CHAPTER 78

Chemical Neurolysis

INDICATIONS

Neurolytic techniques have long been used in the treatment of pain. The underlying principle for neurolytic blocks is prolonged relief of intractable pain, most often in patients with malignancies. Pain associated with cancer may be visceral, somatic, and/or neuropathic in origin. Many cancer patients have a combination of these pain types at the time of their diagnosis. Pain is often reported when visceral structures are compressed, invaded, or distended. Visceral pain is often described as vague, dull, deep, constricting, crampy, or colicky in nature. Empirical data suggests that visceral sympathetically-mediated pain responds more favorably to neurolytic therapy than neuropathic pain.1

Neurolysis, or destruction of neural tissue, was once performed surgically under direct visualization. As advancements in imaging and ablative techniques continued to progress, these procedures can now be done percutaneously2 chemically, thermally with radiofrequency, or by freezing via cryoneurolysis.

The indications for chemical neurolysis include3:

• Severe, intractable pain that persists after less invasive treatments

• Intolerable side effects of analgesic therapy

• Intrathecal catheter, with or without a pump, is not a viable option

• Advanced or terminal malignancy

• Pain well localized:

![]() Unilateral pain, localized to the trunk

Unilateral pain, localized to the trunk

![]() Involves only a few dermatomes or one peripheral nerve

Involves only a few dermatomes or one peripheral nerve

• Primary somatic pain mechanism

• Absence of intraspinal tumor spread

• Pain relieved with prognostic local anesthetic block

• No undesirable effects after local anesthetic block

• Realistic expectations by patient and family

• Informed consent clearly explains potential complications

BASIC CONCERNS AND CONTRAINDICATIONS

Risks and benefits should always be weighed prior to undergoing any intervention. Extensive communication with the patient is necessary before proceeding.

Some concerns include:

• Potential risk for infection in immunocompromised patients

• Metastatic cancer spread to the region

• Thrombocytopenia secondary to chemotherapy

• Difficulty in positioning due to tumor and pain location

Absolute contraindications for injection include:

• Infection, systemic or localized to injection site

• Coagulopathy

• Patient refusal

Relative contraindications include:

• Autonomic nervous system no longer the main transmission of the pain source for visceral pain (eg, carcinoma of the pancreas that has begun to invade the body wall)

• Distorted or complicated anatomy (eg, large aortic aneurysm)

RELEVANT ANATOMY

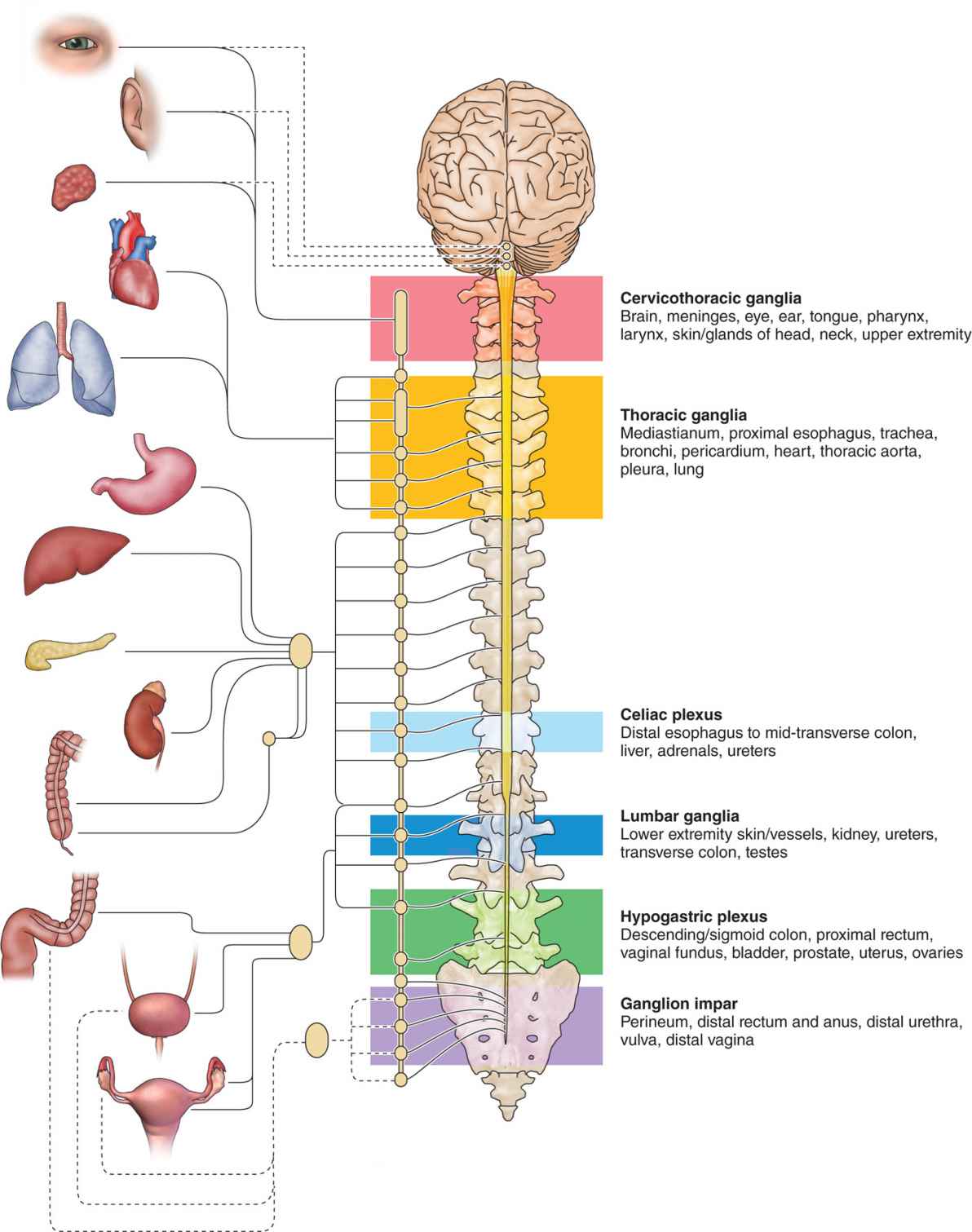

Visceral neurolytic blocks are particularly effective for cancer-related pain. The paravertebral sympathetic chain consists of sympathetic neural tissue from several sympathetic plexuses that run along the paravertebral region of the body (Figure 78-1). There are several sites for neurolytic blockade of the sympathetic nervous system for the treatment of cancer pain (Table 78-1).1 These axial sympathetic chains include the cervical, thoracic, and lumbar sympathetic ganglia.

Figure 78-1. Sympathetic nervous system sites for neurolysis.

TABLE 78-1. Sympathetic Nervous System with Corresponding Anatomic Structures

The sympathetic system receives afferent nociceptive impulses from:

• Visceral fibers of the head and neck and upper extremities (stellate ganglion), cardiothoracic viscera (thoracic sympathetic ganglia)

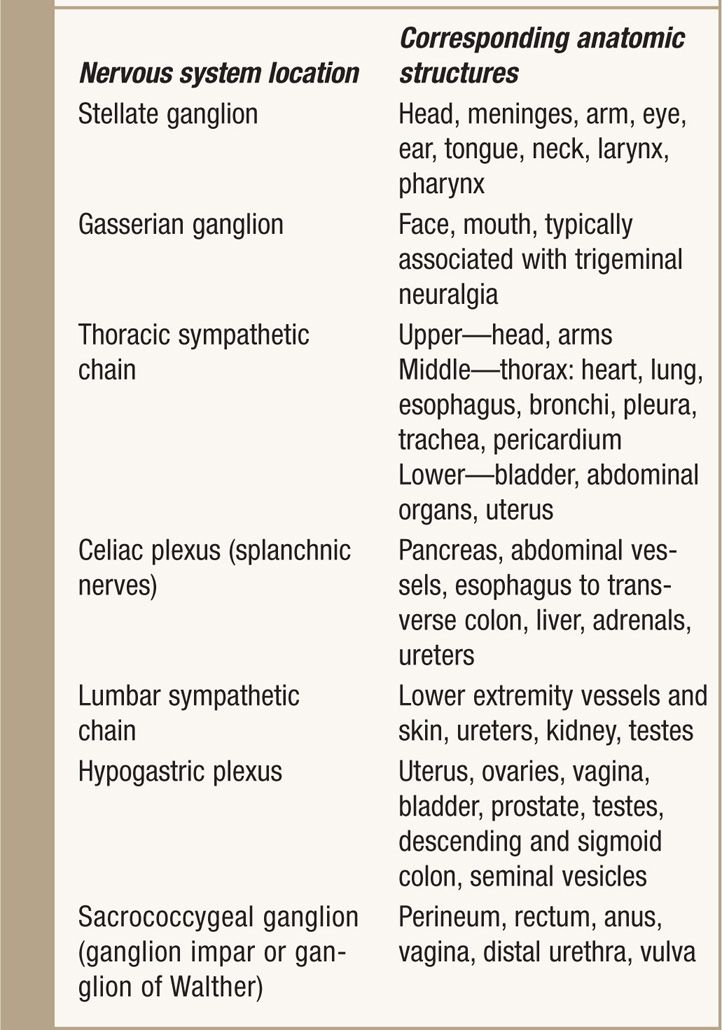

• The abdominal viscera (celiac plexus) (Figure 78-2)

Figure 78-2. CT Image of antecrural celiac plexus block. The arrows indicate the antecrural radiocontrast dye spread of the celiac plexus neurolytic block. A, aorta.

• The urogenital system and lower extremities (lumbar sympathetic ganglia)

• The pelvic viscera (superior hypogastric plexus and ganglion impar)4

With ideal treatment, visceral neurolytic blocks produce satisfying analgesia without motor weakness or somatic sensory loss.

PREOPERATIVE CONSIDERATIONS

• Informed consent and proper explanation of all potential complications.

• Anticoagulation.5,6 This is less of a concern than for an epidural injection but a concern nonetheless as there is inherent disruption of tissue from the introduction of a needle.

• Physical examination of the area for infection, skin ulceration or necrosis, and extent of disease.

• Patient must be able to lie in the intended position for the length of the procedure.

• Intravenous access for IV fluid and medications for sedation or hypotension secondary to sympathetic block or if the patient experiences vasovagal reaction.

• Evaluation for contrast allergy. Utilization of contrast allows for precise needle placement.

Selection of Medications

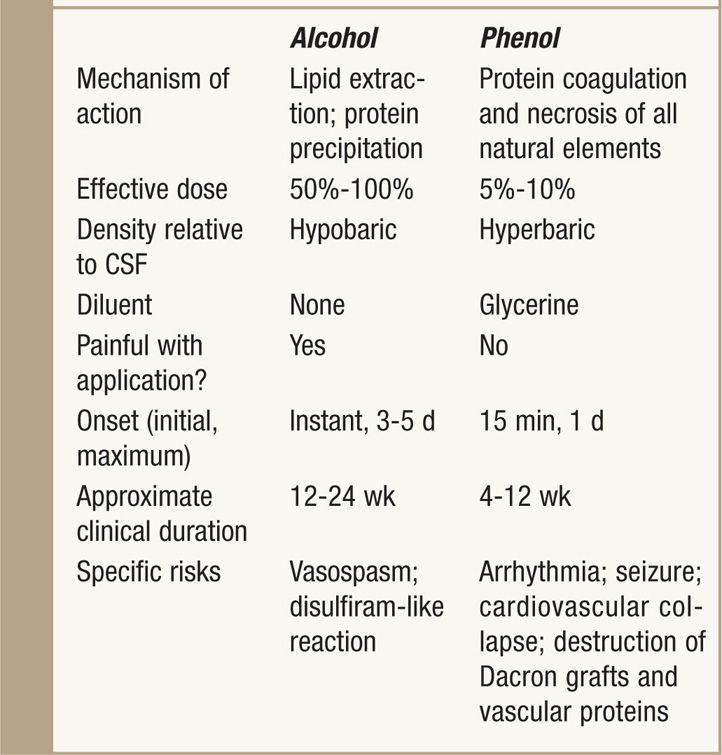

The neurolytic agents [E1]most commonly used are ethyl alcohol (50%-100%) (Figure 78-3) and phenol (5%-10%) (Figure 78-4) (Table 78-2). Alcohol was first used for neurolysis in 1902 in order to treat trigeminal neuralgia. Phenol was introduced in the 1950s and gained widespread popularity, in part because of its analgesic as well as neurolytic properties. These agents disrupt transmission of pain signals by causing Wallerian degeneration distal to the lesion.7 They usually produce a block that lasts 3 to 6 months.

Figure 78-3. Ethyl alcohol. (Used with permission from Michael M. Bottros, MD.)

Figure 78-4. Phenol. (Used with permission from Michael M. Bottros, MD.)

TABLE 78-2. Common Chemical Neurolytic Agents

Alcohol:

• Damages nerves by denaturing proteins and fatty substance extraction and may be associated with neuritis.

• The injection is painful.

• It is hypobaric in comparison to CSF.

• Denser block with longer duration.

Phenol:

• Diffuses into the axon and denatures the proteins causing Wallerian denaturation

• Has some local anesthetic properties

• Unlike alcohol, it is not painful on injection

• It is less water soluble and hyperbaric in comparison to cerebrospinal fluid (CSF).

• The intensity and [E2]duration of block with phenol are less than with alcohol and phenol carries a lower risk of neuritis.7

POSTPROCEDURE FOLLOW-UP

The patient should be followed up by telephone the next day for the potential complications and immediate pain relief secondary to local anesthetic. The chemical neurolysis may not be apparent for up to 1 week. The patient should be advised to call the physician for any procedure-related complications and/or any unexpected neurologic deficit. Patient should be monitored closely for following:

• Weakness

• Urinary or bowel incontinence

• Bleeding

• Numbness

• Exacerbation of symptoms

Monitoring of Potential Complications

• Skin and other nontarget tissue necrosis and sloughing. Secondary to damage of the vascular supply to the skin, causing ischemia and chronic trauma to denervated tissue. Necrosis of muscles, blood vessels, and other soft tissues has also been reported.

• Neuritis. The reported incidence of neuritis is up to 10%.8 It is caused by partial destruction of somatic nerve and subsequent regeneration. Neuritis occurs only if the nerve cell body is not destroyed. It is less likely to occur with a subarachnoid or ganglion neurolytic block. It is clinically manifested as hyperesthesia and dysesthesia that may be worse than the original pain problem. It is one of the limiting factors in the use of chemical neurolysis.

• Anesthesia dolorosa. This is a poorly understood manifestation whereby the patient complains of distressing numbness caused by an imbalance in afferent input. It is caused by long-term loss of afferent input and resultant central nervous system changes. A local anesthetic block done a few hours prior to the performance of the neurolytic block seems to prevent the development of this complication.8 Management of this problem is pharmacotherapy with the use of tricyclic antidepressants and anticonvulsants.

• Prolonged motor paralysis. This can be a major complication and is greatly feared by physicians, patients, and family. It occurs infrequently and may be temporary.

• Perineal and sexual dysfunction. This is another complication that can occur temporarily, specifically with ganglion impar blocks. About 1.4% and 0.2% of patients will have bowel or bladder dysfunction at 1 week and 1 month, respectively.9

• Systemic complications. These include hypotension secondary to sympathetic block and systemic toxic reactions, heart rate and rhythm disturbances, blood pressure changes, and CNS excitation and depression.

CLINICAL PEARLS AND PITFALLS

• The goal of performing a neurolytic block of the sympathetic axis is maximizing analgesia and possibly reducing the dosage of these opioids to alleviate unwanted side effects.

• Opioids may have to be carefully titrated as there is the potential for respiratory depression and narcotic withdrawal syndrome after sudden cessation of pain.

• Needle position should always confirmed with radiologic imaging prior to the injection of a neurolytic agent, as the needle’s tip may be intravascular, in the peritoneal cavity, or in a viscus.

• A complete and careful neurologic examination, especially the extent and duration of any sensory or motor deficits, must be documented both prior to and after the procedure. Should any complications occur, these deficits may resolve over time. Reassure the patient and provide adequate analgesia in such cases.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree