58 Bradyarrhythmias

• Look at the patient first and then the heart rhythm. A “slow heart rate” is relative to the patient’s age, clinical condition, and comorbid conditions.

• Determine whether the cause is extrinsic or intrinsic to the conduction system.

• Assess the functionality of the key elements of the conduction system: sinoatrial and atrioventricular nodes and the infranodal conduction system.

• Know the vascular supply of the conduction system to determine the significance of bradyarrhythmias and conduction blocks in the setting of acute myocardial infarction.

• Identify risk for failure of the conduction system and the “backup”; for example, a stable escape rhythm, atropine, or a pacemaker.

Epidemiology

Bradycardia is a frequent finding in clinical practice, and its significance is dependent on the underlying cause and clinical effects. The baseline heart rate in an individual patient is determined predominantly by the balance between the parasympathetic and sympathetic nervous systems, and a “normal” heart rate has been defined arbitrarily as 60 to 100 beats/min at rest. The heart rate will vary depending on age, physical condition, and time of observation. Normal ranges for a healthy asymptomatic individual will vary from 46 to 93 beats/min in men and 51 to 95 beats/min in women during the day to rates as low as 40 beats/min at night.1 The heart rate should fluctuate with respiration, the Valsalva maneuver, and other vagal influences confirming normal autonomic control of the sinus node. Bradycardia is a frequent finding in trained athletes, in whom heart rates lower than 40 beats/min are often observed at rest.2 Bradycardias of clinical significance increase in frequency with age and in the setting of illnesses or medications affecting the heart and its conduction system.

Pathophysiology

Extrinsic Causes

Clues to an extrinsic cause of a bradyarrhythmia are a history of a new cardioactive medication, conditions that activate vagal tone, and extreme electrolyte imbalances, specifically potassium (Table 58.1). The associated rhythms are typically those that are due to dysfunction of the sinus or atrioventricular (AV) node:

Table 58.1 Extrinsic Causes of Bradyarrhythmias

| COMMON | UNCOMMON | |

|---|---|---|

| Drugs | ||

| Situational reflex | ||

| Metabolic | ||

| Ischemia and infarction | — | |

| Other | — |

From Ford M. Clinical toxicology. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2001. pp. 23-5.

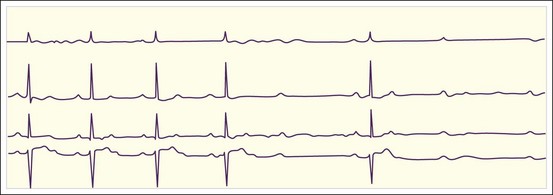

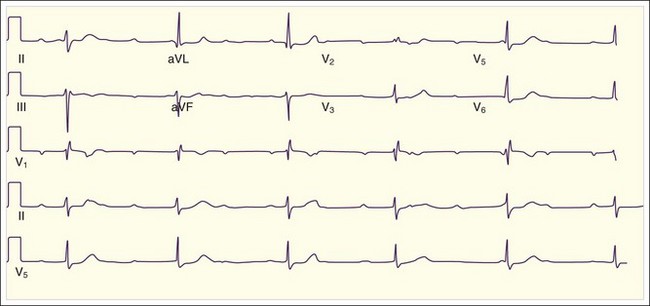

Fig. 58.2 Sinus bradycardia with a ventricular response rate of 59 beats/min.

There is a P wave for every QRS complex and normal PR intervals.

Intrinsic Causes

Certain conditions result in failure of elements of the conduction system because of aging, ischemia or infarction, surgical trauma, or infiltration (Table 58.2). The latter cause encompasses a large group of conditions that include infectious and rheumatologic diseases.3–5 The associated rhythms are typically those that indicate failure of one element of the conduction system rather than failure to generate a rhythm:

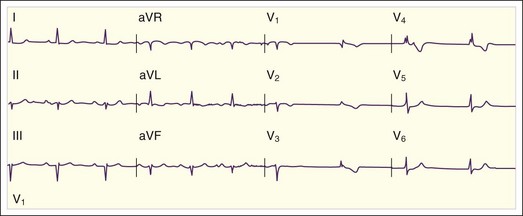

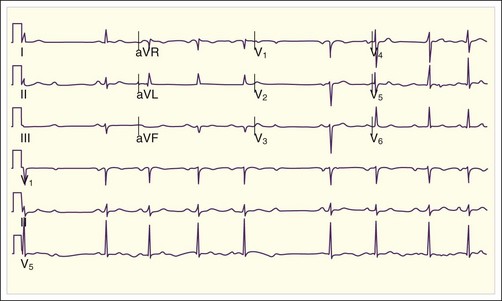

• Second-degree AV block (either type I or type II) (Fig. 58-5; also see Fig. 58.4)

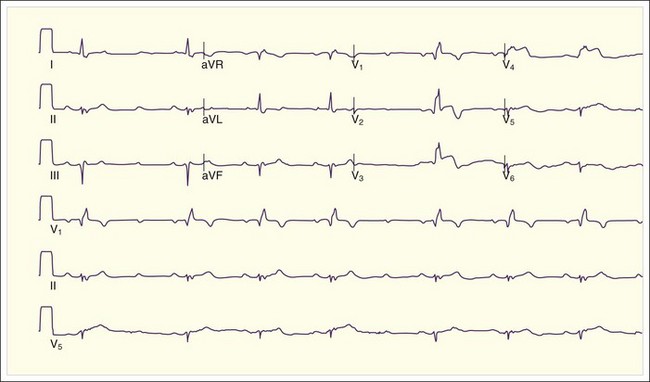

• Third-degree heart block (Fig. 58.6)

• Associated fascicular or bundle branch blocks (see Fig. 58.5)

Table 58.2 Intrinsic Causes of Bradyarrhythmias

| Ischemia and infarction | |

| Infection | |

| Malignancy | |

| Rheumatologic | |

| Other |

MI, Myocardial infarction.

Relative Bradycardia

Relative bradycardia is the presence of a heart rate that is inappropriately slow for the clinical findings. Though often caused by coexisting beta-blocker therapy or age-related blunting of sinus node automaticity, it is also a diagnostic feature of a number of infectious disorders. Relative bradycardia is most useful in differentiating infectious diseases that resemble each other; for example, legionnaires’ disease from Mycoplasma pneumonia and psittacosis or Q fever from tularemia pneumonia.3