CHAPTER 69 CERVICAL, THORACIC, AND LUMBAR FRACTURES

Spinal column injuries in the United States occur at a rate of 4 to 5.3 injuries per 100,000 households. The most common causes of spinal column injuries include motor vehicle accidents (45%), falls (20%), sports-related accidents (15%), violence (15%), and miscellaneous causes (5%).

NEUROLOGIC INJURY

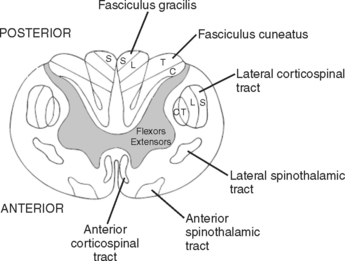

The end of the spinal cord (conus medullaris) is located at L1-L2 intervertebral disk. Below the level of the conus medullaris, the spinal canal is occupied by the lower motor roots called the cauda equina. As a lower motor neuron lesion, injury to the nerve roots has a much better prognosis for recovery than injury to the spinal cord (Figure 1).

Classification of Neurologic Injury

The secondary survey in patients with spinal cord injury includes a precise definition of neurologic deficits. Classification systems are useful to compare outcomes between different studies. While a variety of clinical grading systems exist, the American Spinal Injury Association (ASIA) scale has become the most widely accepted. The ASIA scale identifies motor, sensory, and general impairment deficits, and incorporates the functional independence measure (see page 163).

Incomplete Spinal Cord Syndromes

Four incomplete spinal cord syndromes are defined based on the location of the trauma to the spinal cord. Central cord syndrome is the most common pattern of injury, resulting from gray matter destruction, which is worst in the central region of the spinal cord. This injury pattern often occurs due to hyperextension injury in a patient with degenerative cervical spinal stenosis. The patient experiences motor and sensory deficits that are worse in the upper than in the lower extremities. The overall prognosis for central spinal cord injuries is good, with 75% of the patients experiencing at least partial motor recovery and most regaining the ability to ambulate.

Posterior cord syndrome is the rarest and causes decreased position and pressure sensation.

CERVICAL SPINE TRAUMA

Anatomy

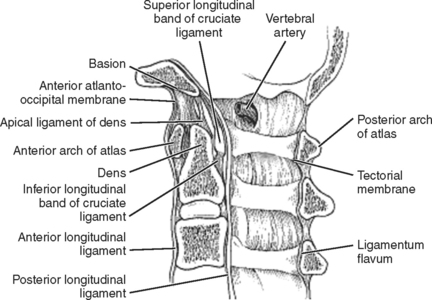

Spinal stability primarily stems from ligament and disk integrity. Craniocervical stability involves intact anterior and posterior atlanto-occipital membranes and articular capsules. The atlantoaxial joint is stabilized by the transverse ligament primarily with the paired alar and apical ligaments provided secondary stabilization. The posterior ligamentum nuchae, interspinous ligaments, and ligamentum flavum acts as a “tension band” to provide resistance against flexion distraction injuries. The atlantoaxial joint provides 50% of the overall cervical rotation (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Sagittal cervical spine cross-section.

(Data from Heller J, Pedlow F: Anatomy of the cervical spine. In Clark CR, Dvorak J, Ducker TB, et al., editors: The Cervical Spine, 4th ed. Philadelphia, Lippincott-Raven, 2005, p. 9.)

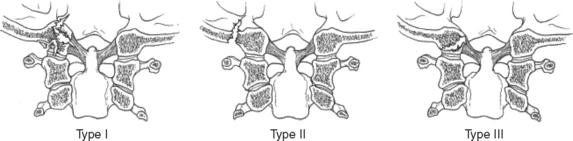

Occipital Condyle Fracture

Stable type I, II, and III fractures can be managed in a cervical collar for 6–8 weeks. Displaced type II or III fractures are managed in a halo vest for 8–12 weeks. Grossly unstable type III fractures require occiput to C2 fusion and should raise the suspicion for an underlying occipitocervical dissociation. Cranial nerve palsies may develop days to weeks after the injury and most frequently involve cranial nerves IX, X, and XI (Figure 3).

Figure 3 Types of occipital condyle fractures.

(From Anderson PA, Mirza SK, Chapman JR: Injuries to the Atlantooccipital articulation. In Clark CR, Dvorak J, Ducker TB, et al., editors: The Cervical Spine, 4th ed. Philadelphia, Lippincott-Raven, 2005, p. 594.)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree