CHAPTER 48 Cardiac Transplantation

DESPITE NUMEROUS advances, heart failure remains a leading cause of morbidity and mortality in the United States. Roughly 5 million Americans are presently afflicted with heart failure, and each year approximately 550,000 new cases are identified.1 Considerable effort, expense, and resources continue to be dedicated to improvements in heart failure prevention and treatment.

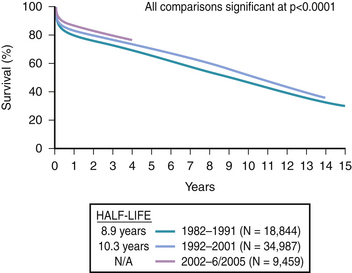

Cardiac transplantation remains the most effective treatment for selected patients with end-stage heart failure. Once transplanted, survival is routine, as shown in Figure 48-1.2 Most infections and rejection episodes are either preventable or treatable. Furthermore, advances in mechanical circulatory support have expanded the candidate pool, enabling additional critically ill heart failure patients to undergo successful heart transplantation.

In recent years, however, the number of cardiac transplants performed has declined to approximately 2000 per year in the United States and 3000 per year worldwide. Transplant candidates now generally wait longer before transplantation than in earlier eras, in many cases waiting a year or longer. The increased waiting times have precipitated a rise in the number of patients who deteriorate and therefore require hospitalization or mechanical circulatory support before transplantation.2 Because heart transplantation depends on a limited supply of donor hearts, individuals listed as candidates for transplantation should be those who are most likely to benefit.

Those involved in cardiac intensive care need a sound understanding of issues surrounding cardiac transplantation. In addition to being expert at managing acute decompensated heart failure, cardiac intensivists must be able to: (1) determine which patients have stage D heart failure; (2) determine which stage D heart failure patients are potentially suitable heart transplant candidates; (3) manage critically ill transplant candidates, escalating therapies from intravenous diuretics, to intravenous inotropes and vasodilators, and finally to mechanical circulatory support, as required; (4) manage or assist in managing recipients immediately following heart transplantation; and (5) evaluate and manage longer-term posttransplant complications that necessitate cardiac intensive care. Moreover, a strong collaborative approach with a transplant cardiologist is vital for overall patient care. Specifically, pretransplant evaluation and care, early identification of patients having posttransplant comorbidities, including hemodynamically compromising cardiac allograft rejection, atypical infections, immunosuppressive therapy and its potential adverse effects, among others, must be seamlessly coordinated.3

Stage D Identification and Candidate Selection Criteria

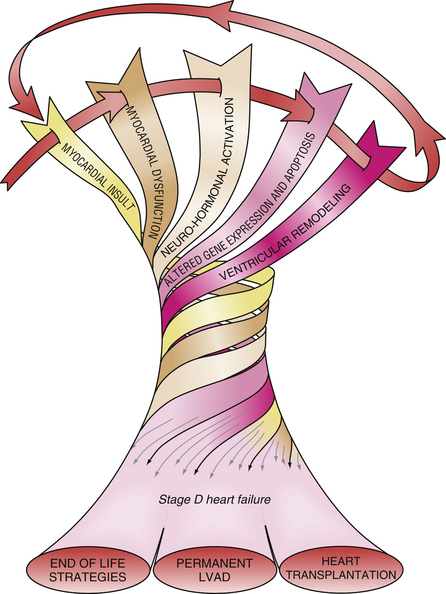

Stage D heart failure patients have end-stage disease and a short life expectancy, typically only 50% at 1 to 2 years. Medications that previously were beneficial are no longer well tolerated and hospitalizations are frequent. As shown in Figure 48-2, therapeutic options are limited to end-of-life strategies, transplantation, or support with a left ventricular assist device intended as permanent or “destination” therapy.3,4

Once a stage D heart failure patient is identified, transplant candidacy should be determined. Careful candidate selection rations the limited supply of donor hearts to patients most likely to benefit from transplantation. The question, “Is this patient a suitable heart transplant candidate?” must therefore be asked and answered. The evaluation is comprehensive, including the elements outlined in Table 48-1. However, a thorough evaluation is either unnecessary or could be delayed, if indications are not met (Table 48-2) or if risks are inordinately high (Table 48-3). A history of severe heart failure or suboptimally treated heart failure is, per se, an insufficient indication for heart transplantation. These patients may actually still have stage C heart failure.3

Table 48–1 Evaluation of Potential Cardiac Transplant Candidates

| Detailed medical history and thorough physical examination |

| Laboratory evaluation: |

| CBC |

| Renal function tests (BUN/creatinine, creatinine clearance, GFR) |

| Liver function tests (alkaline phosphatase, bilirubin, albumin, transaminases) |

| Coagulation (prothrombin time, partial thromboplastin time) |

| Urinalysis |

| ABO blood type and antibody screen |

| Serologies for hepatitis A, B, C; HIV; cytomegalovirus; Epstein-Barr virus; herpes simplex virus I, II; Toxoplasma gondii; syphilis; skin test for tuberculosis with controls |

| Right heart catheterization |

| Left heart catheterization/coronary angiography (if indicated) |

| Echocardiogram (or other form of ventriculography, if indicated) |

| ECG and/chest x-ray |

| Carotid ultrasound (if indicated) |

| Pulmonary function tests |

Exercise testing with measured oxygen consumption  |

| Histocompatibility leukocyte antigen (HLA) typing/panel reactive antibody (PRA) |

| Psychosocial/financial consultation |

CBC, complete blood count; BUN, blood urea nitrogen; GFR, glomerular filtration rate; HIV, Human immunodeficiency virus; ECG, electrocardiogram.

Table 48–2 Indications for Heart Transplantation

| Heart failure requiring respirator, intra-aortic balloon pump, or ventricular assist device |

| Heart failure requiring continuous inotropic support |

| Refractory NYHA Class III or IV symptoms despite maximal medical and surgical therapy |

| Estimated 1-year survival without transplantation ≤ 50% |

Peak oxygen consumption  ≤ 12-14 mL/kg/min or marked serial decline over time ≤ 12-14 mL/kg/min or marked serial decline over time |

| Hypertrophic or restrictive cardiomyopathy with NYHA Class IIIb-IV symptoms |

| Refractory angina pectoris despite optimal medical, surgical, and/or interventional therapy |

| Recurrent life-threatening ventricular arrhythmias despite optimal medical, electrophysiologic, device, and surgical therapy |

| Cardiac tumors with low likelihood of metastasis |

| Medically refractory NYHA Class III-IV heart failure due to surgically untreatable complex congenital heart disease |

| Hypoplastic left heart syndrome |

NYHA, New York Heart Association.

| Age≥ 65 years |

| Diabetes mellitus if: |

| End-organ dysfunction (retinopathy, nephropathy, neuropathy) |

| Poor glycemic control despite aggressive medical and dietary therapy |

| Intractable pulmonary hypertension despite maximal vasodilators/inotropes |

| Transpulmonary gradient ≥ 15 to 20 mm Hg |

| PVR ≥ 4-6 Wood units |

| Extensive peripheral vascular disease |

| Significant cerebrovascular disease |

| Marked renal impairment |

| Serum creatinine >2.5 mg/dL |

| Creatinine clearance <50 mL/min |

| Marked hepatic impairment |

| Serum bilirubin >2.0 mg/dL |

| Serum transaminases > twice upper limits of normal |

| Elevated prothrombin time without anticoagulation |

| Significant pulmonary dysfunction |

| Active infection |

| Malignancy/history of malignancy without evidence of cure |

| Obesity: BMI >40 kg/m2 |

| Active psychiatric disorders |

| Inadequate financial resources/social support |

PVR, pulmonary vascular resistance; BMI, body mass index.

Specific selection criteria vary among transplant centers, but several general patient characteristics and factors are common among the majority of programs. Table 48-2 lists the indications generally used when a patient is considered for cardiac transplantation. Left ventricular function parallels the prognosis in severe cardiac failure. Survival dwindles as objective measures of left ventricular function decline. However, a low left ventricular ejection fraction alone is an inadequate indication for heart transplantation. Additional objective evidence of severe cardiac impairment is needed. For example, objective determinations of exercise capacity and oxygen consumption have proven useful in determining the degree of cardiac dysfunction and prognosis.5,6 A peak oxygen consumption ( ) of ≤14 mL/min/kg or ≤ 12 mL/min/kg in patients on β-adrenergic receptor antagonists7 indicates a degree of cardiac dysfunction sufficient to warrant consideration for transplantation. Alternatively, a peak

) of ≤14 mL/min/kg or ≤ 12 mL/min/kg in patients on β-adrenergic receptor antagonists7 indicates a degree of cardiac dysfunction sufficient to warrant consideration for transplantation. Alternatively, a peak  of less than 50% of predicted for age and gender can prompt consideration for cardiac transplantation evaluation.6 Serial measurements provide a way to gauge the effectiveness of current therapies and the progression of disease during the waiting period. It is recommended that peak

of less than 50% of predicted for age and gender can prompt consideration for cardiac transplantation evaluation.6 Serial measurements provide a way to gauge the effectiveness of current therapies and the progression of disease during the waiting period. It is recommended that peak  values be adjusted for patient age, gender, and weight.

values be adjusted for patient age, gender, and weight.

Subjective measures also influence the decision to proceed with cardiac transplantation as part of the management of chronic heart failure. An unsatisfactory quality of life and intolerable symptoms of cardiac disease despite maximal medical therapy are key factors to consider. Although refractory heart failure is the principal reason by far for considering cardiac transplantation, numerous other cardiac disease entities also have been proposed as bases for transplantation, as shown in Table 48-2. Whatever the cause underlying the cardiac impairment, a predicted survival of 50% at 1 to 2 years without cardiac transplantation warrants proceeding with transplant evaluation and placement on the waiting list while conventional therapies are continued.

Once the degree of cardiac impairment meets one of the preceding indications, a comprehensive evaluation is performed to detect conditions that decrease the likelihood of a favorable posttransplant outcome. Table 48-3 delineates many of the risk factors that help determine the safety and appropriateness of transplantation for stage D heart failure. Most of these are no longer viewed as contraindications to cardiac transplantation, but risk factors only. In fact, while not routinely advisable, most have been successfully overcome in carefully selected individual patients.

Age

Most centers set a specific age limit beyond which patients are not considered as potential candidates.8,9 Although survival in older patients has modestly improved in recent years, the registry of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation (ISHLT) indicates that older age remains a continuous predictor of 1-year and 5-year mortality following transplantation.2 Enthusiasm for transplanting patients older than 65 to 70 years of age is further tempered by the scarcity of donor hearts and the higher prevalence of coexistent medical illnesses in the older patient population. Although not a universally accepted practice, alternate waiting lists have been used for candidates over the age of 70 years. Transplantation then proceeds using donor hearts that otherwise would not have been used.

Diabetes Mellitus

Some patients with diabetes mellitus and no, or minimal end-organ damage have been transplanted with excellent short and intermediate outcomes. Yet diabetes still poses additional challenges posttransplant. Patients with less than optimal glycemic control often worsen considerably with the use of corticosteroids following transplantation. Insulin may be required for a time postoperatively even in those patients previously well controlled with dietary measures or oral hypoglycemic agents. Evidence of end-organ damage before transplantation may identify patients with more advanced diabetes and define a subset of diabetics likely to suffer considerable deterioration of diabetes following the procedure. In general, those patients with manifestations of proliferative retinopathy, nephropathy, neuropathy, or peripheral vascular complications secondary to their diabetes are considered higher-risk candidates for cardiac transplantation. The most recent ISHLT registry indicates a significant 1-year mortality risk in insulin-dependent diabetic recipients.2

Pulmonary Hypertension

Elevated pulmonary arterial pressures and pulmonary vascular resistance are common in patients with the degree of cardiac failure that compels consideration of cardiac transplantation. However, excessive elevations of pulmonary vascular resistance identify patients at high risk following the transplant procedure. Several studies have shown that marked pulmonary hypertension is associated with increased early mortality secondary to right ventricular failure during the perioperative period.10,11,12 During the initial evaluation of a patient under consideration, right heart catheterization and direct measurement of the hemodynamic parameters is performed. A pulmonary artery systolic pressure of 50 mm Hg, a transpulmonary gradient of 15 mm Hg, or a pulmonary vascular resistance of 3 Wood units should prompt a challenge with a vasodilator and/or an inotropic agent. If these parameters can be corrected during initial hemodynamic measurement (e.g., with the administration of intravenous nitroprusside or inotropic agent), then it can safely be assumed that these abnormalities are secondary to the marked degree of cardiac dysfunction. Alternatively, patients whose initial hemodynamic status precludes consideration may be re-evaluated after a period of augmented medical therapy, particularly if earlier therapies had not yet been maximized. Patients with persistent pulmonary arterial hypertension despite a trial of different medical therapies may be considered for mechanical circulatory support to decrease left ventricular filling pressures over a period of months and assessing whether pulmonary pressures have become acceptable for heart transplantation. Serial measurements of hemodynamic status are routinely performed during the waiting period, not only to monitor the effectiveness of current medical therapies, but also to allow intervention if worsening pulmonary hypertension and elevated pulmonary vascular resistance are detected. On occasion, it is necessary to hospitalize patients and administer continuous intravenous vasodilators or inotropes to avoid the development of irreversible pulmonary hypertension, which would prohibit cardiac transplantation. In some instances, using a larger donor heart than would normally be required based upon the recipient body surface area may offer increased right ventricular work capacity to overcome the elevated pulmonary vascular resistance. Otherwise, only a combined heart-lung transplantation or heterotopic heart transplantation to surmount excessive pulmonary hypertension would be feasible.13 In this age of increased use and better timing of mechanical circulatory support, these latter options are seldom used.

Peripheral Vascular Disease and Cerebrovascular Disease

Symptomatic peripheral vascular disease and significant cerebrovascular disease pose additional hazards following transplantation. Severe peripheral vascular obstruction can occasionally preclude the use of an intra-aortic balloon pump and may impede the functional capacity of the transplant recipient in the long run. The risk of stroke and lower extremity ischemia following transplantation should be assessed. As part of the routine pretransplant evaluation, carotid Doppler ultrasound should be performed in patients with coronary artery disease or in patients older than 40 to 50 years of age. If significant carotid occlusive disease is identified, surgical correction should be strongly considered before transplantation.14

Infection

However, a patient who tests positive for cytomegalovirus, Toxoplasma gondii, Epstein-Barr virus, or who has a positive tuberculin skin test is not excluded from consideration; rather the patient requires additional care and treatment after immunosuppression is begun. A thorough dental examination, with appropriate treatment, and screening for hepatitis B and C and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), are warranted. Positive testing for hepatitis B or C does not necessarily preclude transplant consideration but requires additional evaluation. Furthermore, even a patient who is HIV positive without a history of an AIDS-defining illness may not be excluded from transplant evaluation. These patients should be evaluated on an individual basis.15

Malignancy

Transplantation of a patient with a malignancy without evidence of cure is extraordinarily risky. Despite some reports indicating moderate short-term success in patients with malignancies undergoing successful transplantation,16 consideration should be given only to those patients who have a suitable response to medical or surgical therapy, have a low malignancy recurrence rate, and have been disease-free for a sufficient period of time following the initial diagnosis.

Obesity

At most transplant centers, class III or morbid obesity (body mass index [BMI] ≥ 40 kg/m2) has been considered a relative contraindication. This degree of obesity may predispose to poor wound healing, higher infection risk, and worse functional recovery after transplantation. Obesity has also been associated with increased cardiac allograft vasculopathy and worse survival after transplant.17,18 In addition, difficulty is encountered identifying a suitable donor heart, which can accommodate the size match required for a morbidly obese transplant candidate.