Bowel Obstruction

Vishal Bansal

Raul Coimbra

Introduction

Bowel obstruction is a common indication for surgical consultation. The source of obstruction may be within the lumen of the bowel itself (i.e., neoplasm), the result of pathology external to the bowel (i.e., adhesions), or secondary to anatomic abnormalities (i.e., hernia). Although symptoms may be similar, it is important to establish whether the small or large intestine is obstructed since the differential diagnosis of bowel obstruction, management, and treatment vary according to anatomic location. A careful H&P, coupled with select radiologic imaging is often sufficient to distinguish large bowel from small bowel obstruction.

I. Definitions

Partial bowel obstruction—bowel lumen is narrowed but permits passage of some air and fluid as evidenced by flatus or distal gas radiographically.

Complete bowel obstruction—lumen is totally occluded and does not allow passage of air or fluid as evidenced by a lack of flatus or distal gas radiographically.

Simple bowel obstruction—lumen is partially or completely obstructed without compromise of intestinal blood flow.

Complicated bowel obstruction—blood flow to a portion of bowel is compromised, either from increased intraluminal pressure interrupting venous outflow, or interruption of mesenteric flow by twisting or entrapment.

Closed loop obstruction—outflow of bowel contents obstructed at both ends of bowel preventing prograde and retrograde decompression which leads to more rapid distension and increased likelihood of bowel ischemia.

Volvulus—a segment of intestine twists about its mesentery.

II. Initial Evaluation

Patients who present with bowel obstruction typically require intravascular volume repletion. Depending on the duration of symptoms and level of obstruction, patients will present with severe volume depletion. Concurrent with diagnostic evaluation, early fluid resuscitation should be instituted.

Initial resuscitation begins with isotonic fluids.

The frequently present potassium deficiency is corrected with potassium chloride after restoration of intravascular volume, usually noted by the return of adequate urine output.

Treatment with sodium bicarbonate is only a temporizing measure that should be avoided.

Adjuncts to resuscitation, including nasogastric decompression and bladder catheter placement, are beneficial in all but the mildest cases of bowel obstruction. Invasive monitoring may be indicated in patients with cardiac, pulmonary, or renal insufficiency.

Evaluation for the possibility of a complicated obstruction should take first priority in the patient with bowel obstruction. These patients require few if any imaging studies and treatment centers on rapid resuscitation and prompt exploratory laparotomy. Although there are no specific findings or diagnostic tests which confirm or exclude strangulating obstruction, the following findings are worrisome for this diagnosis and should prompt consideration for urgent intervention.

Physical findings—fever, severe continuous abdominal pain, tachycardia, rebound tenderness, and abdominal rigidity.

Laboratory findings—acidosis, leukocytosis.

Radiologic findings of complicated obstruction-–Pneumatosis intestinalis, portal venous gas, or pneumoperitoneum suggest that necrosis has already occurred. Thumbprinting, loss of mucosal pattern, and bowel wall gas are also ominous findings that usually warrant surgical exploration.

III. Small Bowel Obstruction

Etiology

Adhesions. Post-operative adhesions account for 70% of SBOs. A history of a previous intra-abdominal operation is suggestive. A history of other pathology (without previous abdominal operation) such as perforated peptic ulcer disease, diverticulitis, pelvic inflammatory disease, or a history of radiation may cause peritoneal scarring and omental adhesions which serve as a nidus for SBO.

Hernias. Incarcerated hernias are the second most common etiology of SBO; and the most common cause in patients without previous abdominal surgery. Inguinal, umbilical, ventral, or femoral hernias are readily identifiable on physical examination. Computed tomography (CT) may help diagnose partial incarcerations (Spigelian or Richter’s hernia), paraesophageal, or internal hernial defects.

Neoplasms. Neoplasms (most often benign in small bowel) can serve as an obstructing lesion or as an anatomic lead point for an intussusception. Suspicion for a neoplasm is best detected on CT, small bowel follow through or occasionally capsule endoscopy.

Crohn’s disease. A known history of inflammatory bowel disease coupled with CT or endoscopic imaging is usually diagnostic. Etiology may be from acute exacerbation, chronic stricture, intra-abdominal abscess, or enteric fistula.

Intussusception. A viral prodrome often with mesenteric lymphadenopathy, Meckel’s diverticulum, or intestinal neoplasm may lead to intussusception. CT shows a “target” sign representing the proximal small bowel intussusceptum telescoping within the intussuscipiens.

Gallstone ileus. Commonly occurs in elderly and infirmed patients, more commonly female, with undiagnosed chronic cholecystitis causing a cholo-enteric fistula. Plain abdominal x-rays may reveal a stone in the right lower quadrant. CT may demonstrate pneumobilia or an obstructing gallstone at the ileocecal valve.

Foreign bodies. Foreign objects and migrating bezoars are most often seen in the pediatric or psychiatric population. History and imaging is diagnostic.

Presentation and initial assessment. The most important determination to make during the initial assessment is if the patient has findings consistent with bowel strangulation, gangrenous/ischemic bowel, or peritonitis. Patients with these findings should undergo immediate exploration without further diagnostic modalities.

The clinical presentation is an important clue to etiology and management. Patients usually present with colicky abdominal pain, distension, nausea, and vomiting with obstipation. In proximal obstruction, vomiting can be severe and patients may not be distended. Often, especially with adhesive disease, patients have had previous similar episodes.

History should address previous operative procedures or abdominal pathology given the likelihood of adhesions as the cause. In the absence of this history, adhesive disease is not likely and other etiologies must be considered. Other past medical history such as hernia, Crohn’s disease, history of radiation, and recent viral illness should be elicited. The adult patient presenting with a bowel obstruction in the absence of previous abdominal surgery or hernia on examination generally has an anatomic cause for the obstruction which will require surgery.

Physical examination should be focused to detect findings of peritonitis or devitalized small bowel. Additionally, observe previous surgical scars or hernias. No other diagnostic modality should be undertaken if peritonitis has been documented; these patients should be explored expeditiously. In patients without peritoneal signs, degree of distension and severity or absence of abdominal pain is

important to document and follow serially. The patient with complete bowel obstruction or closed loop obstruction should undergo early operation. Patients with incomplete bowel obstruction without signs of peritonitis may be admitted for serial examination.

Laboratory abnormalities. Most laboratory values are non-specific and often normal, even in the face of a closed loop obstruction or bowel ischemia. A complete blood count (CBC) and an electrolyte panel may be helpful in management.

CBC. Follow the white blood cell count in patients managed non-operatively. An initially high or rising leukocytosis should be cause of concern for ischemic bowel and exploration should be considered. Importantly, a normal CBC does not preclude bowel ischemia.

Electrolyte panel. Electrolyte abnormalities may be significant, especially hypokalemia, in proximal SBO with intense vomiting. A rising serum creatinine may be a result of dehydration.

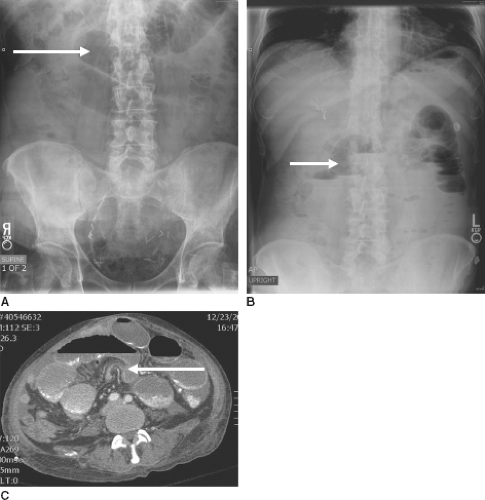

Radiographic evaluation. Radiographic evaluation may help delineate the anatomic location and degree of obstruction. An acute abdominal x-ray (AXR) may be the only study required, especially if adhesive disease is the etiology of the SBO. Abdominal CT often may help direct management.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree