones?” Physicians typically interrupt patients within 23 seconds, but one should resist this temptation and allow the patient to describe their symptoms.1 Physicians often neglect to ask even basic questions about the quality of chest pain in patients with aortic dissection, and this omission is associated with a delay in diagnosis.2 The mnemonic OLDCAAR can help avoid this mistake (Table 27-1). Ask the bedside nurse about recent changes in the patient’s condition (e.g., changes in mental status, respiratory pattern, or recent medications). Lastly, a quick “chart dissection” should be performed, focusing on the findings noted on initial presentation, reason for ICU admission, past history, and recent progress notes.

TABLE 27-1 OLDCAAR Mnemonic for Evaluating Pain

| Domain | Suggested Questions |

|---|---|

| Onset | Sudden or gradual? Maximal pain at onset? |

| Location | Generalized or localized? Can you point with one finger to where it hurts? |

| Duration | When did it start? Just now, or did the pain occur earlier, but you didn’t want to bother anyone? Is it constant or intermittent? If intermittent, is there a trigger, or is it random? |

| Character | Sharp? Dull? Ache? Indigestion? Pressure? Tearing? Ripping? |

| Associated symptoms | “Dizzy”—vertiginous or presyncopal? Diaphoresis? Palpitations? Dyspnea? Nausea or vomiting? |

| Alleviating/aggravating | Position? Belching? Exertion? Deep breathing? Coughing? |

| Radiation | To the back? Jaw? Throat? Arm? Neck? Abdomen? |

Differential Diagnoses

Differential Diagnoses

Potentially Life-Threatening Causes of Chest Pain

Acute Coronary Syndromes

ACS include unstable angina and ST-segment and non–ST-segment elevation MI. The “classic” symptoms of ACS include chest pressure radiating to the left arm, nausea, and diaphoresis, but the history has several limitations with regard to the diagnosis of ACS. Although certain features (pain radiating down the right arm or both arms) are associated with a higher likelihood of ACS, and other characteristics (pleuritic, positional, or sharp pain) with a lesser likelihood, none of these can reliably confirm or exclude the diagnosis.6,7 Further complicating matters, diabetes, smoking, dyslipidemia, hypertension, and a family history predict the development of heart disease over years in asymptomatic patients but may be less useful in predicting ACS in patients with acute chest pain.8 Reduction in pain after the administration of nitroglycerin is also not a reliable indicator of cardiac chest pain.9 Thus, ACS should almost never be excluded as a cause of chest pain based on the history alone.

Pulmonary Embolism

Approximately 1% to 2% of ICU patients develop deep vein thrombosis (DVT) or PE, but the true incidence is probably higher.10 Unrecognized PE carries a high mortality, but survival improves dramatically with prompt diagnosis and treatment. Chest pain due to PE is usually pleuritic and often associated with dyspnea, hemoptysis, cough, or syncope.11 ICU patients usually have risk factors for PE including immobility, advanced age, recent surgery or trauma, malignancy, and central venous catheterization. Do not be deterred from working up PE in patients receiving subcutaneous heparin, as two-thirds of those with DVT and PE are receiving prophylaxis at the time of diagnosis.10

An elevated arterial-alveolar gradient may be noted on blood gas analysis, but this is a nonspecific finding in the critically ill. The ECG is often normal, but it may show sinus tachycardia, nonspecific ST-segment and T-wave changes, or a right bundle branch block.12 The CXR can be normal but more commonly reveals nonspecific findings such as pleural effusion, infiltrates, or atelectasis.13 Although D-dimer testing has been used to rule out venothromboembolic disease in outpatients with a low likelihood of this diagnosis, the D-dimer assay does not appear to be a particularly useful diagnostic tool in the ICU setting.14 The sensitivity of transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) for PE varies considerably, but the test can be useful in patients who have larger clots that are of hemodynamic significance.15 In such cases, TTE can be performed rapidly at the bedside when patients are unsafe for transport out of the ICU. TTE has the added benefit of assessing the response to thrombolytics by evaluating right heart function and changes in pulmonary artery pressure.15 A ventilation/perfusion scan can be time consuming and difficult to perform in mechanically ventilated patients; its interpretation may be obscured by other lung pathology.16 An IV contrast-enhanced CT of the chest can be performed rapidly, and newer scanners have high sensitivity and specificity, making this the diagnostic study of choice in most ICU patients.

Initial treatment of patients with confirmed PE involves anticoagulation with subcutaneous low-molecular-weight heparin or IV unfractionated heparin. Patients with hemodynamic instability due to PE may require thrombolysis or surgical embolectomy.17

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree