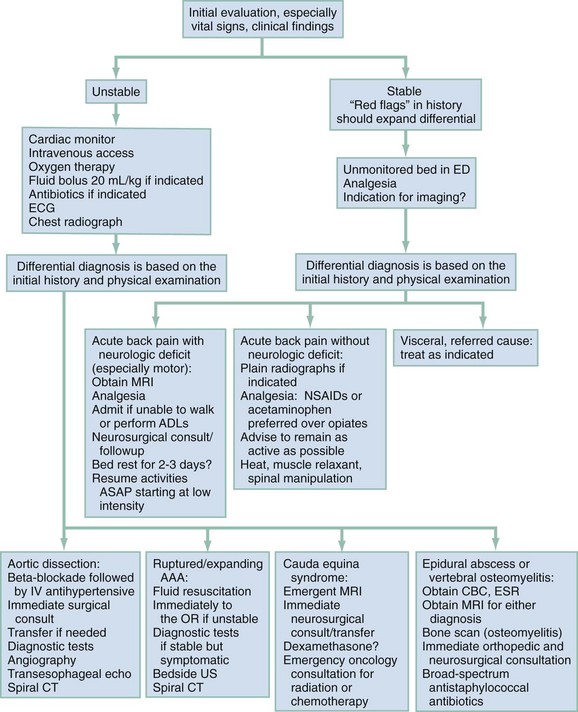

Chapter 35 Back pain is a common symptom causing patients to seek care in the emergency department (ED). It accounts for 2.3% of all physician visits,1 and 84% of the adult population have experienced low back pain in their lifetime.2 Forty-nine percent have experienced low back pain in the last 6 months,2 and 26% in the last 3 months.1 Total costs of low back pain in the United States exceed $100 billion per year.3 Although mechanical or nonspecific low back is the most common cause, the differential diagnosis includes several life-threatening and disabling conditions (Box 35-1). Developing a systematic approach that screens all the potential causes of back pain is the key to accurate clinical decision-making. Ninety-seven percent of patients visiting a physician for evaluation of acute low back pain, defined as lasting less than 6 weeks, are ultimately diagnosed with mechanical or nonspecific low back pain.4 The vast majority of these are strain and degenerative in origin, but a few percent have herniated disk, spinal stenosis, fracture, and congenital disorders. Seventy-two percent will have completely recovered at 1 year.5 For those with chronic back pain, defined as lasting longer than 3 months, persistence or a recurrence within 12 months is very common.6 About 1% of all patients with back pain have true sciatica.6 Back pain is the second most common cause of lost time in the workplace and an enormous source of health care expenditures and lost productivity.7,8 The prevalence of chronic low back pain is rising.9 Before these common mechanical causes are considered, several emergent diagnoses should be excluded, including aortic dissection, abdominal aortic aneurysm, cauda equina syndrome, epidural abscess, osteomyelitis, and tumor. The presence of certain symptoms (Box 35-2) should prompt a more thorough examination of these possibilities. Visceral causes constitute about 2% of the diagnoses in patients with back pain.4 Aortic dissection is a rare but catastrophic event, with mortality rates exceeding 90% if it is not diagnosed. Cauda equina syndrome (bilateral leg pain and weakness, urinary retention with overflow incontinence, fecal incontinence or decreased rectal tone, and “saddle anesthesia”) is a rare but rapidly progressive disabling complication usually caused by a large central herniated disk and less often by tumor or infection. Epidural abscess and vertebral osteomyelitis constitute 0.01% of the diagnoses in patients complaining primarily of back pain.4 Spinal carcinoma is uncommon (0.7%) in the general population with back pain,4 but in cancer patients, 80% who report back pain have spinal metastases. Metastasis to bone is seen commonly in breast, lung, prostate, kidney, and thyroid carcinomas. Other tumors include primary bone cancers, multiple myeloma, lymphoma, and retroperitoneal tumors. Inflammatory arthritis is the diagnosis for 0.3% of patients with back pain.4 The gelatinous nucleus pulposus is surrounded by the tough anulus fibrosus. The anulus thins posteriorly, creating the opportunity for the nucleus pulposus to herniate. This varies from bulging to protrusion to extrusion to sequestration. Ninety-five percent of clinically significant herniations occur at the L4-5 and L5-S1 disk spaces, causing radicular pain in the L5 and S1 dermatomes.4 Involvement of the L5 nerve root manifests with decreased sensation in the first web space, weakness with extension of the great toe, but normal reflexes. An S1 radiculopathy is characterized by diminished sensation of the lateral foot and small toe, impaired plantar flexion, and a decreased or absent ankle jerk. Anatomic disk bulging (52-81%) and annular tears with focal disk protrusion (32-67%) usually do not cause symptoms, whereas disk extrusion (0-18%) is usually symptomatic.10–13 Serial magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies show that two thirds of herniated disks regress or resolve over 6 months.4 Three fourths of patients’ symptoms improve within 6 weeks. In the absence of suspected cauda equina syndrome, computed tomography (CT) or MRI is not indicated in the evaluation of patients with suspected disk herniation. Many patients with a herniated disk improve over time, and many asymptomatic patients have radiographic findings, so imaging is not helpful and may be misleading. This natural resolution of symptoms in disk disease is in contrast to spinal stenosis, which tends to remain the same or worsen over time.4 The ligamentum flavum can thicken with age and along with degenerative changes contributes to spinal stenosis. The emergency physician first evaluates for potential life-threatening and disabling causes of back pain, including thoracic aortic dissection, ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm, epidural abscess or compressive mass, spinal column injury with cord or root compression, and cauda equina syndrome. An accurate history and physical examination guide the investigation of possible more serious underlying pathologic process (see Boxes 35-1 and 35-2).4 Laboratory tests and imaging are needed in some cases, but it is usually possible to rule out significant pathology without recourse to extensive testing. If the initial history and physical examination identify any suggestion of serious disease, rapid stabilization measures should ensue consistent with the cause of concern (Fig. 35-1). Management of aortic dissection, ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm, and spinal cord and column injuries are covered in other chapters. If epidural abscess, hematoma, or cauda equina syndrome is suspected, emergent MRI is obtained, with neurosurgical consultation when indicated by the results of the scan. For epidural abscess, blood cultures are obtained, followed by intravenous administration of antibiotics against Staphylococcus aureus. For cauda equina syndrome,14 an urgent neurosurgical consultation is required. Once urinary retention occurs, the prognosis worsens and emergent spinal decompression is indicated. Although the evidence supporting steroid use is conflicting, dexamethasone is commonly used with the hope of decreasing compression from inflammation or to shrink tumor mass. For all patients with significant pain, including patients with “benign” causes for back pain, effective analgesia should be provided early in the evaluation. The history and physical examination should help sort patients into unstable and stable categories (see Fig 35-1). Certain findings will guide additional workup to discover causes for patients with neurologic deficits, and more serious spinal or visceral sources (see Box 35-2). History of Present Illness.: The history helps to localize pain to the most likely structure and mechanism. The following questions are useful in differentiating between mechanical and nonmechanical causes and between unstable and stable patients and help guide appropriate management. Where is the pain?: The patient is asked to point with one finger to the one spot where it hurts the most. Does the pain radiate, and if so, specifically where? Does the pain conform to a specific dermatomal area? Radicular pain, particularly extending below the knee in a dermatomal distribution, implies nerve root involvement. Sciatica radiates below the knees, causing focal motor and sensory loss. It worsens with bending, sitting, coughing, sneezing, and straining. Pain mainly in the paralumbar musculature without dermatomal radiculopathy implies nonspecific low back pain. Any associated chest or abdominal pain may indicate a visceral cause. Flank location implies a renal or retroperitoneal origin, and a higher location can be from the chest or pleura.

Back Pain

Perspective

Epidemiology

Pathophysiology

Diagnostic Approach

Rapid Assessment and Stabilization

Pivotal Findings

History

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Back Pain

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue