Figure 22.1. Extent and duration of subarachnoid anesthesia with 40 mg lidocaine or 2-chloroprocaine in volunteers. (Adapted from Kouri ME, Kopacz DJ. Spinal 2-chloroprocaine: a comparison with lidocaine in volunteers. Anesth Analg 2004;98:75–80.)

3. Unilateral spinal block has also been advocated for outpatient procedures, particularly of the foot or knee. This requires maintaining the patient in a lateral position for 5 to 15 minutes to allow concentration of a hyperbaric solution in the dependent leg (13,14). This technique allows use of a lower dose of drug, but does not appear to provide faster recovery despite reduced pain and nausea in PACU. Its use may be limited to patients at high risk for nausea, and to where the block can be performed in an induction area.

4. Complications are the same in outpatients, but specific considerations may limit spinal anesthesia for outpatients.

a. Postspinal headache. The use of small round beveled needles has significantly reduced this complication, but it is still a potential, particularly in the younger patient group. Careful selection should be used, and the smallest diameter needle, consistent with easy performance of the block, should be used, usually 25 gauge or smaller. Patients must always be given appropriate contact information for follow-up in case symptoms develop. A mechanism for providing treatment should be in place.

b. Urinary retention is traditionally associated with spinal blockade, but usually with longer-duration blocks. Retention is also higher in older men, and perineal procedures such as hernia repair and anal surgery. Experience with short-acting spinal anesthesia (2-chloroprocaine, procaine, lidocaine, small dose bupivacaine) for low-risk surgery shows that the risk of urinary retention is no greater than that with general anesthesia (15).

c. TNS. This syndrome has occurred in association with every local anesthetic, and is particularly a concern in the outpatient because the onset usually occurs after discharge. Patients should be advised of the potential and assured that it is temporary, but a follow-up phone call is advisable to discover its occurrence and give reassurance to the patient if it occurs.

B. Epidural block. Spinal anesthesia is limited to a single-injection technique, requiring a single estimate of appropriate drug and dose to accommodate the surgical procedure, yet not to prolong discharge. In situations where surgical duration is unclear, epidural anesthesia, especially with a catheter, provides a reasonable alternative. Epidural injection is also less likely to produce a postdural puncture headache; however, it is technically more difficult to perform and requires more time, and the onset of blockade is longer.

1. Drug choices. Performance of epidural block aid in induction room with 2-chloroprocaine will provide adequate sensory anesthesia by the time the patient is moved to the operating room and surgical preparation and draping completed. The use of epidurals with 2-chloroprocaine for knee arthroscopy (16) or extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy (ESWL) (Figure 7.4 of Chapter 7) (17) is competitive with general anesthesia discharge times with propofol. Lidocaine may be acceptable for longer procedures, such as anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) repair, where a 60- to 90-minute duration can be anticipated. If longer duration is required, it is wiser to use a continuous technique with a short-duration drug and supplement as necessary. The resolution times required for mepivacaine or bupivacaine are unacceptable in most outpatient units.

2. Postoperative analgesia. With both epidural and spinal injections, block resolution (as required for discharge) is also associated with loss of any analgesic effect. Supplemental local anesthetic blockade of the incision performed by the surgeon should be encouraged, including local anesthetic in the joint in case of arthroscopy procedures (18). Supplemental peripheral nerve block of the extremities is useful (19). Patients should be treated with a multimodal analgesic regimen, which should include nonsteroidal analgesics (20,21), as well as small doses of oral opioids before discharge. Excessive opioids negate the advantages of avoiding nausea. Other nonopioids such as gabapentin, clonidine, and magnesium have been shown to be useful (see Chapter 23).

C. Combined spinal-epidural anesthesia has also been used in the outpatient, especially when rapid onset of sacral and lumbar anesthesia is needed, but the required duration is unclear. Specific examples include knee arthroscopy (22) and ESWL. A small dose of a short-acting drug can be used in this situation without anxiety of the procedure outlasting the anesthetic. Although this technique requires a somewhat longer time to place, it does provide the rapid onset that can overcome some of the objections to regional anesthesia for outpatients.

III. Peripheral nerve blockade

Unlike neuraxial techniques, peripheral blocks can be performed with long-acting drugs to provide both surgical anesthesia and prolonged analgesia even after discharge, and therefore, may help avoid the problems of nausea and vomiting associated with opioid analgesia. With a numb extremity, however, it is critical to provide ambulation aids for the patient and careful dressing of the involved extremity to avoid injury during the period of numbness, but this practice has been shown to be safe in several studies (23).

A. Upper extremity block

1. Shoulder surgeries are frequently performed on an outpatient basis. They are ideal candidates for regional anesthesia.

a. Interscalene blockade provides excellent anesthesia for the shoulder itself and is sufficient for simple shoulder arthroscopy, particularly if painful bone procedures are not involved. In those situations, a longer-acting local anesthetic or continuous catheter technique (see subsequent text) may be more appropriate. Performance of this block has been shown to reduce discharge time for outpatients, reduce postoperative pain and analgesic requirements, increase the frequency of phase 1 bypass, and reduce overnight admission (4,24–26). When the block is performed in an induction area, the surgical starting time is competitive with general anesthesia (4,27).

(1) Lidocaine or mepivacaine will give 6 to 8 hours of analgesia after an hour of surgical anesthesia.

(2) Bupivacaine 0.25% can provide 12 to 18 hours of analgesia, often sufficient to provide overnight pain relief for procedures such as rotator cuff repairs.

(3) Ropivacaine in 0.25% or 0.5% concentration will provide approximately 10 hours of analgesia in most patients (28).

b. If general anesthesia is chosen instead, a suprascapular nerve block provides some supplemental analgesia (1), but is not as effective as the interscalene (29).

2. Hand or upper arm surgery. Several techniques are available.

a. Intravenous regional anesthesia is an excellent choice for peripheral surgery if a tourniquet is to be used and the surgery is relatively minor (3, 30). The rapid return of function facilitates discharge and this technique has been shown to be less costly than general anesthesia (2,31). Lidocaine is an excellent choice, but provides little postoperative analgesia.

b. Supraclavicular block provides the simplest and most reliable blockade of the brachial plexus below the clavicle, but is avoided in most outpatient units because of the associated risk of pneumothorax. The use of ultrasound guidance may reduce this risk and restore the popularity of this block for outpatients.

c. Infraclavicular block has been used extensively, and, like interscalene, produces less pain, less analgesia requirements, more PACU bypass, and faster discharge (31), and (although it may require two injections) may be more comfortable for the patients than axillary blockade (32).

d. Axillary blockade remains the most popular in outpatient settings because of the minimal risk of pneumothorax (compared to more central blocks). It does require multiple injections, especially if the upper arm or forearm require anesthesia (see Chapter 12), but has rapid onset and provides earlier discharge than general anesthesia (33) and several hours of analgesia. Any of the many techniques described in Chapter 12 are useful.

B. Lower extremity blockade. Spinal and epidural anesthesia work well for the lower extremity, but do not provide analgesia as discussed in the preceding text. Peripheral nerve block requires more time, and generally several injections, but can provide excellent discharge analgesia.

1. Knee arthroscopy. Femoral nerve block supplemented with local injection of the portal sites can provide good operating conditions. A combined femoral (or lumbar plexus) and sciatic block is needed if total anesthesia is planned and postoperative analgesia is required. This technique provides faster discharge and more PACU bypass than general anesthesia (34). A supplemental obturator block may be needed for analgesia in some patients. With these blocks, loss of quadriceps function will occur, and patients will need to ambulate with crutches, as is often required after the surgery anyway.

2. ACL repair. For longer procedures, such as ACL repair, combined peripheral nerve blocks can be useful. In particular, a long-acting femoral nerve block provides comfort for 18 to 24 hours after surgery, especially if a patellar tendon graft is taken (35). If such blocks are placed in an induction room, the “anesthesia controlled time” in the operating room can actually be reduced compared to general anesthesia for the same procedure (5).

3. Foot Surgery. For surgery that is painful in the foot, block of the branches of the sciatic nerve in the popliteal fossa provides excellent anesthesia and analgesia, earlier discharge, and prolonged pain relief (36). A supplemental injection of the femoral branches along the medial side of the knee may be needed if the dorsum of the foot is involved. More proximal block is not needed and may limit ambulation.

C. Truncal procedures

1. Breast surgery can be performed with paravertebral blocks and light sedation. Again, the use of longer-acting local anesthetics will also provide prolonged analgesia and facilitate discharge. Patient satisfaction is good, but the potential complications of this application suggest it may not be the best choice for minor breast surgery (37) despite its advantages for larger operations.

2. Hernia repair is an ideal situation for regional techniques because of the significant postoperative discomfort. Neuraxial blockade supplemented by local infiltration by the surgeon works well (as does local anesthesia alone). Postoperative analgesia can also be provided by supplemental ilioinguinal and iliohypogastric blocks (38). Good operating conditions and analgesia are produced by paravertebral blocks, which can provide postoperative analgesia because they do not interfere with ambulation or discharge (39,40).

IV. Continuous catheter techniques

This is the area of greatest advance in the application of regional techniques. The use of catheters can provide 72 to 96 hours of analgesia after discharge and allows patients to avoid the frequent side effects of oral opioid analgesics after discharge (41). Experience with these catheters has been extensive in research centers (42). Complications are rare (43). In addition to superior analgesia and reduced side effects, catheter use provides great patient satisfaction (44) and improves return to daily function for outpatients after painful surgery (45).

A. Upper extremity

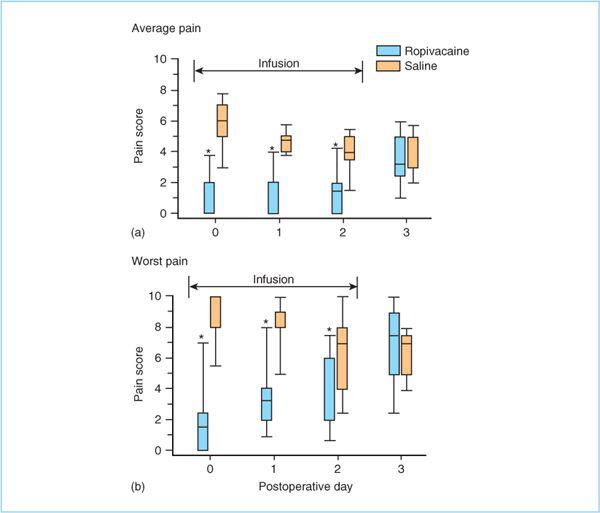

1. Painful shoulder surgery is well managed with continuous techniques. Interscalene catheters provide excellent pain relief for as long as 72 hours with lower visual analog scale (VAS) scores, decreased opioid consumption, and better sleep pattern (Figure 22.2) (46–48). The catheters are challenging to maintain because movement of the neck tends to dislodge the catheter. Secure dressings are important, and tunneling under the skin may be useful.

2. Infraclavicular catheters are useful for hand and upper arm surgeries. Again, they provide several days of improved analgesia compared to oral analgesics, with better sleep patterns (49), and may be easier to fix securely to the skin.

3. Axillary catheters have been placed, but are more difficult to maintain because of movement of the insertion site.

B. Lower extremity

1. Continuous femoral nerve catheters provide better pain relief than oral opioids or single injection techniques, and can maintain VAS scores and opioid consumption at significantly lower levels for several days (Figure 22.3) (50). A sciatic nerve catheter can be added for severe discomfort, but the dual catheters may produce an unwieldy and unmanageable extremity for most patients at home, and a single femoral infusion appears to provide adequate analgesia when supplemented with minimal oral analgesics, especially if a multimodal regimen is used.

2. Popliteal fossa catheters are appropriate for foot procedures and again provide significant improvement over oral analgesics alone (51–54). They can be inserted from the lateral approach, but may be easier to secure to the back of the leg using the posterior approach.

C. Management issues. The benefits of continuous catheters are impressive. Nevertheless, there is hesitation to use them because of additional time and equipment required as well as concern over potential and theoretical complications. They undeniably require more effort at follow-up and the provision of a 24-hour resource person for the patients managing these infusions at home. Experience has shown that the problems are infrequent and the equipment reliable (43).

Figure 22.2. Pain scores on a 0 to 10 visual analog scale (VAS) at home with 72-hour continuous interscalene infusion of ropivacaine compared to saline infusion after shoulder surgery. (Adapted from Ilfeld BM, Morey TE, Wright TW et al. Continuous interscalene brachial plexus block for postoperative pain control at home: a randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled study. Anesth Analg 2003;96:1089–1095.)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree