INTRODUCTION

Use local and regional anesthetic techniques when the equipment, supplies, and experienced personnel to give deep sedation or general anesthesia are unavailable. This is frequently the case during initial disaster responses and in limited-resource settings. As one experienced anesthesiologist wrote, “We must assume that supplies of compressed gases will soon run out and replacements will be unobtainable. This leaves us with local techniques, spinal and epidural analgesia, all of which can be given by the surgeon in the absence of a trained anesthetist.”1

TOPICAL ANESTHETICS

Topical anesthetics are slowly absorbed through normal skin. However, they are rapidly absorbed through the mucosa, as well as through abraded, burned, and denuded skin. When using topical anesthetics in these areas—especially if used in the tracheobronchial tree—the maximum dose should be considerably less than that used for infiltration.2,3 Tetracaine, for example, produces higher blood levels at 5 minutes with mucosal application than with subcutaneous infiltration.4 When used in dentistry, topical anesthetics generally anesthetize only the outer 1 to 3 mm of mucosa.5 That, however, makes them effective to dull the pain of intraoral injections.

Good topical anesthetics include lidocaine (lignocaine), cocaine, and tetracaine. Some anesthetics, such as procaine and mepivacaine, are not effective topically due to poor mucous membrane penetration.3

Lidocaine (amide) (2% to 10% [20 to 100 mg/mL]) has a peak anesthetic effect in from 2 to 5 minutes. Its maximum safe total dose (without epinephrine) in a healthy 70-kg adult is ~250 mg and it is 3 mg/kg in children. Anesthetic effect lasts 30 to 45 minutes.2,3 Lidocaine gel 4% can be made by adding 2 mL of 2% lidocaine without epinephrine to 1 mL of a water-soluble jelly (e.g., K-Y). This gel works well, if placed under an occlusive dressing, to ease the pain of herpes zoster and other skin lesions.

Bupivacaine (amide) (0.25% to 0.5% [2.5 to 5 mg/mL]) has a peak anesthetic effect in 2 to 5 minutes. Its maximum safe total dose in a healthy 70-kg adult is 400 mg/24 hours; it is 2 mg/kg in children, although it is not officially recommended for use in children <12 years old. Similarly, it is not recommended as a spinal anesthetic in those <12 years old. Anesthetic effect lasts 4 to 8 hours.

Cocaine (ester) (4% [40 mg/mL] is the usual concentration) has a unique vasoconstricting effect. It reaches peak anesthetic effect in 2 to 5 minutes. However, it is addictive. The maximum safe total dose in a healthy 70-kg adult is 200 mg (2 to 3 mg/kg) and it is 2 mg/kg in children. The anesthetic effect lasts from 30 to 45 minutes.2,3 Staying within the maximum adult dose is easy if the standard package of 4 mL of the 4% solution is used. While making your own topical solution with cocaine obtained from noncommercial vendors may seem logical in an emergency, the problem is that neither the strength nor the purity of the ingredient is known.

Tetracaine (ester) (0.5% [5 mg/mL] is the usual concentration) has a peak anesthetic effect in 3 to 8 minutes. The maximum safe total dose in a healthy 70-kg adult is 50 mg and it is 0.75 mg/kg in children. Its anesthetic effect lasts 30 to 60 minutes.2,3

Local anesthetics can produce allergic reactions, tissue damage, and systemic toxicity. Allergic reactions are most common with the ester preparations (e.g., procaine, tetracaine). There is no cross-reactivity between the esters and amides (e.g., lidocaine, bupivacaine, mepivacaine). Allergic reactions to local anesthetics are rare, with most reported allergies not representing actual allergic reactions. Local tissue neurotoxicity can also occur, but it is rare.

Usually associated with inadvertent intravenous (IV) or intra-arterial injections, systemic toxicity is the most common and significant problem associated with local anesthetic use. Mental status changes may be the only resulting sign or symptom that occurs before seizures begin. Classically, the progression of systemic toxicity is tongue numbness, light-headedness, visual disturbances, muscular twitching, unconsciousness, and seizures. Patients who receive local anesthetics while sedated may have muscular twitching as the only sign before seizures. The treatment is to stop local anesthetic use, manage the airway, control the seizures, and support the patient until the central nervous system (CNS) effects of the drug wear off. The local anesthetics themselves do not cause CNS damage. Rather, the damage stems from hypoxia during the seizure and the associated coma.6

Many topical oral anesthetic formulations ease the pain from mucosal lesions. Young children’s inability to spit after gargling is a primary reason that plain oral lidocaine (usually 2%, or 20 mg/mL) is rarely used in this age group, although it is generally safe and appropriate in older children. In very young children, even a single dose of swallowed viscous lidocaine may cause toxicity and death (toxic dose is 6 mg/kg).7 While it may reduce the pain, viscous lidocaine does not improve oral intake in children with painful infectious mouth ulcers.8

A topical agent that seems to work well, and that uses commonly available ingredients, is a mixture of equal parts of 2% viscous lidocaine, diphenhydramine elixir, and Maalox or Kaopectate (as a binder).2 Swish for 1 to 2 minutes and spit. This is especially useful in older children with oral lesions that prevent the child from drinking or eating.

Lidocaine for injection can be nebulized as an effective topical mucosal anesthetic. Some patients experience a strong bitter taste when lidocaine is administered this way; however, the taste is usually transient and this should not prevent the patient from receiving the medication. (Angela M. Plewa, PharmD. Personal communication, April 8, 2008.) To use it, the best course is to dilute it to a 0.5% solution so that the maximum safe dose is not exceeded.

Anesthetic creams are useful to reduce pain before suturing, phlebotomy, or IV insertions. They are primarily used in children.

LET (lidocaine 4%, epinephrine 0.1%, and tetracaine 0.5%), which can be compounded locally, can be used to anesthetize small lacerations on the face and scalp before repair. This works particularly well in children and has less toxicity than TAC (tetracaine 0.25% to 0.5%, adrenaline 0.025% to 0.05%, and cocaine 4% to 11.8%), which was previously widely used. In an emergency, either works well. They both work in about 75% to 90% of patients. An older formulation mixing epinephrine in cocaine, termed “cocaine mud,” had a very high complication rate; don’t use it.

For LET solution, mix 100 mL 20% lidocaine HCl, 50 mL 2.25% racemic epinephrine (HCl salt), 125 mL 2% tetracaine HCl, 315 mg sodium metabisulfite, and 225 mL water. Make the gel by mixing the solution with methylcellulose.

The LET formula is effective both in a solution and as a gel. For the solution, paint it onto the wound edges with a cotton-tipped applicator. Then apply a cotton ball saturated with the solution to the wound. In about 20 minutes, the wound appears blanched and is ready to suture. Apply the gel to both the wound edges and the wound with a cotton-tipped applicator. As with the solution, the wound edges look blanched and the wound is ready to suture in about 20 minutes. Remove the gel before suturing.9

Anesthetic patches effectively anesthetize the skin and underlying area of painful lesions. They can be used for herpetic, post-herpetic, and rib fracture pain. They only have a placebo effect when applied for joint pain.

To improvise a topical anesthetic patch for abrasions and wounds, soak gauze with a mixture of injectable lidocaine, tetracaine, and epinephrine, and place it directly onto the wound for approximately 5 minutes.10 For rib fractures, use 700 mg lidocaine under a 10 × 14 cm occlusive dressing.

LOCAL ANESTHETIC INFILTRATION

Local anesthetic infiltration generally works well, even when administered by novices and those who do not use it regularly. This is because it diffuses through the tissues without the clinician needing to know the specific neuroanatomy.

The key to giving successful local infiltration (also for regional blocks) is to wait long enough for the anesthetic to take effect. There is a delay, a latent period, of up to 15 minutes between when the anesthetic is administered and when the area is anesthetized. (A good practice is to do the block, leave and do any paperwork associated with the case, and then return to do the procedure.) If pain—not pressure or touch sensation—still exists after 15 minutes, administer additional anesthetic. You can also give the patient mild sedation, such as an anxiolytic (a paramedication). The most common reason that local anesthesia and anesthetic blocks do not work is that the clinician does not wait long enough.

Infiltration anesthesia uses larger volumes of weaker anesthetics (e.g., 100 mL of 0.5% lidocaine). Regional blocks of larger nerves use smaller volumes of more concentrated anesthetics (e.g., 10 mL of 2% lidocaine). Table 15-1 shows how to mix 1% and 2% lidocaine with normal saline (NS) and epinephrine to produce various quantities of 0.5% lidocaine with 1:200,000 epinephrine.

| Desired Amount of Local Anesthetic | Normal Saline/ Lidocaine 2% | Normal Saline/ Lidocaine 1% | Add Epinephrine 1:1000 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 20 mL | 15 mL/5 mL | 10 mL/10 mL | 0.1 mL |

| 40 mL | 30 mL/10 mL | 20 mL/20 mL | 0.2 mL |

| 100 mL | 75 mL/25 mL | 50 mL/50 mL | 0.5 mL |

| 200 mL | 150 mL/50 mL | 100 mL/100 mL | 1.0 mL |

To maximize efficiency when large numbers of patients require procedures done under local anesthesia, group them together. Do not interpose cases under general anesthesia, because this will only slow patient flow. Block the next patient while the surgeon is scrubbing for the first patient.12 When you must do a series of very short procedures under local or regional anesthesia, you can often block several patients at once using a longer-acting anesthetic (often containing epinephrine 1:200,000).

If a patient tells you that he or she is allergic to a local anesthetic, avoid that class of medications (usually an ester). Anesthetics in the ester class do not have an “I” before “caine” in their name (e.g., procaine, cocaine). The names of anesthetics in the amino amide class have an “I” before “caine” (e.g., lidocaine/lignocaine, mepivacaine). If you can’t use an anesthetic from the class that the patient is not allergic to (or if the patient does not know the drug he or she is allergic to), use one of the alternative medications described in the next section.

Anesthetics come as percent concentrations, with 1% equaling 10 mg/mL or 1 g of anesthetic per 100 mL. To dilute a local anesthetic, add sterile injectable saline. For example, adding 1 mL of anesthetic to 1 mL of saline changes a 1% solution into a 0.5% solution. If 3 mL of saline were added, it would become a 0.25% solution. An easy way to calculate the dose in milligrams is to use the formula: Volume (mL) × Concentration (%) × 10 = Dose (mg).13

When medication is scarce, reduce the needed dose of anesthetic either by diluting the solution or, except for cocaine, by adding epinephrine (adrenaline). Vasoconstriction increases an anesthetic’s length of action. Except for cocaine, local anesthetics without epinephrine added are vasodilators. Do not add epinephrine to cocaine; it is unnecessary and dangerous.

Premixed lidocaine with epinephrine (adrenaline) may not be available. The epinephrine concentration in lidocaine may be expressed as 1:1000, 1:10,000, 1:100,000, or 1:200,000. This means that a

1:1000 solution epinephrine = 1 part epinephrine to 1000 parts solution = 1 g epinephrine in 1000 mL solution = 1000 mg epinephrine in 1000 mL solution = 1 mg/mL

1:10,000 solution epinephrine = 1 g epinephrine in 10,000 mL solution = 1000 mg epinephrine in 10,000 mL solution = 1 mg/10 mL, which can also be expressed as 100 mcg/mL.

1:100,000 concentration means 1 mg of epinephrine for every 100 mL anesthetic.

1:200,000 concentration means 1 mg of epinephrine for every 200 mL anesthetic.

If lidocaine premixed with epinephrine is not available, use the following method to determine the amount of epinephrine to add to the local anesthetic:

To make a 1:200,000 epinephrine-lidocaine solution, add 0.1 mL (0.1 mg) epinephrine 1:1000 to 20 mL of lidocaine. To do this, take 1 mL of epinephrine 1:1000 and dilute it to 10 mL with saline. Then take 1 mL of this mix, which is now 1 mL of 1:10,000 epinephrine, and add 19 mL lidocaine. The total solution is now 20 mL, and the original epinephrine has been diluted 200 times = 1:200,000 solution.14

The maximum safe dose of epinephrine = 4 mcg/kg. Therefore, the dose for an 80-kg man = 320 mcg = 64 mL of a 1:200,000 solution.

To reduce burning from most local anesthetics, add 1 mL sodium bicarbonate (1 mEq/mL) to every 10 mL of 1% lidocaine.15 While the traditional teaching is that local anesthetics are unreliable when used in the acidic environment of an abscess, reports suggest that a “double-buffered” solution of 2 mL of bicarbonate with 8 mL of lidocaine works well.16 Heating the anesthetic to body temperature also helps reduce pain.17

If standard local anesthetics are not available or if the patient claims to be allergic to local anesthetics, use one of the available alternatives. These include medications with antihistamine activity, bacteriostatic normal saline (NS) with benzyl alcohol, sterile water, local cold, and pressure.

Most injectable medications with antihistamine activity can be used as local anesthetics if diluted to a 0.05% solution with NS. None are as effective as standard local anesthetics, but they will certainly do if nothing else is available.18

Diphenhydramine hydrochloride (Benadryl) works for dermal, urological, and dental anesthesia. Because it is very soluble in water, prepare a 1% solution by diluting 1 mL of a standard 5% diphenhydramine solution for injection with 4 mL single-use NS solution for injection (without preservatives).15 It should not be used in concentrations >1%, because that may cause ulcerations or tissue necrosis. Its duration of action is less than that of lidocaine with epinephrine and, even if buffered, it is more painful than lidocaine. A 0.5% solution can also be used, but it is considerably less effective than 1% lidocaine. Complications include sedation (occasional), local erythema (common), persistent soreness lasting up to 3 days (common), and skin sloughing (rare).15,19 Dimenhydrinate (Dramamine) also has local anesthetic activity.18

Tripelennamine (aka Pyribenzamine [PBZ]), a highly water-soluble antihistamine, is effective for a wide variety of regional nerve blocks in a 1% solution. As clinically effective as diphenhydramine, tripelennamine has fewer and less severe side effects. It can be used for urethral anesthesia20 and, in a 4% solution, as a mucosal anesthetic on the gums. In powdered form, it immediately relieves toothaches in a decayed tooth. As a 1% solution, it has been used for topical anesthesia in the mouth and esophagus and, usually with epinephrine, for skin and dental block infiltration.21 The addition of epinephrine reduces local reactions and lengthens the anesthetic’s effect up to four times. For pain relief, use between 5 mL (lingual nerve block) and 20 mL (dorsal sympathetic nerve block). For surgery done with a tripelennamine nerve block, use between 10 mL (finger block) and 35 mL (tendon graft). The anesthetic effect is prolonged by adding 1:100,000 epinephrine.22

Phenothiazines (e.g., promethazine [Phenergan], chlorpromazine [Thorazine]) are 23 times more potent than procaine as a local anesthetic.23 Chlorpromazine is effective as a local anesthetic at concentrations of between 0.1% and 0.2%. It has a wide safety margin, but should not be used with epinephrine. Even without a vasoconstrictor, it has a longer duration of action than most local anesthetics. One complication, orthostatic hypotension, usually occurs when chlorpromazine is used IV or in large doses.24 Although it has significant local anesthetic properties, chlorpromazine has never been generally used as a local anesthetic in humans.23,24,25

Sterile water is a suitable anesthetic. Known to our predecessors as “aquapuncture,” this method uses unpreserved sterile water produced by simply boiling distilled water. As with other local anesthetic infiltration, injecting water works better on loose tissues and is less painful when the water is at body temperature and injected slowly. The analgesia lasts 10 to 15 minutes.26

Allen described the procedure he used: “To obtain the full analgesic effect, it is necessary to infiltrate the tissues to the point of producing a glassy edema, the skin or mucous membrane must be infiltrated intradermally and the infiltration carried down the full depth of the proposed incision; when this is done, analgesia is usually as profound as after infiltration with the weaker anesthetic solution, but tactility is little or not at all affected; the after-pain or discomfort is about the same as that following the use of other anesthetic solutions.”26

Benzyl alcohol, the preservative in bacteriostatic NS, is an ideal alternative local anesthetic. Inexpensive and readily available, bacteriostatic NS is frequently used to flush IV catheters and to dilute or reconstitute medications for parenteral use. Another formulation is to mix benzyl alcohol (0.9%) with 1:100,000 epinephrine by adding 0.2 mL epinephrine 1:1000 to a 20-mL vial of multidose NS solution containing benzyl alcohol 0.9%.15 This formulation is less painful, but slightly less effective, than 0.9% buffered lidocaine. In children, the pain on injection is about the same as that with lidocaine.27 Without epinephrine, the anesthetic effect of benzyl alcohol lasts only a few minutes; with epinephrine, anesthesia lasts about 20 minutes.28

Some antidepressants, such as amitriptyline, have shown good activity as both topical and injectable anesthetics. When the need is desperate, these can be used, although questions about their safety preclude their use under normal circumstances.29

Neither morphine nor meperidine (Demerol, Pethidine) works well as a local anesthetic. They have a potency about half that of chlorpromazine and slightly less than that of promethazine.25,30

Apply cold to tissues to produce either local or regional anesthesia. (See also “Refrigeration Anesthesia: Amputations” below in this chapter.)

Locally applied cold provides extremely short-acting superficial anesthesia for “stab” abscess drainages, venipunctures, injections, and similar procedures. If ice is used, it must be in direct contact with the skin for at least 10 seconds immediately before the procedure. The effect lasts only a few seconds.31

Cold sprays for local anesthesia were developed in the mid-19th century. Various substances with low boiling points can be used, including ether, and alcohol cooled to –23°C (–10°F).32

Ethyl chloride (chloroethane) spray effectively anesthetizes a very small area of intact skin for a few seconds—approximately enough time to do a stab incision for an abscess. It works by “freezing” the skin. Because of its potent and potentially dangerous general anesthetic effect with abuse potential, never use it on the mucosa. It is available commercially as a cleaner (e.g., for computer keyboards) and as a medical spray. This chemical is flammable and fires have occurred while using it with diathermy.33 Tetrafluoroethane spray, used to remove dust from personal computers, can serve as a handy substitute.34 (Don’t inhale it; you’ll pass out.)

Use an atomizer to spray ethyl chloride. Directions for two homemade atomizers are in Chapter 14. Hold the atomizer just far enough from the body part being anesthetized to maximize the amount of spray reaching the skin before dissipating. If held too far away, the spray evaporates without anesthetizing. Protect sensitive parts, such as the eyes and anus, before spraying the anesthetic on surrounding areas.

Direct pressure over an area produces transient anesthesia. As Allen wrote in 1918, “The benumbing effect of long-continued pressure upon any part of the body is well known; although some pain may be produced in the surrounding parts, it is possible to carry it to a point of depressing both tactile and painful impressions to a considerable degree; this is brought about in two ways, first the compression directly paralyzes the nerve-endings of the part, and, secondly, the anemia [actually, tissue hypoxia] intensifies this effect.”35

Inject the anesthetic slowly. This markedly diminishes the patient’s discomfort. Using buffered lidocaine also decreases pain, as described previously.

Use a simple field block for circumscribed lesions, such as cysts or small abscesses, and for larger structures, such as ears. Visualize a diamond surrounding the area to be anesthetized, and then inject two small wheals at the apex of the diamond (Fig. 15-1). Next, block the four sides of the diamond through those wheals.

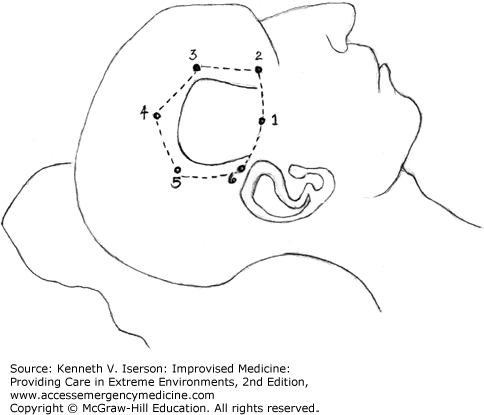

Local wound infiltration is effective for inguinal and umbilical hernia surgery, dental procedures, strabismus (eyes) surgery, and burr holes/craniotomies.36 For craniotomies, anesthetize the scalp surrounding the entire surgical area, as well as the underlying muscles and the periosteum (Fig. 15-2).37 Use the greatest possible anesthetic dose, because the scalp is so vascular. Always use anesthetic with epinephrine.

In situations where there is no alternative, almost any surgical procedure can be done by cutting through a site that has been locally infiltrated with anesthetic, with continued anesthetic injections given as the operation proceeds.

The Vishnevsky technique, an “inject-and-cut” procedure once employed extensively in Russia, is possibly the simplest use of local anesthetics, because no knowledge of anatomy is required. The technique works very well for surgery outside the abdomen and chest. Abdominal surgery is not quite as easy; it is simple enough to open the abdomen with this technique, but handling the viscera is a different matter. The technique is to inject unlimited volumes of weak procaine solutions (0.25% to 0.5%) without epinephrine. Procaine is the only completely safe anesthetic to use for this procedure, because it is metabolized very rapidly. Other local anesthetics are metabolized more slowly, and the patient can become toxic.38 If lidocaine is used, the limit is 200 mL of 0.25% lidocaine with adrenaline 1:500,000.

The primary danger of the Vishnevsky technique is inadvertent intravascular injection, which can be avoided by aspirating before injecting and keeping the needle moving.39

Premedicating patients may be useful when giving either regional or general anesthesia. It reduces patient anxiety and often lessens the amount of anesthetic that is needed. The drugs used for premedication, such as benzodiazepines, phenothiazines (especially the commonly used promethazine), and barbiturates, are commonly available. Administer them orally, parenterally, or rectally.40 Benzodiazepines and barbiturates have the added benefit of raising the seizure threshold.

Hypnosis, even if patients use a hypnosis recording, is effective as a premedication. The significant benefits of hypnosis include decreased anxiety, decreased blood pressure (BP), reduced blood loss, enhanced postoperative well-being, improved intestinal motility, shorter hospital stays, reduced postoperative nausea and vomiting, and a reduced need for analgesics.41 Hypnotic techniques are described below in this chapter.

If patients become anxious or experience pain during a regional block or the subsequent procedure, give them an analgesic or an anxiolytic as paramedication. Commonly available paramedications include mild sedatives, opioids, and ketamine.

REGIONAL BLOCKS

Regional blocks are more problematic for inexperienced practitioners than infiltration anesthesia. Nevertheless, simple nerve blocks are effective for a wide variety of procedures and operations. The blocks described here will usually provide good analgesia, even when the practitioner does them for the first time. Note that this book is not designed to describe the wide variety of regional blocks, even though they are remarkable tools when resources are scarce. Find descriptions of many of the blocks you may need at the New York School of Regional Anesthesia’s free website (www.nysora.com).

All the nerves to the forehead and scalp run upward from about the line of the eyebrow anteriorly and from the base of the skull posteriorly. Therefore, to block a region above this line you need only to inject a horizontal line of anesthesia through this area.42 The key is to make the anesthesia line long enough to block the cross innervation from nerves that are lateral to the site of injury. A good rule is to block both sides of the face or scalp for any lesion near the midline.

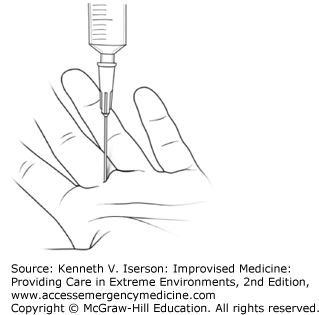

The traditional finger and toe blocks (ring or intermetacarpal) involve at least two injections. The SIMPLE (single subcutaneous injection in the midline of the proximal phalanx with lidocaine and epinephrine) block is easier, faster, and simultaneously conserves anesthetic and reduces patient discomfort.43 To do this block, inject about 2 to 3 mL lidocaine 1% with epinephrine 1:100,000 just above the tendon sheath at the midpoint of the crease where the finger joins the palm, on the volar (palmar) side (Fig. 15-3).44 The block works on fingers and toes at least as well as traditional blocks. It may not, however, work as well on the thumb.45

A hematoma block can provide sufficient analgesia in the distal forearm and some areas of the face, such as the nose, to reduce fractures. Useful in both adults and children, it is easier to perform but is less effective for forearm fractures than is an IV regional block (e.g., intravenous regional anesthesia [IVRA], Bier block).46 Nevertheless, if the necessary equipment or skilled personnel are unavailable to do IVRA, then a hematoma block offers a quick and easy method to obtain at least some, if not very good, anesthesia.

This block may be particularly useful in mass casualty situations, but it is not effective to treat fractures >24 hours old, because by then the hematoma has begun to organize.38

Palpate the fracture site and, under aseptic conditions, place the needle into the fracture hematoma. Aspirate to ensure that blood returns. Unlike other regional blocks, you want to aspirate blood before injecting to ensure that the needle is in, and that the anesthetic can diffuse through, the fracture hematoma. Then, very slowly inject 5 to 10 mL of 2% lidocaine without epinephrine. Buffered lidocaine may cause less pain than unbuffered solution.

The block should take effect in approximately 5 minutes. This technique, useful both in adults and children, is most successful when applied as soon as possible after injury, because clotted blood will limit the spread of the analgesic. Infection is not a hazard if sterile solutions and apparatus are used and adequate skin preparation employed.39 The US military has found it occasionally useful to use ultrasound to locate the hematoma and guide needle placement.

If anesthesia (other than hypnosis) is needed to reduce a shoulder dislocation, an easy technique is to inject 20 mL of 1% plain lidocaine into the joint.47,48 This must be done under aseptic conditions. The technique is remarkably simple, because the joint space is easily identified (it’s where the shoulder used to be) and accessible. However, multiple studies have demonstrated that this technique usually has a lower success rate than IV sedation.49

Intravenous regional anesthesia (IVRA) involves administering a local anesthetic into an upper or lower extremity while blocking arterial flow and venous return with an inflated cuff.50 Used for more than 100 years, the technique is successful in >95% of cases. The advantages of this block, especially in austere situations, are that it is easy to perform; is not dependent on anatomical knowledge; requires minimal personnel; avoids the potential side effects of general anesthesia and systemic sedation; provides rapid and complete anesthesia, muscle relaxation, and a bloodless field; and is very safe.51,52 Disadvantages include the limited duration of anesthesia (60 minutes), the relatively large dose of local anesthetic required, and the fact that it provides no postoperative analgesia.

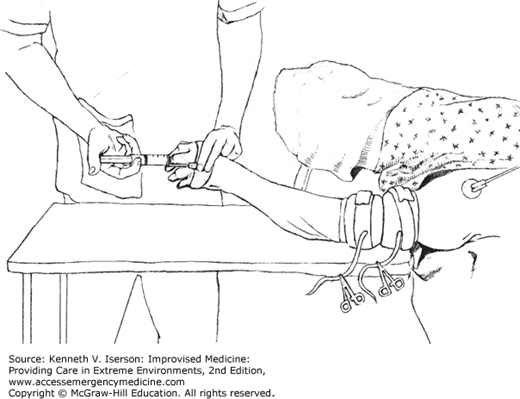

Place an IV line in the hand or the foot, depending on which extremity requires anesthesia. Place one or, preferably, two inflatable cuffs over padding on the proximal extremity, and secure them by wrapping them with strong adhesive tape so they do not accidentally come off when inflated. Then exsanguinate the extremity by lifting it straight up and wrapping it tightly, starting distally and moving proximally, with an Esmarch or other elastic bandage. If placement of an elastic bandage on the extremity is too painful due to trauma, compress the axillary or femoral artery for 5 minutes with the extremity elevated.

While the extremity is still elevated and wrapped, inflate the most proximal cuff to well above arterial pressure (palpated at the distal extremity) or, if there is an attached manometer, to 100 mm Hg above systolic BP and to at least 250 mm Hg. Use a hemostat to clamp the inflation tube on the cuff, because the valves tend to leak (Fig. 15-4).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree